A Big Fracking Deal

A Fractured History

A thumbnail view of the history of extreme natural gas extraction in western Colorado and America, from nukes to fracking.

1969

The US Atomic Energy Commission detonates a 40-kiloton nuclear device 8,000 feet underground at Rulison, near the town of Rifle and the Colorado River, to liberate natural gas from shale. The gas is too radioactive and is flared off into the air for several years before the well is capped.1982

Exxon pulls the plug on multibillion-dollar oil shale project, leaving cavernous mines complete with machinery near the just-begun community of Battlement Mesa, Colorado, meant to be an oil town.2002

Texas starts fracking, and residents start suffering contaminated water, poor air quality, headaches, dizziness, blackouts, and muscle contractions. Many fracking toxins are known to attack the central nervous system. Children are especially vulnerable and become seriously ill in towns such as Argyle and Bartonville.2004

The EPA uses oil and gas industry-backed studies while failing to conduct its own and is pressured by the industry to conclude in a report that fracking isn’t necessarily always harmful. The industry consistently misrepresents the EPA’s position as approving fracking. Ben Grumbles, EPA assistant administrator at the time, has said, “We never construed it as a clean bill of health (for fracking).”2005

Though most drilling companies say they discontinue using diesel in fracking fluids this year, the EPA finds numerous instances of diesel still present in 2010.George Bush’s administration adds a clause to an energy bill exempting fracking and other drilling methods from the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act.

2007

A study near Parachute, Colorado, finds five wells contaminated with methane.2008

Garfield County, Colorado, outfitter Ned Prather is hospitalized after drinking water poisoned by chemicals seeping into his spring, which is surrounded by eighteen gas wells.New Mexico officials report more than 700 incidents in which contaminants from 400 O&G waste pits leaked into groundwater. Colorado regulators report more than 300 similar cases.

A Durango, Colorado, nurse nearly dies of organ failure after treating a rig worker who spilled fracking fluids on his clothing.

2009

Colorado passes regulations requiring companies to divulge fracking fluid contents—but only in cases of emergencies. No one, including those living closest to drilling rigs, can know what drillers are pumping into the ground unless something goes bad. Regulation is essentially voluntary, relying on a discredited FracFocus website started by the O&G industry that lists all chemicals used at various sites as reported by drillers.In Caddo Parrish, Louisiana, sixteen cows die after drinking fracking fluids from puddles in the fields. Similar deaths include seventy cows in Pennsylvania exposed to fracking wastewater and another herd where pregnant cows had a 50 percent rate of stillborn calves after grazing in fracking-chemical-polluted pasture.

In Pavillion, Wyoming, after seven years of complaints, the EPA conducts a study that finds contamination from hydrocarbons and associated chemicals in nearly one-third of water samples.

2010

An EPA update of fracking effects on drinking water is announced with a 2012 completion date. In 2012 the EPA issues a 278-page progress report and bumps the study’s projected finish date back to 2014.Earthquake swarms and a couple of bigger quakes in Arkansas are tied to drilling activity in the Fayetteville Shale. A US Geological Survey research team says the spike in earthquakes since 2001 near O&G extraction operations is “almost certainly man-made,” citing injection of drilling wastewater as a possible cause.

2011

State regulators confirm hydrogen sulfide is detected at levels up to 450 parts per million (ppm) at four well pads south of Parachute; 100 ppm can produce coughing, eye irritation, and loss of smell after fifteen minutes. Exposure at that level for several hours can result in death. Over 500 ppm is lethal.A US Forest Service analysis notes that the cumulative impact of gas well emissions could mean “substantial adverse air quality effects” on nearby wilderness areas.

The Maroon Bells–Snowmass Wilderness could see ninety-eight days a year with unacceptable visibility.Of 632 chemicals used in natural gas production, a study finds 75 percent can affect the skin, eyes, other sensory organs, and respiratory and gastrointestinal systems; 40 to 50 percent can affect the brain/nervous, immune, and cardiovascular systems, and kidneys; 37 percent can affect the endocrine system; and 25 percent can cause cancer and mutations.

An MIT study, headed by an industry insider, concludes, “With 20,000 shale wells drilled in the last ten years, the environmental record of shale-gas development is for the most part a good one.” But the actual numbers of human-health problems and water-contamination issues are still high. And MIT determines in a subsequent study that large global supplies of shale oil being made accessible are having negative impact on R&D for renewable energy sources that move consumption away from greenhouse-gas emitters.

Fracking is banned, or at least temporarily suspended, in France, Switzerland, Bulgaria, and other countries.

2012

The Federal FRAC Act, introduced by Colorado congresswoman Diana DeGette, attempts to have fracking once again considered under the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act but bogs down in committee. DeGette plans to reintroduce the act in 2013.Duke University researchers in a peer-reviewed study find that the closer a water well is to a gas well in Pennsylvania, the more likely the water will be to contain methane.

Cornell University researchers release a peer-reviewed paper connecting fracking and animal deaths, from livestock to pets, in six states, saying true numbers are unknowable as a result of no reliable testing, less than full industry disclosure about fracking fluid contents, and “industry’s use of nondisclosure agreements.” The latter pertains to O&G settlements for animal deaths.

A US District Court judge in Colorado denies a proposed settlement between the DOJ Antitrust Division, Gunnison Energy, and SG Interests for colluding in federal mineral leases bidding. The $550,000 total fine is deemed by the judge not to be a “realistic deterrent.” The amount has been upped to $1 million but has not yet been accepted by the judge.

2013

The Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission adopts new rules increasing well setbacks from 150 feet (in rural areas) and 350 feet (in urban areas) to a minimum of 500 feet, with room for exceptions. Fracking drillers are also required to test groundwater before and after drilling, making Colorado the first state to require sampling after drilling.A controversial EPA announcement dramatically lowers previous estimates of how much methane leaks during natural gas production. The EPA says companies reduced them with better gaskets, maintenance, and monitoring in order to improve their own bottom lines.

The latest National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data indicates substantial methane is still leaking around the gas pads and wells surveyed. Cornell University professor Robert Howarth, who conducted a more dire 2011 methane leak study, notes that the EPA “seems to be ignoring the published NOAA data, and the bias on industry only pushing estimates downward—never up—is quite real.” Howarth believes the EPA “badly needs a counteracting force, such as outside independent review of their process.”

A 2008 fracking moratorium in New York state is extended to 2015.

Mora County, New Mexico, becomes the first county in the US to ban all O&G drilling. Neighboring San Miguel County has a temporary moratorium in place. Pitkin County is not allowed to do either by state statute, “or we certainly would,” says Pitkin County Commissioner Michael Owsley.

The Obama administration announces that companies drilling on federal lands must

disclose fracking chemicals. Environmental groups call the position weak.

The middle of an active gas field is like a cross between a TV ad for energy independence and a sci-fi movie about a mining colony in Mordor. Roads, pipelines, and machinery snake everywhere in a proud display of American ingenuity and development. But the roar of the fracking—a controversial form of natural gas extraction—can feel like a continual earthquake. Dusty air is bent by wavy methane emissions, while big drilling rigs and flared toxic gases give the process the look and blinding odor of an oil refinery.

Unlike refineries, however, gas fields are often close to rural residences or in the middle of otherwise unpolluted open country where people farm and ranch, climb and hike, hunt and fish, ski and snowshoe. Places such as Thompson Divide, thirty miles from Aspen, where plans are in place to subject the land to gas-well development that will include fracking.

Most of the 220,000 federal acres that make up the Thompson Divide are remote, roadless, and difficult to access. Approximately 88,000 of them are in Pitkin County. They roll out in a beautiful swath of mountains, dark timber, and creeks, between Coal Basin to the west of Redstone all the way to Sunlight ski area south of Glenwood Springs and on toward Grand Mesa in the west.

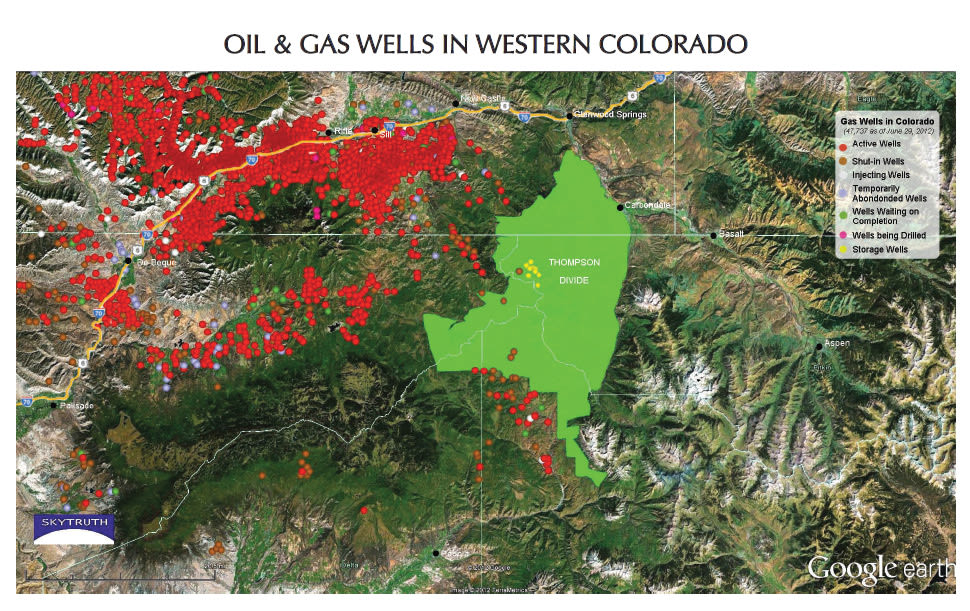

Oil and gas wells dot the landscape north of Parachute, Colorado, a visual yardstick of what the Thompson Divide area could become if oil and gas companies move forward there.

Image: Daniel Bayer

The streams and aquifers of the area are the water sources for numerous nearby ranches and farms that raise cattle and other livestock and grow fruits and vegetables. Some of this bounty ends up on tables in the Roaring Fork Valley. If the water that makes the agriculture possible becomes toxic or is otherwise negatively impacted, the repercussions will be both far- and near-reaching.

Beyond the groundwater issues, air pollution results from venting methane and other toxins, as well as from the serious amounts of dust that drilling generates. Air-quality degradation in formerly blue-skied locales such as Wyoming’s Pinedale region is well documented. Similar problems can be seen around Parachute, Silt, and Rifle to the west of Aspen.

Thompson Divide is even closer to the Roaring Fork Valley and directly upwind. A US Forest Service review found that the current drilling in Colorado, even absent drilling in TD, can produce up to ninety-eight days of unacceptable visibility in the Maroon Bells–Snowmass Wilderness, the backbone of the region’s uncompromised beauty.

The Bureau of Land Management oversees a quarter of a billion acres of federal land nationwide. In the West’s five biggest oil- and gas-producing states—Colorado, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico—42 percent of BLM land is already leased for oil and gas (O&G) extraction. That includes 105,000 acres of Thompson Divide. In the past several years, the companies holding some of those leases have been pursuing drilling more than 100 new wells. While a handful of wells have already been drilled within the TD boundary, including some that date back to the 1940s, it is the new wells that are of major concern.

Concerned citizens fill a room in Carbondale’s Third Street Center to discuss gas drilling in Thompson Divide.

Image: Daniel Bayer

The leases for some of those wells were set to expire this year. Though renewals are usually pro forma, because of intense public pressure the BLM announced it would take public comments, hold hearings, and issue a decision about the matter by this past May. The agency was overwhelmed with input. A town hall meeting in Carbondale in March was so well attended that many people had to stand outside in the cold waiting to be heard. In an almost Hollywood-style display of public outcry, everyone from high school students to octogenarian ranchers stood up to voice their protests, reflecting a community from Aspen to Glenwood Springs that was overwhelmingly—and, for this valley, unusually—united. And it was nearly all in opposition to drilling in the Thompson Divide.

Aaron Kindle of Trout Unlimited, a fifty-year-old national nonprofit focused on fishery protection, took the microphone and called the TD area “very likely the most pristine landscape slated for energy development in Colorado and perhaps the West. It is ecologically rich and provides a pivotal link between the protected high country of the Maroon Bells–Snowmass Wilderness and the lower-elevation country of the Grand and Battlement Mesas.”

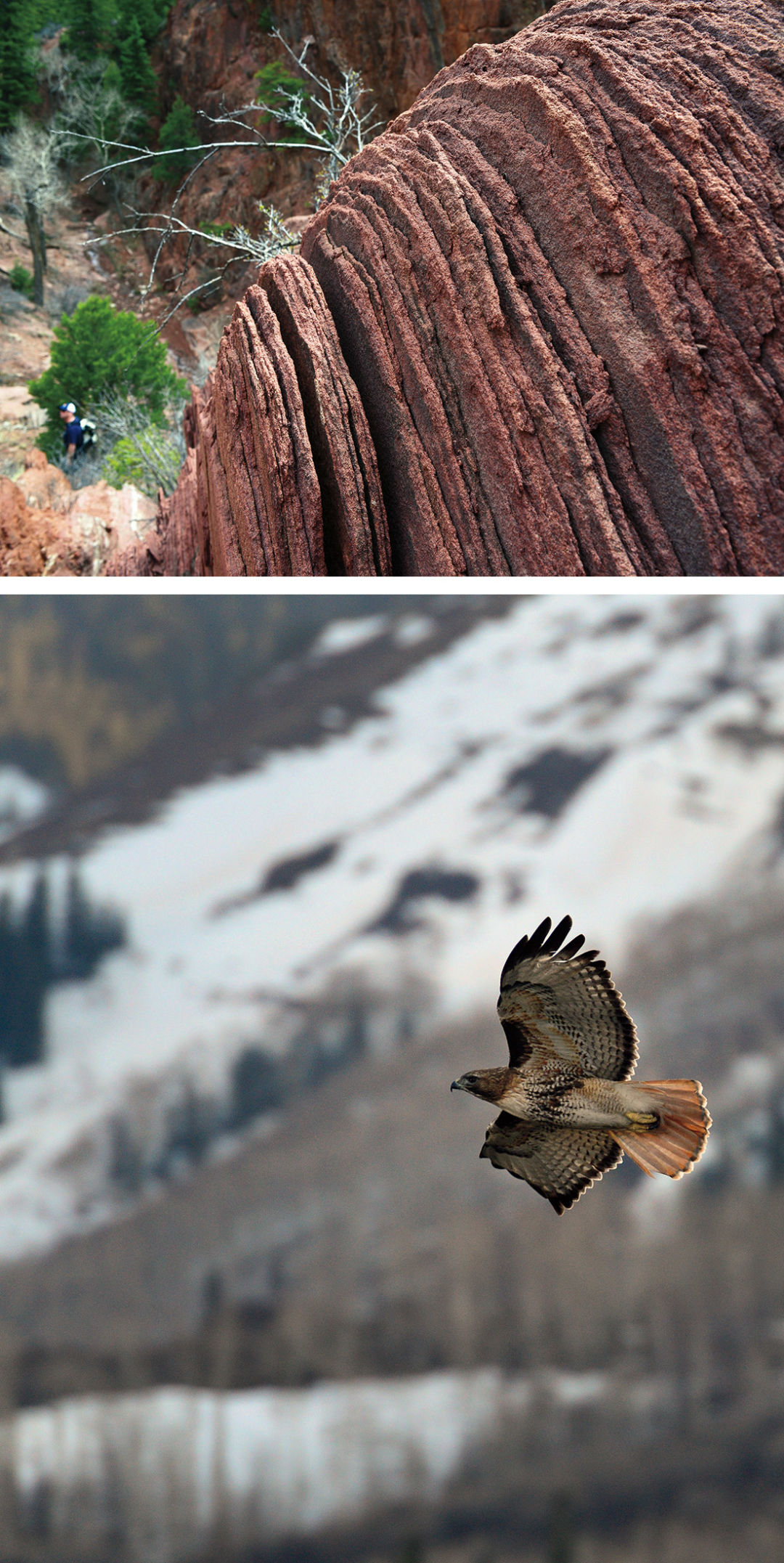

“Numerous wildlife species rely on the area,” Kindle continued. “Elk and deer . . . for critical life stages such as calving and breeding and for summer range. Colorado Parks and Wildlife has even called it an elk factory. The habitat this area provides makes the Thompson Divide a hunter’s paradise. . . . Unit 43, for instance, is one of the top fifteen most hunted units in all of Colorado.”

Last year, 14,000 hunting licenses were issued in the area, the money from which funds a lot of work in support of wildlife across the state. Research conducted by the Thompson Divide Coalition (a nonprofit opposed to O&G development in the area) has shown that hunting, fishing, and recreation in TD generates more than 1,000 jobs in the counties involved and close to $100 million annually in direct and ancillary revenues. And there’s ample evidence throughout the West that mule deer, elk, pronghorn, and sage grouse numbers all plummet where wholesale fracking is being done.

The two drivers of the Thompson Divide “play” (as the industry refers to new developments) are Gunnison Energy, owned by billionaire local ranch owner and mega-political-donor Bill Koch’s Ursa Resources of Houston, and SG Interests, owned by another billionaire local ranch owner, Russell Gordy.

The companies can clearly afford to go the distance on projects they commit to. They can also afford the million-dollar fine levied this April in a settlement with the US Department of Justice’s antitrust division for joint-bidding collusion on leases. Both companies are also said to be under federal investigation for price gouging along pipelines they co-own in the area. Other legal appeals have called the legitimacy of their original leases into question, because they weren’t properly awarded. Nevertheless, the BLM granted one-year extensions on the leases in question.

Dorothea Farris, a former Pitkin County commissioner and a board member of the Thompson Divide Coalition, saw the decision as a reason for optimism. “The BLM has given the gas companies a year to do what they didn’t do before they got the leases, and that is make a NEPA [National Environmental Policy Act] study,” she says. “With the Forest Service that usually takes four years. We’ll see if they can get it done in one. I don’t see how they can. I think it was the best solution, because it kept us out of the lawsuits that would have resulted if BLM had just declined to renew the leases. Then everyone would have gotten sued. This was all the BLM could do. I think it’s a victory. Others don’t.”

The sea of red dots indicates many active gas wells to Aspen’s west.

Image: Daniel Bayer

Questions remain. Will the companies be able to complete NEPA studies in a year? If not, will they request further extensions or consider litigation? Neither company has said, nor has the BLM speculated on whether it will grant more extensions.

Rampant drilling for natural gas has been controversial in the West, including the western slope of Colorado, for more than a decade. I’ve been around energy exploration for much of my life, having grown up in Wyoming and Colorado and spent significant time in Montana and Texas. In 1969, the earth rippled under my feet near Rulison, Colorado, just sixty-five miles from Aspen, when an underground nuclear device was detonated in an attempt to liberate natural gas from shale. I reported on the subject for this magazine in a 2006 piece called “Shale Shocked,” which looked at some of the history surrounding extreme oil-shale development in western Colorado. It also discussed the new trend of fracking.

Since that time, the pace of natural gas extraction has accelerated tremendously here in Colorado and around the country. The O&G industry is facing opposition from environmentalists and others who fear fracking’s serious impacts yet, ironically, is also supported by environmentalists and others who embrace natural gas’s lower greenhouse gas emissions in comparison to those of other fossil fuels. Many people feel that when the choice is between so-called clean coal and allegedly “green” natural gas (both of which western Colorado has lots of), it’s a little like being asked if you’d rather be hit by a train or a truck.

A big reason for that is because of fracking and the advances in horizontal-drilling techniques. Traditional oil and gas drilling over the last hundred-plus years hasn’t been problem free. But it has never engendered the amount of concern that the new methods have.

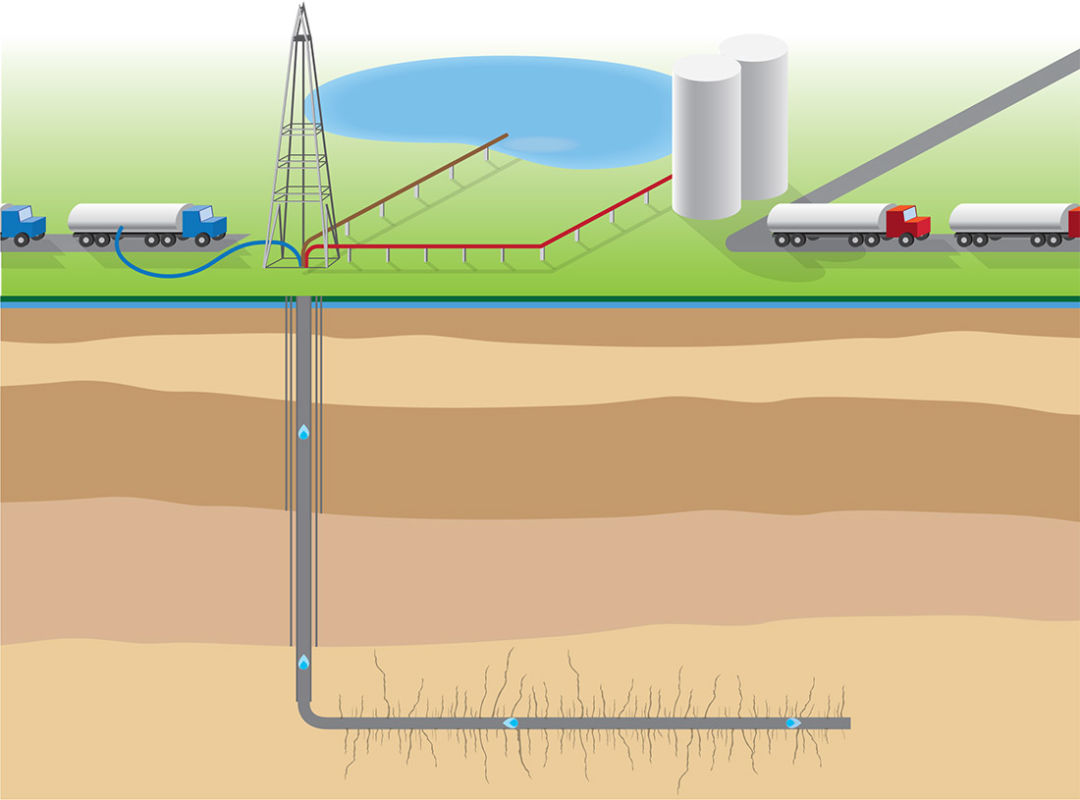

Image: Daniel Bayer

Fracking uses millions of gallons of mostly trucked-in water mixed with sand and potent chemicals that are injected at high pressure into a gas well to fracture targeted sandstone, limestone, and shale formations to create pathways for entrapped natural gas to migrate into a pipeline. The sand keeps the fissures open, while the fracking fluid acts like K-Y Jelly to lubricate everything and facilitate the flow of gas. Not only are millions of gallons of freshwater used in fracking each well, but the wastewater pumped back out is polluted and has to be dumped into other deep well sites, where it can present further problems.

The fracking process, which can last for months on each well, is so crazed, with its invasion-style truck traffic, high-volume industrialized chuffing of chemical-laced water, and gas flares turning night into day, you might think it’s half high tech and half voodoo. And you’d be right. Because so far no one really understands all of its implications.

The O&G industry has had its eyes on oil shale in one form or another for nearly a century, because large formations of it in America have been estimated to hold trillions of cubic feet of gas. Various radical projects, including nuclear explosives, in-situ mining, and super-heated metal rods, have been attempted over the years with what critics characterize as weak regulations with little enforcement, seemingly because any negative consequences would be considered minor in the remote regions of the West that were being treated like one big crash-test dummy.

No approaches have shown more profitable results than fracking and the use of new lateral-drilling techniques that make deep, horizontal shale deposits much easier to fully exploit. This deeper horizontal drilling requires substantially more water and fracking fluids than traditional and shallower vertical wells.

The exact contents of most O&G companies’ fluids have until recently been considered proprietary, but they have been known to contain diesel and other hydrocarbons, toxins, and carcinogens. Some of those substances remain in the ground during drilling, and others are brought back up in wastewater that can leak at the rigs due to poorly contained wells. The contaminated wastewater is then trucked away and injected into deep well sites that are often unmonitored.

To the people living in gaslands all over the country, including thousands within seventy-five miles of Aspen as the fallout flies, having an often experimental, barely regulated industry operating in their backyard has become the new normal. And there is mounting evidence it’s coming with a heavy price.

The flip side is that the industry’s success at extracting gas with the new methods has made it possible to foresee stable natural gas prices in the US at or below recent levels of $4 per million BTUs, compared to a high in 2005 of $13. Current European and Asian spot prices are around $10 and $15, respectively.

America, according to the Department of Energy, is now estimated to have a 100-year supply of natural gas. The massive Marcellus Formation underlying New York, Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania is the largest known reservoir of natural gas in the country, with as much as 500 trillion cubic feet—enough to supply the entire country’s energy needs for two years. Another twenty-one trillion cubic feet underlies Colorado’s Piceance Basin, which includes Thompson Divide. Along with huge fields in the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and Texas, it all adds up. In total, thirty-two states may now have accessible gas fields.

In fact, America is so flush with the stuff that companies have recently been granted licenses to export it. Thus Piceance Basin gas from Thompson Divide could end up in Asia fetching $15 to $16 instead of the $4 it does at home. As industry observers have noted, the US will sell to Asia until Asia starts producing natural gas more cheaply, and then the US will buy it from there. With China announcing the opening of up to twenty major new gas fields, that may happen soon.

The use of fracking, pioneered in the late 1940s by Halliburton, has been hailed by some as one of mankind’s greatest inventions of the past hundred years. Anything that offers an opportunity to rewrite the energy balance sheets around the world by making natural gas more widely available is indeed major. Yet fracked gas wells generate potential problems at every stage of their existence.

Heavy truck traffic hauling in water and hauling out wastewater makes formerly quiet rural dirt roads unsafe and raises unhealthy volumes of dust. The initial fracking is so loud and continuous, cranked out by ten or more trucks at a time, many with 1,000-horsepower motors, that it can cause debilitating migraines and worse for nearby homeowners, while also generating toxic, nausea-inducing smells. The flaring of gas at the wellheads, which can go on for months, lights the scene up like an airport and sounds like jets taking off constantly at close range, while releasing dangerously high levels of benzene, toluene, and xylene, all known carcinogens, into the air. Even when a well is essentially finished, loud, leaky work-over rigs can be brought in to extract the last drops.

The biggest issues with fracking involve fundamental concerns about air and water contamination. Much of this starts with drilling in inappropriate sites: near schools and residential areas, in critical wildlife habitat, and in geologically unsound formations, where migration of poisonous fluids can be more likely to occur and needs to be closely monitored, but often isn’t. Widespread complaints about fracking have been voiced since the turn of the millennium but have rarely been investigated by the EPA.

Contamination can occur in several ways, including venting around well pads, poor containment of toxic wastewater sites, flaring, and blowups resulting in well fires. Inadequate drill casings to keep the wells from leaking and to contain the pollutants and toxins are significant problems. (The massive offshore leak in the Gulf of Mexico from the Deepwater Horizon, while not a fracking operation, resulted in part from casings giving out. Similar ruptures underground can be much harder to detect.) Former gas field workers have testified to the haste with which the casings are often installed and cemented and to the fact that as many as 30 percent of dryland rigs suffer “circulation disruptions,” which essentially means leaks.

Thompson Divide’s unspoiled beauty motivates its defenders.

Image: Daniel Bayer

On top of all the carcinogens and endocrine-attacking toxins used in the fracking process, a few years ago geochemist Tracy Bank in New York began to look at how the process dislodges naturally occurring radioactive materials in shale such as uranium, barium, zinc, arsenic, and chromium. Once loosed, these materials can attach to hydrocarbons and get sucked back to the surface with the fracking wastewater. The Marcellus Formation is known to be radioactive. And according to a 2011 study by the New York Times, water-treatment plants processing fracking wastewater have discharged radioactive content into public water supplies.

In addition, seismic activity possibly related to drilling and wastewater disposal in deep wells has been observed in a number of places, including Arkansas and normally quakeproof Texas. Researchers at the Seismological Society of America’s annual meeting in 2012 presented findings suggesting that ongoing earthquake swarms in the Raton Basin of New Mexico and Colorado, including Colorado’s biggest shake since 1967, are related to underground wastewater injection from coalbed methane drilling that produces many of the same wastewater problems as fracking.

Locally, West Divide Creek, near Silt, in Garfield County, was so polluted by methane and benzene in 2004 that residents were lighting the water on fire. The oil companies involved ultimately paid $372,000 in restitution.

For my story in 2006, I interviewed several people who were experiencing a variety of health problems, and they knew many others who were, too. One woman told me, “They started drilling next door in September of 2004, and I got a cold that didn’t go away all winter. My husband has a persistent cough; I have sinus infections. I got a big blast of gas odor in the face one day, and it gave me a headache in three seconds that never really went away.”

For years in Colorado and nationwide, O&G companies have been buying out property owners with contaminated water supplies and paying for cleanups of rivers and streams. Typically, these settlements carry no admission of guilt and come with gag orders. Like many others, two families I spoke to in 2006—which include the aforementioned woman, who at that time talked freely and unfavorably about fracking—were ultimately bought out and restrained from commenting.

I recently spoke to Dee Hoffmeister, who lives in Dry Hollow Creek near Silt, where some of the heaviest drilling has taken place. She has appeared in two documentaries, Split Estate and Gasland, talking about the effects on her health. “I get so sick I can’t stand up,” she says, “and I’ve had to leave for months at a time. My husband checks the air for me every day. If the trucks start coming by—a dozen or more at a time—I have to go inside or get really sick.”

Image: Daniel Bayer

A health study ordered by Garfield County commissioners in 2010 about the effects of gas drilling in Battlement Mesa found bad air toxins around the gas wells there and sick kids nearby. Air monitors throughout the county found fairly low levels of airborne chemicals, but there were notable spikes near wells. The study was abandoned in 2012 after it cautioned that gas drilling in Garfield County could have negative health impacts on nearby residents. Critics said it was because the gas-happy county commissioners and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) didn’t agree with the Colorado School of Public Health, which conducted the study.

Garfield County O&G liaison Kirby Wynn, who is employed by the county, told me, “The commissioners pulled the plug by general agreement with all parties at the second-stage level [in other words, prior to the final in-depth study and conclusion] and said, ‘Let’s put out everything we’ve got, a massive document, and call it at that, because we aren’t going to get any further with it, and we’re never going to get a consensus.’”

In the spring of 2013, Garfield County commissioners announced an important new study by Colorado State University that would take air readings at a number of well pads, something not previously done in the area. Garfield County will pay for $1 million of the $1.8 million project from the mitigation fund that the O&G industry pays into. The rest is coming from O&G companies Ursa, Encana, WPX Energy, and Bill Barrett Corporation, all big players in the county.

Needless to say, going from a Colorado School of Public Health study about real-world health impacts of fracking to an essentially industry-sponsored study of well-pad emissions has struck some as going backwards. But it’s a typical trend nationally, where numerous studies promised by the EPA and others have become delayed, stalled in committees, or had their funding dropped. (Examples cited in the “A Fractured History” timeline that accompanies this story include a long-overdue EPA update of fracking effects on drinking water and the slow death of the FRAC Act.)

In December 2012, a gas spill spouted from a Williams Company subsidiary pipeline near Battlement Mesa. No one discovered it for a month or reported it for three. The spill created a long hydrocarbon plume in Parachute Creek and has been the object of an ongoing cleanup, because benzene has been detected around, under, and in the creek at levels up to 18,000 parts per billion. Some fear it could end up in drinking and irrigation water—the allowable drinking water limit is 5 ppb—though local health officials disagree.

The CDPHE, which assumed oversight of the spill, decided in May not to fine Williams, but says the agency still may. This didn’t surprise local critics such as Leslie Robinson, the chair of the Grand Valley Citizens Alliance, a community organization established in 1997 to provide information about dealing with oil and gas drilling, who contends that the CDPHE and the oil and gas commission usually look out for industry over the public.

When I ask her about improvements in the drilling processes she acknowledges they’re getting better. “All of the companies except for the wildcatters [independents operating without a lot of financial resources] now want to go to closed-loop systems for the wastewater, because it’s to their advantage.”

Closed-loop systems are wells that keep the wastewater contained, and companies with pipelines can ship wastewater for reprocessing. “But that’s where the biggest problem is now is the pipelines,” says Robinson. “No one really has any overall oversight for them. The government is pretty lax on oversight in general.”

Given that, and because up-to-date, peer-reviewed, irrefutable long-term health studies in the gaslands remain rare, O&G companies have a convenient opening to claim they’re clean. The reasons for the paucity of on-the-ground intel are multiple. Fear of discouraging O&G business by overregulation is a big factor. The industry is supplying more new jobs in the country than any other single source. That’s a key issue in the electoral battleground states of Ohio and Pennsylvania and even Colorado. No reelection-hungry politician wants to cross an industry that’s powering local economies.

For those reasons and others, even fracking’s most fervent opponents concede that the technique isn’t going away. So the big question is: can enforceable best practices be applied that adequately protect water and air and don’t ruinously jack up drilling expenses?

The question has been posed for years, and the short answer is that the extraction process can definitely be improved. The O&G industry initially sued Colorado over the state’s updated drilling regulations in 2009, but the suit was dropped in 2011 after the industry discovered that being safer and cleaner didn’t impede drilling or hurt the bottom line.

Some drilling rigs today aren’t just better for the environment, they’re cheaper, safer, and more productive. Italian-made DrillMec SPA, for example, builds quieter fracking rigs that use closed-loop technology to eliminate wastewater pit issues while also managing to cut costs. In Texas, a company called GasFrac has tested new technology that replaces water-based fracturing fluid with a liquefied petroleum gel that turns back into gas underground. It can be extracted with the natural gas, resulting in a nearly complete recovery of fracking fluid.

Though the gas drillers claim they’re cleaning things up, it isn’t noticeable everywhere. “Nothing’s changed in our area,” says Hoffmeister. “They still use misting [spraying wastewater into the air to evaporate it] to disperse some of the water. And they’re still taking millions of gallons from our creeks and rivers to frack with, then ruining it and pumping it back into the ground.” Two of Hoffmeister’s neighbors had untreatable tumors they blamed on toxins from fracking. One has died; the other is terminal.

Thus the debate over the Thompson Divide has an epic backdrop. From Silt to Sydney, fracking is wreaking havoc around the globe. Australia is grappling with a massive drilling boom; France, Bulgaria, and Switzerland have completely banned fracking; and New York state has put it on indefinite hold.

The truth is that as all the collateral costs and damages are considered, natural gas is starting to look less attractive. While gas has been considered less environmentally damaging than coal because it has less greenhouse gas emissions, when all of the environmental impacts are included, it is difficult to determine which one is greener. In a recent study, Cornell University gave the nod to coal.

That’s partly because the health concerns surrounding fracking are no longer just rural problems confined to a few sacrificial hillbillies and goats. Consider two examples: The Colorado River, a major western artery for recreation, drinking water, and the irrigation of places like California’s Imperial Valley, could be at risk. And so could the drinking water for seventeen million people in Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and New York. No one knows what’s really going on in either case, and someone certainly should.

What’s needed is more legitimate, untainted studies—and they were needed yesterday. But, ultimately, the world’s endless energy consumption is, like any other drug, a very costly addiction, and cheap short-term fixes like fracking can be fatally unhealthy. If the trade-off is a willingness to hock the country’s water and air—or to sell them outright—for the temporary satisfaction of long-term energy binging, then the world may be too strung out to save the Thompson Divide. Or anyplace else.