Avant-Garde Aspen

THE BEGINNING

GOETHE BICENTENNIAL

Aspen’s cultural big bang paved the way for decades of artistic open-mindedness.

Between June 27 and July 16, 1949, on the grounds of what is now that the Aspen Institute, two thousand visitors embarked on a remarkable two-week cultural journey known then and now as the Goethe Bicentennial Convocation and Music Festival. At the time, the idea of a conference celebrating an eighteenth-century German poet or a festival of classical music was hardly avant-garde. Nevertheless, it was an event that planted the seeds of what would become a remarkably fertile period in the history of the visual arts in Aspen. Not only did it directly lead to the formation of what we now know as the Aspen Institute and the Aspen Music Festival and School, the events of the Goethe Bicentennial also paved the way for a host of adventurous, experimental, and, yes, even avant-garde undertakings in the years that followed.

The Goethe Bicentennial was the brainchild of successful Chicago businessman Walter Paepcke, chairman of the board of the Container Corporation of America, and Robert M. Hutchins, president of the University of Chicago. Their goal was to help mend cultural relations “between the Teutonic peoples and the rest of the world” in the wake of the Second World War. They aimed to accomplish this, or at least to get the ball rolling, by inviting leading humanists and intellectuals to Aspen for an international festival commemorating the bicentennial of the birth of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, deemed an appropriate avatar for the reunification of Western culture due to the perceived harmoniousness of his thought and the universality of his interests.

With such luminary speakers as theologian-philosopher-physician Albert Schweitzer (pictured on the previous page with the Paepckes) and Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, and musical performances by pianist Arthur Rubenstein, the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, and others, the festival was an enormous success. As University of Wisconsin professor Heinrich Henel recalled shortly afterward, “It has been a stroke of genius to choose this almost inaccessible mountain resort as the meeting place. Only in its seclusion was it possible for the transient audience to become a community in a few short days; and this sense of belonging together encouraged a liveliness of discussion and a spontaneity of effort rarely found elsewhere.” And indeed, Paepcke’s “stroke of genius” would have a long afterlife. Starting in the early 1950s, but especially in the second half of the 1960s, Aspen achieved deserved renown as a creatively wide-open place where seemingly anything was possible.

PHOTOGRAPHY

FROM THE FIRST PHOTOGRAPHIC CONFERENCE TO THE CENTER OF THE EYE

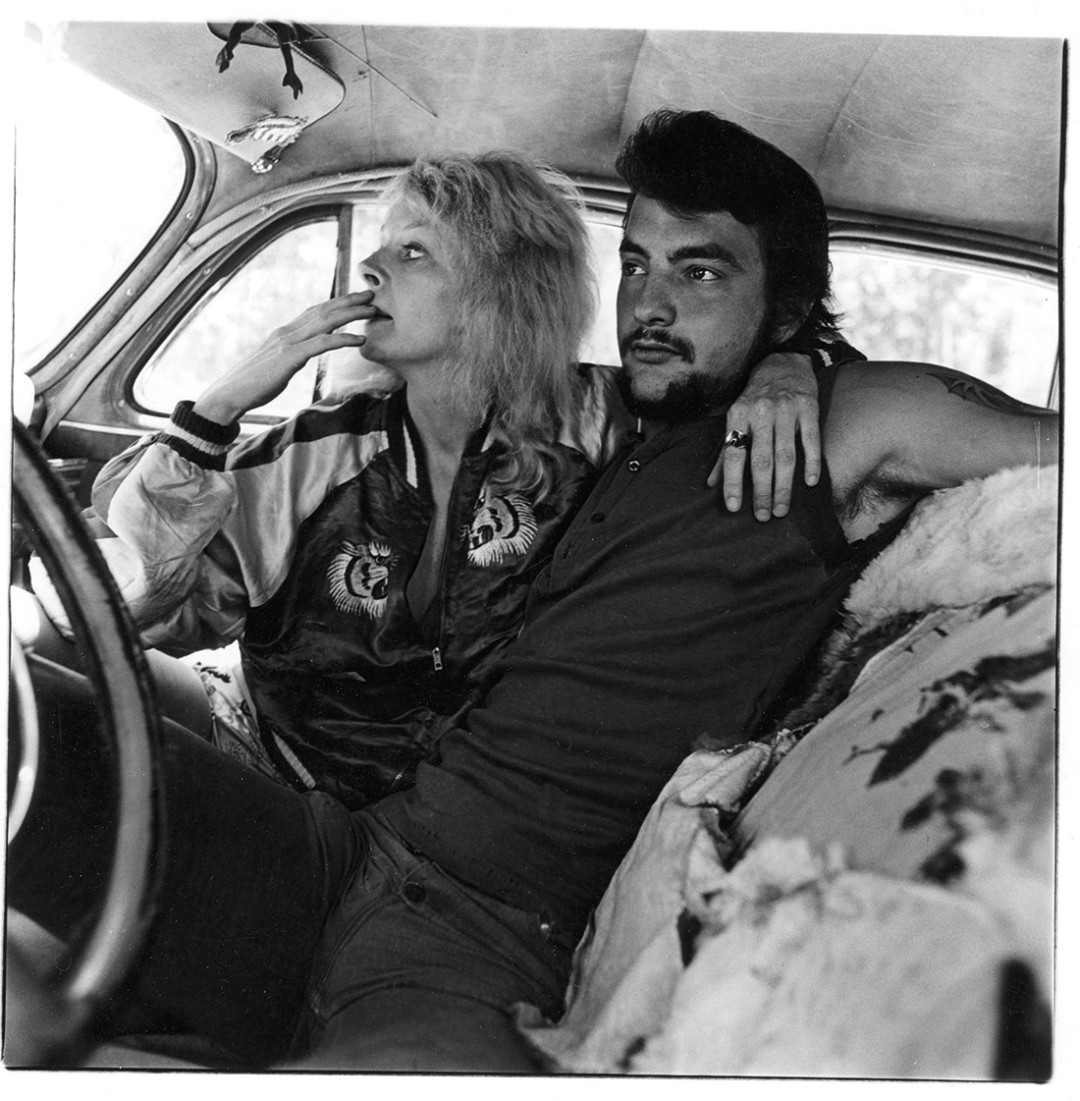

Image: Barbara Jo Revelle

The first wave of notable artists lured to Aspen were the photographers.

In the late summer of 1950, buoyed by the success of the Goethe Bicentennial but still on the hunt for ways to ensure the Aspen Institute’s future, Walter Paepcke called on two friends and colleagues to meet him by the pool at the Hotel Jerome. Egbert Jacobson was the Container Corporation of America’s design director; Ferenc Berko was a Hungarian-born photographer with roots in the Bauhaus—the influential German school of modern art and design that had run from 1919 until 1933—who had settled in Aspen in 1948 and had documented the events of the Goethe Bicentennial. Out of this exploratory meeting came two bold ideas: a conference on design (about which more later) and a conference on photography. Why not, Paepcke reasoned, bring the country’s leading photographers together for a conference in Aspen the very next year, just when the fall colors were beginning to show? Berko, who had a particular interest in color photography, agreed, and he and Jacobson began to make calls.

A steering committee boasting such notable figures as Beaumont Newhall, a historian of photography who in 1940 had been the founding curator of the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and Edward Steichen, who was both a pioneering modernist photographer and Newhall’s successor at MoMA, convened in New York the following July. After much discussion, the committee recommended postponing the conference for another year, but Paepcke was adamant that they move forward, if only as a prelude to a larger conference the following year.

Paepcke’s instincts proved right, and that September a veritable who’s who of American photography assembled in Aspen for the remarkable event that was the First Photographic Conference. Ansel Adams and Minor White, photographic poets of the natural world; perceptive, incisive realists Berenice Abbot and Dorothea Lange; and others like Eliot Porter, Laura Gilpin, Barbara Morgan, Frederick Sommer, Herbert Bayer, and, of course, Berko all attended. As Beaumont Newhall recounted soon afterward, “We talked photography from breakfast until after midnight. … Every meal in the Hotel Jerome was a symposium. No table was large enough to accommodate all who wanted to sit together. … Around the swimming pool, in the bar, on the street corner, little groups continued discussions. … As one of the conferees said, ‘I had to expand or explode.’”

At a moment when photography was still struggling for legitimacy as an art form, the conference provided a venue not to ask whether photography was an art, but, as Newhall put it, “to determine what kind of art it is” and to consider “the place of photography, and particularly the photographer, in the world today.” The conferees departed Aspen invigorated by the experience. Ansel Adams, whose iconic pictures of the Maroon Bells were taken during the conference, wrote to Paepcke with Nancy Newhall that “it was easily one of the most important events in contemporary photography.”

Despite the enthusiastic response, the First Photographic Conference was not followed by a second. But a generation later the Hotel Jerome once again became a locus of contemporary photography through a workshop and residency program called the Center of the Eye (COE). Founded in 1968 by photographer Cherie Hiser, who moved to Aspen in 1965 after studying with Ruth Bernhard, Imogen Cunningham, and Minor White, COE brought leading photographers of the day to Aspen to teach summer workshops and, oftentimes, to mount exhibitions of their work. The 1969 instructors included such heavyweights as Paul Caponigro, Bruce Davidson, Lee Friedlander, and Jerry Uelsmann. In the five years between 1968 and 1973, dozens of the world’s finest photographers—from Henri Cartier-Bresson and Minor White to Garry Winogrand, Larry Clark, and Robert Heinecken—led workshops under its auspices. In 1973, the Center of the Eye moved its base of operations from the Jerome to the newly incorporated Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Snowmass Village, effectively merging with an organization that had until recently been known as the Center of the Hand, reflecting its status as the ceramics equivalent of the COE.

An installation on Cooper Avenue from the 1966 International Design Conference in Aspen. The piece was a topographical map made of separated layers of plastic.

DESIGN

INTERNATIONAL DESIGN CONFERENCE IN ASPEN

The annual meeting of top designers probed social issues of the day as much as it did design.

In 1951, two years after the Goethe Bicentennial, Egbert Jacobson and Herbert Bayer, with the support of Walter Paepcke, organized the first of what would become the annual International Design Conference in Aspen, or IDCA. They conceived of the conference as an opportunity to bring artists and designers together with leaders of business and industry. As Jacobson wrote to Paepcke at the time, the conference was entirely in keeping with the ideals of the young Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies, since “questions of design are as vital to humanism as music, literature, and philosophy.”

That first June, some 250 attendees and their families assembled for four days of presentations on the theory and practice of design. The title of the inaugural conference, “Design as a Function of Management,” was chosen to lure the business community, of which Paepcke was perhaps the most zealous but hardly the only convert to the philosophy of good design. Appearing alongside such notable architects and designers as Louis Kahn, Charles Eames, Josef Albers, and George Nelson were Stanley Marcus, head of the department store Neiman-Marcus; Charles Zadok of Gimbel’s department store in Milwaukee; and William Connally of Johnson’s Wax, who pointed to the benefits his company enjoyed in publicity and corporate image as a result of its striking modern headquarters designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

The IDCA quickly established itself as a preeminent forum for designers and those interested in the problems of design. Over the course of the 1950s, its focus gradually shifted away from the practicalities of promoting good design within corporate culture and toward such larger cultural topics as “Ideas on the Future of Man and Design” (1956) and “Design and Human Problems” (1958), eventually broadening its scope to include almost any topic that the IDCA board deemed relevant to the field. And so, throughout the late 1950s and 1960s, the various design professionals in attendance were treated to presentations not only from their professional peers, but also by such diverse figures as mathematician Jacob Bronowski (1957 and 1967); sociologist C. Wright Mills (1958); ophthalmologist Peter Kronfeld (1961); virologist and polio vaccine discoverer Jonas Salk (1962); composer John Cage (1966); experimental filmmakers Len Lye (1959), John Whitney, and Stan VanDerBeek (both 1967); and even—somewhat improbably—actor Peter Ustinov (1969).

By 1970, the IDCA had evolved into an established institution representing the crème de la crème of the fields of graphic design, industrial design, and architecture. 1970 was also the year that the fissures and conflicts that had arrived in the late 1960s between an emerging counterculture and the social, political, and economic “establishment” made their presence felt at the IDCA. The theme of the 1970 conference was “Environment by Design.” If, for the conference’s organizers, design amounted to a problem-solving activity in the mutual service of industry and culture, for an emerging generation of more politicized designers it held an entirely different meaning. In their view, design was wrapped up in, and ultimately responsible to, a larger set of social, economic, and environmental factors, including the exploitation of natural resources and the problem of unchecked population growth.

A coalition of dissenting students, their young professors, environmental activists (including the Bay Area media art collective Ant Farm), and a radical French delegation led by the sociologist and philosopher Jean Baudrillard disrupted the conference proceedings. The protests culminated in the reading of and voting on a series of resolutions criticizing the intellectual limitations of the conference and, ultimately, the design profession itself.

Although the IDCA continued on for another two decades, the 1970 conference marked the end of an era. As the chair of its stormy final session, historian Reyner Banham, later summed it up: “the brashly elitist self-confidence” of the conference’s early years “dissolved before the social introspection and cultural awareness” of the late 1960s. “We got ourselves together again,” Banham remarked, “but an epoch had ended.”

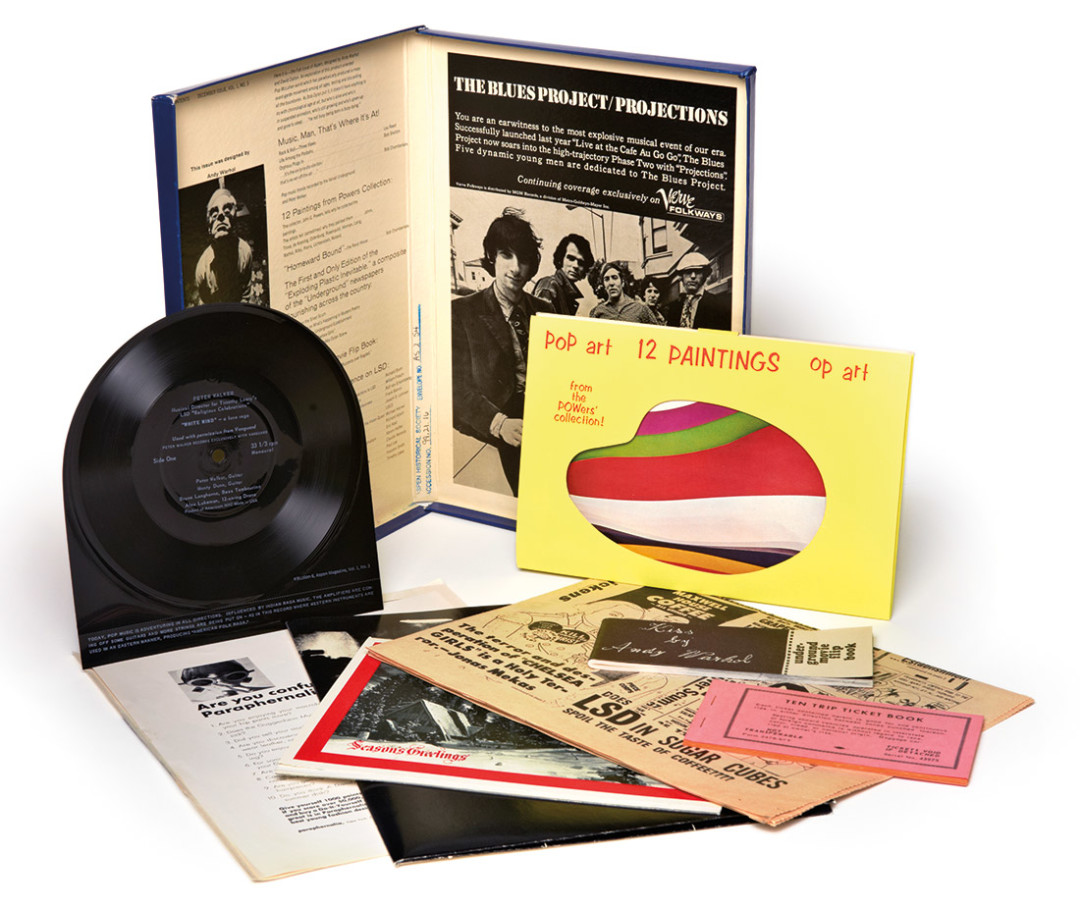

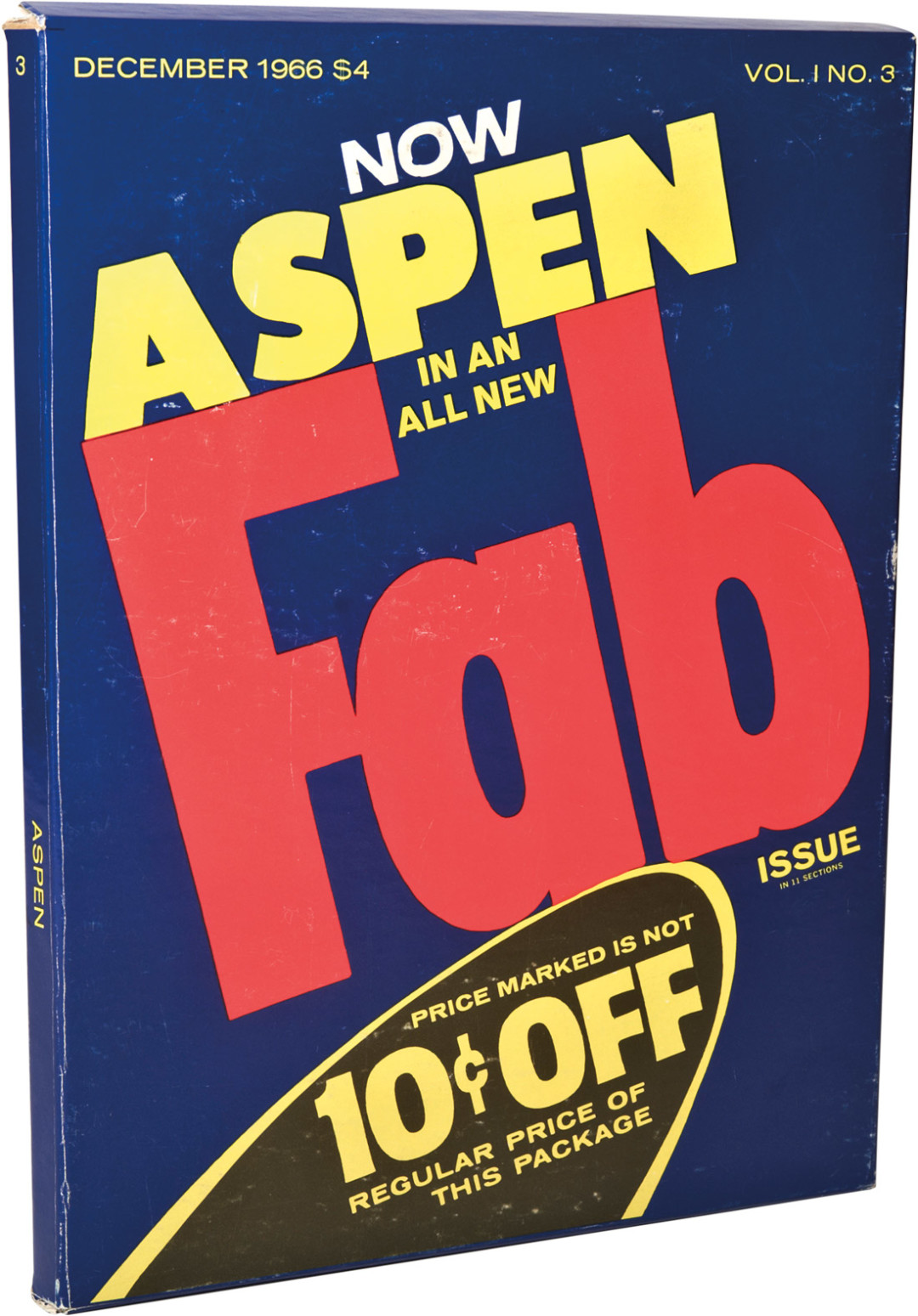

Aspen, the “magazine in a box,” Vol. 1, No. 3, designed by Andy Warhol and David Dalton.

MULTIMEDIA

ASPEN: THE MAGAZINE IN A BOX

A “magazine” from the 1960s reflected Aspen’s atmosphere of free thinking.

In other words, all the civilized pleasures of modern living, based on the Greek idea of the ‘whole man’ as exemplified by what goes on in Aspen, Colorado, one of the few places in America where you can lead a well-rounded, eclectic life of visual, physical, and mental splendor.” Such was editor and publisher Phyllis Johnson’s summation, in its inaugural issue, of Aspen, the self-described “magazine in a box.” Although it was initially slated to appear six times a year, ultimately only ten issues were published between 1965 and 1971.

Image: Tony Prikryl

But what issues they were. Aspen’s first two were dedicated to such topics as skiing, nature, jazz and modern classical music, and excerpts from the Aspen film and design conferences. But issue three—edited by Pop Art maestro Andy Warhol and rock critic (and soon-to-be Rolling Stone founding editor) David Dalton—quickly swapped genteel sophistication for downtown cool. Designed to look like a box of brand-name detergent, the issue’s “Fab” contents resembled a rock ’n’ roll press kit, complete with a flexi-disc containing the first release by the Velvet Underground; a reversible movie flipbook with snippets from Jack Smith’s Buzzards Over Bagdad on one side and Andy Warhol’s Kiss on the other; a one-off newspaper called The Exploding Plastic Inevitable produced by Warhol’s Factory studio; a series of writings on the effects of LSD in the form of a book of tickets; and more.

Subsequent issues focused on such topics as media theorist Marshall McLuhan, minimalism and conceptual art, performance, and the culture of psychedelia. In its relatively short lifetime, Aspen upended all traditional ideas of what a magazine could be, and its experimental format continues to resonate to this increasingly virtual day. As Johnson once proclaimed: “You don’t just read it: you hear it, hang it, feel it, fly it, sniff it, taste it, fold it, wear it, share it, even project it on your living room wall.”

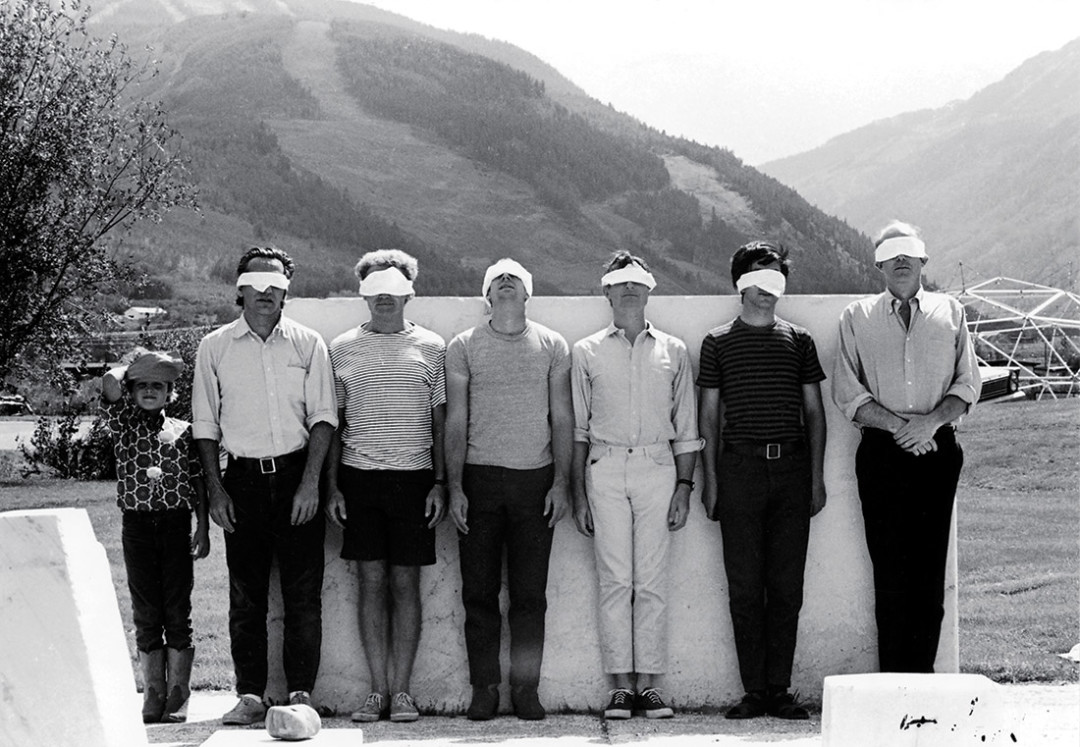

1967 Aspen artists-in-residence, from left: an unidentified child, Allan D’Arcangelo, DeWain Valentine, Robert Morris, Roy Lichtenstein, Les Levine, and Claes Oldenburg.

Image: Cherie Hiser

INSPIRATION

ASPEN INSTITUTE/ACCA ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE

For five years, many of the art world’s heavyweights spent their summers in Aspen.

The summer of 1966 probably finds more fine art in Aspen than in most U.S. cities,” wrote prominent collector, former president of Prentice Hall publishers, and Aspen Institute trustee John Powers in that year’s August 4 edition of the Aspen Times. The truth of such a statement was largely due to an ambitious artists-in-residence program that Powers himself had been instrumental in founding the previous summer. Established by the Aspen Institute, the program was the brainchild of Powers and his wife, Kimiko, along with two New York art-world power couples: fashion designer Larry Aldrich (who had recently founded the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Ridgefield, Conn.) and his wife, Wynn, and architect Armand Bartos and his wife, Celeste. Between 1965 and 1970, Aspen played host to many of the most important artists and critics of the era, representing such ultra-contemporary developments as color-field painting, pop art, minimalism and conceptual art, earthworks, process art, happenings, and light and space art.

Among the projects undertaken by the 1967 class of residents, now operating under the auspices of the newly founded Aspen Center of Contemporary Art, was an event called Culture-In, a weekend-long Happening that included installations and musical performances in the artists’ studios on the second floor of the Brand Building (which today houses the Baldwin Gallery, among other businesses); an afternoon softball game for which Claes Oldenburg created an enormous Soft Baseball Bat; a symposium entitled “A Definition of the Avant-Garde,” moderated by Powers; a “mock-panel” moderated by Art News critic (and future New Museum director) Marcia Tucker; screenings of avant-garde films by Stan Brakhage, Peter Kubelka, and Arnulf Rainer; and an Oldenburg performance entitled Chapel that involved the artist, wearing a series of outrageous costumes, reading from local newspapers.

As Powers described it, the purpose of the program was “to bring leading artists working in the contemporary field to Aspen with freedom to pursue any activities they wish. Their association with one another provides cross fertilization of ideas especially in the atmosphere of Aspen which is so much less turbulent than that of New York or any other city where artists usually live.” Whatever the reasons, their time in Aspen indeed led a number of artists in important new directions. Claes Oldenburg’s Giant Soft Drum Set was inspired by the surrounding landscape; Robert Morris made his first experiments with industrial felt in his studio in the Brand Building; Carl Andre took the opportunity to expand his experiments with modular sculpture into the outdoors; and Dennis Oppenheim conducted a series of videotaped performances now collectively known as his Aspen Projects. Although the program lasted for only six years, for a few months each summer from 1965 through 1970 Aspen became one of the nation’s most vital centers of artistic activity.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Valley Curtain, Rifle, Colorado, 1970–72, Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 1972 Christo

INSTALLATION

Valley Curtain It lasted barely one day, but Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Colorado project is legend.

Image: Courtesy: Janet Geib Pretti

Today, the artistic duo of Christo and Jeanne-Claude are perhaps best known—in this country at least—for The Gates, their 2005 installation of 7,500 gates, adorned with free-hanging saffron-colored panels, winding through New York City’s Central Park. By the time they arrived in Aspen for what would be the final summer of the Aspen Center of Contemporary Art’s artists-in-residence program in 1970, the pair had already achieved international recognition for wrapping various buildings, monuments, and even a 1.5-mile-long section of the Australian coastline, in enormous quantities of fabric and rope. (Wrapped Coast included one million square feet of fabric and thirty miles of rope.)

Earlier in the year, they had conceived of a project called Valley Curtain, Project for Colorado, which would suspend an enormous curtain of woven synthetic fabric from a 1,500-foot-long steel cable anchored on opposite sides of a valley. Although neither artist had been to Colorado, they had heard about it from the Powers and the Bartoses, and they decided use their ACCA residency to scout for viable locations. Driving up and down the valleys of the Western Slope in a borrowed vehicle, Christo and Jeanne-Claude came up with eleven possibilities, including sites in the Maroon Creek and Castle Creek valleys, just outside of Aspen. But their first choice was a bit farther afield: the Rifle Gap, outside the small town of Rifle, some sixty miles northwest of Aspen.

Image: Courtesy: Janet Geib Pretti

After securing the necessary permits and working through the engineering, construction on Valley Curtain began the following summer. The project eventually took twenty-eight months to complete, but on the morning of August 10, 1972, a group of thirty-five construction workers and sixty-four temporary helpers, art-school and college students, and “itinerant art workers” tied down the last of twenty-seven ropes that secured the 200,200-square-foot orange nylon fabric curtain to its moorings. At a maximum height of 365 feet from the valley floor, the curtain stretched 1,250 feet across the valley from one mountainside to the other. The curtain’s bottom ultimately remained just clear of the ground, while a ten-foot-high skirt attached to the lower part of the curtain visually completed the scalloped areas between anchor points.

On August 11, a mere twenty-eight hours after its completion, gale-force winds made it necessary to begin removing the work. Valley Curtain lives on, however, in the form of drawings and collages, a book, and an Academy Award–nominated film by Albert and David Maysles. The project’s success at turning “skeptical iron-workers into astonished fans” has made it a touchstone in Christo’s current efforts to realize Over the River, a project to temporarily suspend nearly six miles of silvery, luminous fabric panels high above the Arkansas River at eight points along a forty-two-mile stretch of the river between Salida and Cañon City in south-central Colorado.

VISIONARY

ASPEN MOVIE MAP

Navigating through town via an interactive computer screen is not cutting-edge today. It was in 1979.

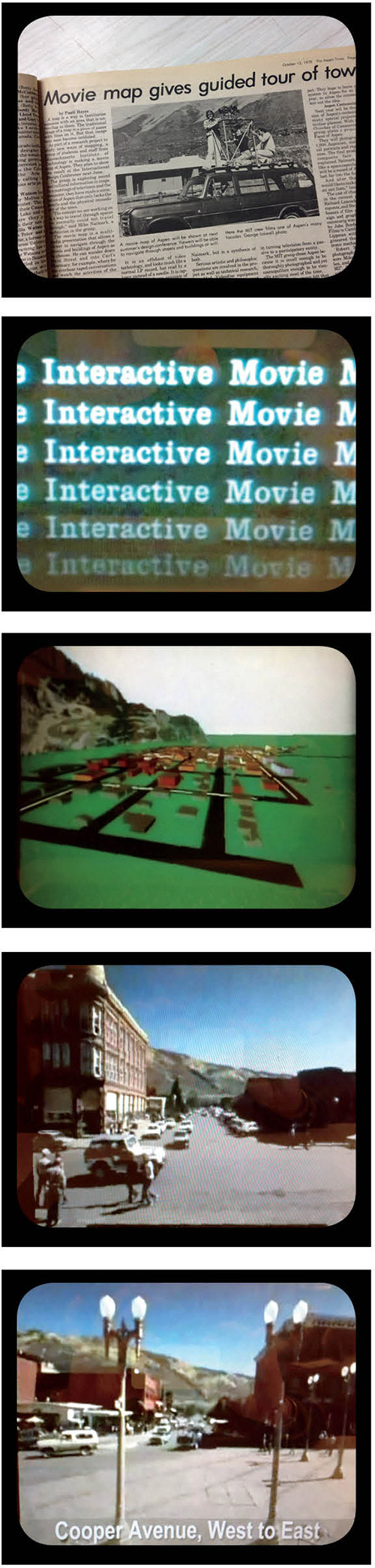

Since Google Street View went live in May of 2007, it hasn’t been a particularly shocking experience to see camera-mounted Google vehicles slowly driving up and down the streets of countless cities across the U.S. and around the world. Not so many years earlier, such a sight would have been unusual to say the least, and the whole enterprise would have sounded like science fiction to many. But thirty years before Street View, in 1978, a small squadron of students and faculty from MIT’s Architecture Machine Group and Center for Advanced Visual Studies descended on Aspen to do essentially just that. The result: a revolutionary interactive virtual travel system they dubbed the Aspen Movie Map.

First demonstrated in the summer of 1979, the Movie Map let users choose their own routes through the streets, listen to interviews with Aspen locals, toggle back and forth between early fall and winter views, even go back in time to see historic photos of existing buildings. To create the movie map, four 16mm stop-frame motion picture cameras were mounted to a gyroscopic stabilizer on top of a camera car. A fifth wheel trailing behind the car triggered the cameras every 10 feet. Every day between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m., the car was carefully driven down the center of every street and around every corner in Aspen, the four cameras capturing simultaneous front, back, and side views as the car made its way through the city.

Newspapers picked up the curious story (top);

screen captures of the interactive Aspen Movie Map.

The resulting footage was assembled into a collection of discontinuous scenes and then transferred to laserdisc, the newly developed analog precursor to today’s DVD and Blu-Ray technologies. Each optical videodisc could store up to thirty minutes of video, or 54,000 images, and to the footage shot from the vehicle-mounted cameras the team added photographs of every façade in Aspen, historical images, and additional data that allowed users to explore certain buildings in greater depth.

Accessed via a touch-screen interface, the Movie Map was a pioneering example of interactive computing and hypermedia systems. The project’s success also says something about the character of Aspen itself. As various participants have since remarked, the process of collecting footage was hardly inconspicuous, but Aspenites were “characteristically nonchalant” or “sufficiently odd” to a degree that they didn’t mind the unlikely presence of a homemade film truck driving up and down the middle of the streets for weeks on end at various points during the year.

But that was Aspen: a place where, by that point, the unusual had become the expected.