Pop Art Preserve

Thirty miles from Aspen, just past mile marker 13 heading downvalley on Highway 82, the second road on the right beyond the gravel pit leads to a minimalist, rusted metal gate that recalls a peeled-pole ranch fence. The road winds through sage, piñon, and juniper, over cattle guards. Antique farm implements rust in the tall grass. Mount Sopris, snow-streaked, floats on the southern horizon.

From a distance, the Powers Art Center, a 100-by-100-foot minimalist cube of Colorado red sandstone, seems surprisingly modest. Smooth blocks interrupted only by horizontal rows of rough-cut stone could pass for a well-designed rural utilities building. The sandstone, from Lyons, Colorado, is the same color as the rock outcroppings on the surrounding hills. Except for the minimalist pergola that partly shades a granite terrace with a reflecting pool, the building is free of ornament. By no means small, it is dwarfed by the expanse of land around it. It feels sheltered—from the wind, from the outside world—by the hills rising behind and the distance in front. The 12,953-foot Sopris looms. Birds cheep. The whine of a truck passing is barely audible.

The Powers Art Center designed by Hiroshi Nanamori, sits on a ranch above Carbondale. Outside, the landscape and sky dominate. Inside, it's all about Jasper Johns.

Image: Derek Skalko

Experiencing the site feels somehow like a privilege, as if you’ve gained access to another person’s private sanctuary. And, in a way, you have. The Powers Art Center, according to Melissa English, its director, was built by Kimiko Powers as a tribute to her husband, John Powers, to share with the public the couple’s extensive collection of Jasper Johns works on paper and the natural environment they both loved.

John Powers first came to Aspen in the early 1960s, at the invitation of Alvin Eurich, president of what was then the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. Powers had studied at Princeton, earned a law degree from Harvard, worked briefly as an attorney, and then longer at the publishing house Prentice Hall, where he was president when he retired in his late forties. Collecting art became his passion—contemporary American art and fifth- to nineteenth-century Japanese art. He collected for himself, for love of the work, he often said, rather than for investment, and without a curator.

Image: Derek Skalko

Harry Abrams, the art publisher, and Leo Castelli, the New York power gallery owner who gave Jasper Johns his first one-person show, sometimes advised him. John and Kimiko Powers, collected Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Johns. The couple accumulated 290 Johns prints, almost every limited-edition print the artist has so far made, and built one of the largest and most highly respected private contemporary art collections in the world.

The Powers loved the Roaring Fork Valley. They bought a house in Aspen and eventually the 460-acre Carbondale ranch that the new museum now sits on, spending five or six months a year there. John served on the Institute’s board, and often as a moderator. In partnership with the Institute, he and Kimiko, with Celeste and Armand Bartos and Larry and Wynn Aldrich, two other art-world power couples, founded the Aspen Institute for Contemporary Art and invited pop art stars of the 1960s—Warhol, Oldenburg, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, Carl Andre, James Rosenquist, Robert Indiana, De Wain Valentine, and Christo—to an artist-in-residence program during the summers from 1965 to 1970. The artists were given studio space on the second floor of what is now the Brand Building, then owned by Robert O. Anderson, who was the CEO of ARCO and chairman of the Institute’s board. Powers wrote a weekly art column for the Aspen Times. He played jazz once a week with Walt Smith at the Sopris Restaurant.

Image: Derek Skalko

When John Powers died in 1999, Kimiko decided that a fitting memorial to his life as a collector and patron of the arts and part-time resident of the Roaring Fork Valley would be a private museum on the Carbondale ranch. He’d loved the land, she has said, and wanted to be buried within sight of Sopris. She formed the nonprofit Ryobi Foundation to steer money toward the project, and chose Japanese architect Hiroshi Nanamori to design the building, with assistance from Glenn Rappaport of Basalt-based Black Shack Architects, to show their collection of Jasper Johns works on paper.

What Nanamori did, Rappaport says, is a reinvention of modern architecture in a rural and remote setting. “It’s contemporary. It blends with the landscape. It’s green. It’s part of what I call post-agricultural expressionism—taking agricultural typologies and overlaying them onto a building with a completely different program. It’s a world-class museum, not a place where they have cows.”

The museum’s entrance is defined by absence. A piece of the building’s basic cube shape, the lower southwest corner, was left as a space. The upper floor is cantilevered over that space and the edge of the pergola. Under it, glass reveals the building’s two-story central atrium, an Andy Warhol portrait of John Powers with saxophone, and a plaque that informs visitors of the museum’s origin and purpose.

Red, yellow and blue - the words and the colors - appear repeatedly in Jasper Johns's work.

Image: Derek Skalko

The interior space is deeply peaceful, focused on the art. The floor is black Cambrian granite; the walls are shades of white. The stairs to the upper galleries are stone, with a transparent half-wall anchored by a stainless-steel rail. The rail is solid—the feel of it in the hand was important to Nanamori—but also in its lightness visually unobtrusive. The galleries flow off of the atrium, from which the landscape mediated by the pergola is visible. The effect is quietly stunning.

The opening show of 120 prints begins in the gallery behind the Warhol portrait. The prints are hung roughly chronologically. Coathanger I 1960, the first image on the wall, is a lithograph made with one stone, a black and white image of a wire hanger on a nail, on a heavily scratched ground.

An iconic figure of the pop art world, Johns, who is still making paintings, prints and sculptures at 84, works with repeating images of seemingly prosaic objects—the American flag, wire coat hangers, rulers, targets, maps, Savarin coffee cans, light bulbs, words, handprints. The prints usually come after the paintings, often not until years later. The images are representational, but the objects often float in space or hang on wires, or are nailed to surfaces defined by color fields or black fields or scribbles. The prints are explorations of color and the absence of color, line and shape, concept and form.

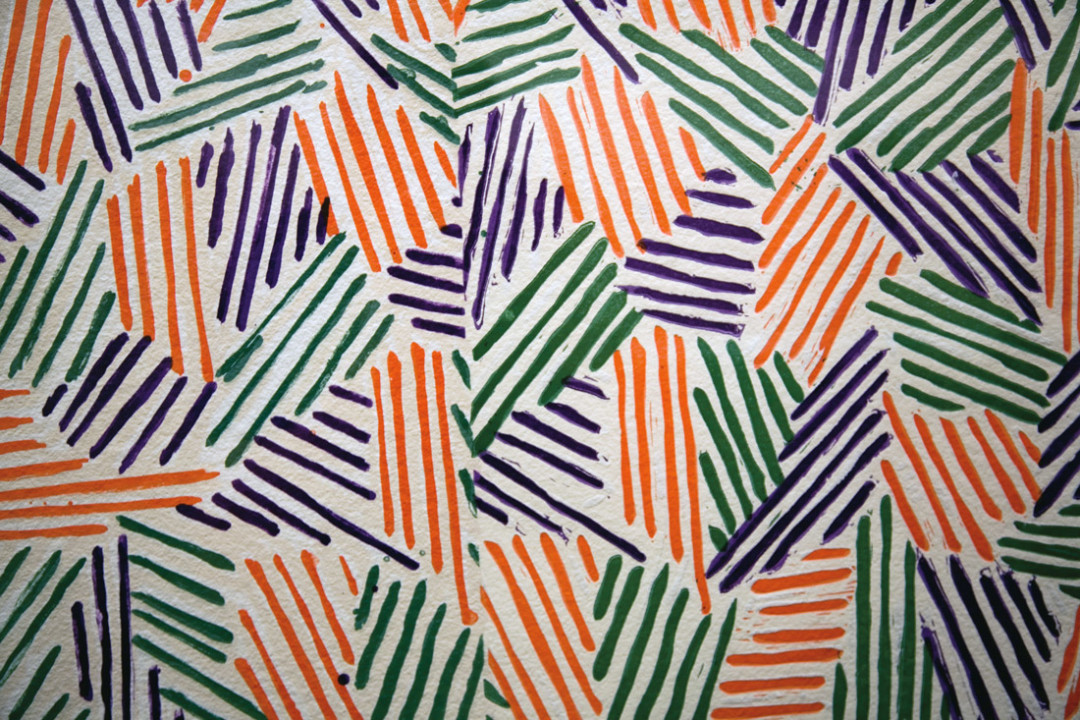

Detail of Scent, a lithograph, linoleum cut, and wood cut.

Image: Derek Skalko

Moving from gallery to gallery here, it is possible to see Johns’s range—lithographs made with one stone, with two stones, or with nine stones, with stones plus aluminum or copper plates, or with rubber stamps. Sometimes the actual object is embossed or attached. He uses intaglio on copper plates and aluminum plates. He has used sheets of lead. A poster for a 1978 show at the Whitney, an image of brushes in a Savarin coffee can, is a lithograph made with twenty-two aluminum plates. There are prints with flags, rulers, forks, spoons, numbers, words, a Frank O’Hara poem, as well as prints that are entirely patterns of lines and fields of color.

Johns’s juxtaposing of word and idea, idea and object, is intellectual and sensual, playful and intense. The beauty and cerebral-ness of his work appealed to Powers. Johns became hugely successfully critically and commercially, but the Powers not only collected Johns’s work, they lived with it. They became, Kimiko Powers has said, lifelong friends.

Time with the art is one of the things Kimiko Powers wanted to share, English says. The first show will hang for a year.

Image: Derek Skalko

Inside and outside the spaces are designed to offer time for reflection and study.

In the library, the Takashi Nakazato ceramic vessels, the carefully curated books, the two tables and twelve chairs, even the library lamps, seem designed to facilitate and inspire study. The shelves are wood, thick, solid. The books include tomes by and on Andre, Christo, Willem de Kooning, Lichtenstein, Johns, Oldenburg, Robert Smithson, Mark Rothko, Warhol, Garry Winogrand—the stars of the contemporary art world. On the wall are six of Johns’s lead reliefs, including a flag, a slice of bread, a light bulb, and a panel from The Critic Smiles series, this one a toothbrush with four molars where the bristles would be, the words on the box beneath the brush. High School Days is an embossed Oxford shoe with a small round mirror on the toe. It would be easy to spend days in the library alone.

Outside the grass is blowing, the water rippling. The breeze is steady. Solar arrays on the roof bank the sunlight. A shallow geothermal field system keeps the interior temperatures steady. The net energy use is close to zero. The site and the building are deeply complementary. Colorado’s brilliant sunlight and the spectacular views are mediated by the columns and connecting beams of the pergola. The columns and beams define an absence, the building’s form without solidity, a negative space that mirrors the building’s actual space. They draw the eye from the outside in and from the inside out.

Like the man, the Powers Art Center is elegant, understated, thoughtful, influenced by East and West. Its physical form embodies a Japanese aesthetic of spare simplicity and a rural western understanding of its place in the landscape.

The minimalist, rusted metal gate is open Monday through Thursday from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Admission is free.

“We’re going to be here forever,”

English says.

Image: Derek Skalko