Artist Enclave Anderson Ranch Celebrates Its 50th Anniversary

Construction of new buildings in the 1990s increased the Ranch’s campus to 55,000 square feet.

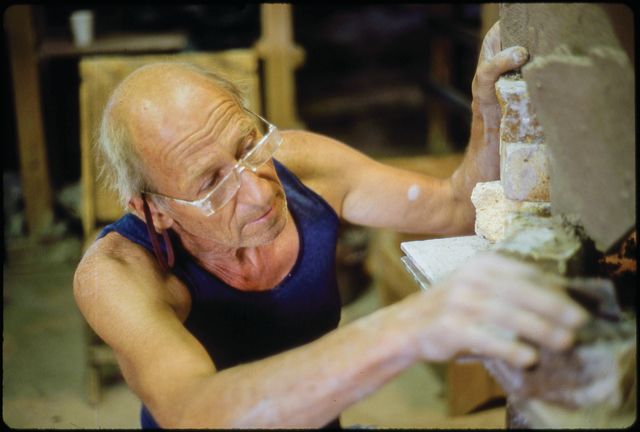

When I first met Paul Soldner—the visionary and charismatic founder of Snowmass Village’s Anderson Ranch Arts Center—at a reception in 2000, his reputation as a brilliant ceramic artist preceded him. He was renowned for building impossibly monumental clay sculptures eight and nine feet tall that erased the line between craft and art, as well as for popularizing the ancient Japanese firing technique of raku, which imparts unpredictable patterns to the surface of a pot. (Raku was also a metaphor for Soldner’s philosophy of art: he valued exploration and risk-taking, principles that informed his vision for Anderson Ranch). From my time in the 1980s as an associate of New York’s American Craft Museum (now the Museum of Arts and Design), I knew Soldner was a star, right up there with his teacher and mentor Peter Voulkos, renowned Japanese potter Takashi Nakazato, and sculptor Ron Nagle—all of whom would teach or lecture at Anderson Ranch over the years.

Paul Soldner at work in the ceramics studio, 1988.

I had, however, missed the memo on Soldner the individual. I was totally unprepared to meet a man wearing a sarong and sporting neon-green toenail polish, an iconoclast who, I subsequently learned, liked to work scantily clothed and was famous for hot-tub parties at the Aspen home he and his wife, Ginny, built in the summers over the 10-year period from 1956 to 1966. As multifarious in his work and lifestyle as Soldner, who died in 2011, was, his vision for Anderson Ranch was simple: “It’s a center, not a school. We’re different.” Community is paramount. Teachers need to be practicing artists, and students learn by doing and observing.

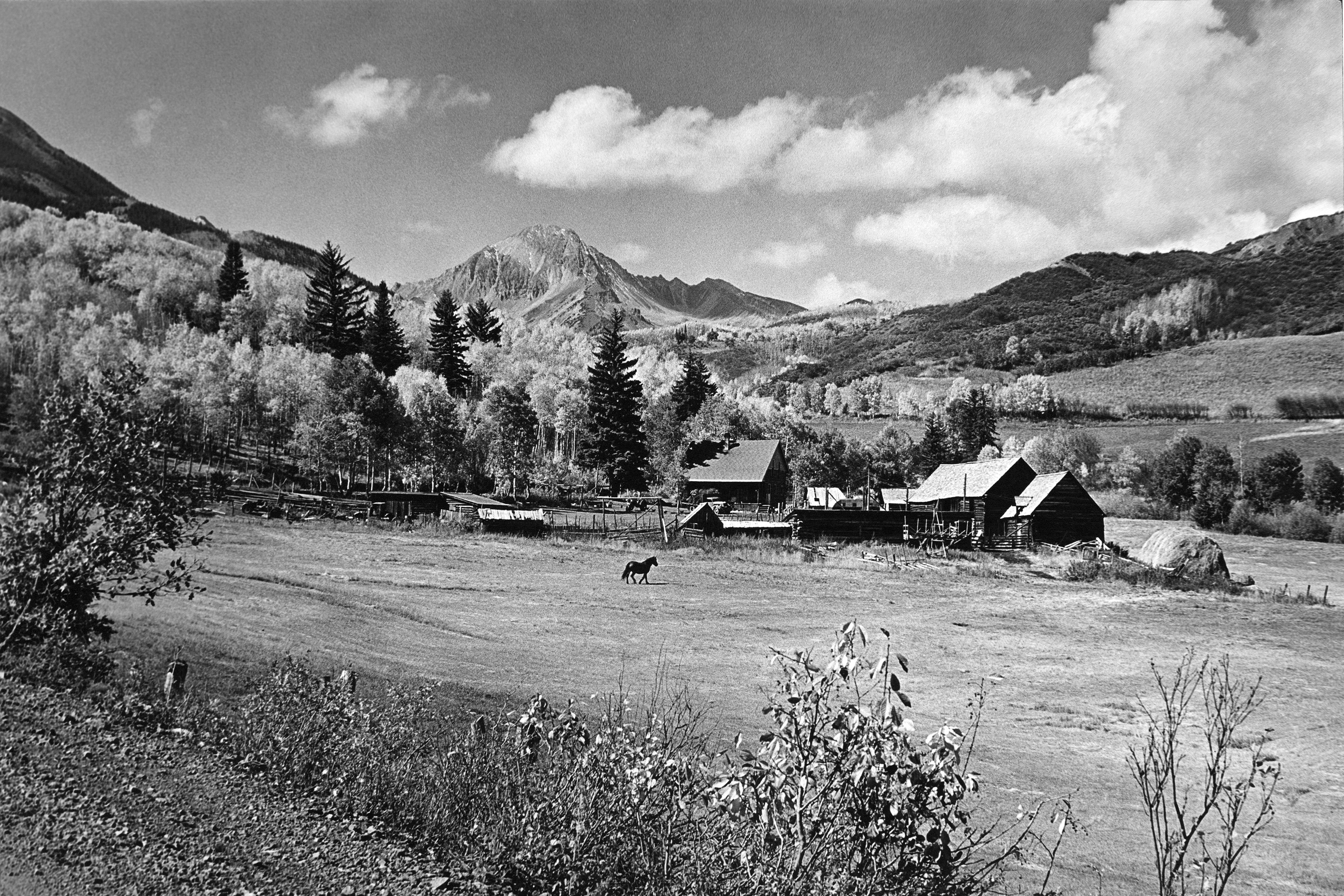

Part of the doing involved finding studio space for the burgeoning number of Aspen locals eager to learn ceramics. By serendipity, the Janss Corporation—developers of the fledgling Snowmass resort and ski area in 1966—envisioned an art center as part of the base village amenities and asked Soldner to select a suitable location from one of the available working ranches in the Snowmass area. He chose the old Anderson Ranch sheep farm, and his first flock of students soon found themselves cleaning out manure from a sheep shed before they could lay the foundation for the center’s initial ceramics studio. Shortly thereafter, Cherie Hiser moved her Center for the Eye photography workshops from Aspen out to the Ranch, inspiring Soldner to name his program Center for the Hand. Seven years later, the two joined forces and renamed the larger enterprise Anderson Ranch Arts Center.

This summer, Anderson Ranch celebrates 50 years of a rich history that has made it a destination for beginning and seasoned artists from around the globe. Over the decades, the Ranch has expanded its offerings from ceramics and photography to include painting and drawing, furniture design, woodturning and woodworking, digital fabrication, sculpture, new media, printmaking, critical dialogue, and a children’s program.

In 1981, the Ranch launched its visiting artist program, bringing together a who’s-who of American artists—Ed Ruscha, Laurie Anderson, James Rosenquist, and Red Grooms, among others—to work with master printers Bud Shark and Craig O’Brien. Today the program brings in artists from all disciplines to work on specific projects, interact with workshop students, and share their work through public lectures. The artist-in-residence program also started in the 1980s, providing emerging and established artists 10 weeks of uninterrupted studio time to work on special projects. Currently there are 28 residencies each year, 14 in the fall and 14 in the spring. Since 1986, according to Doug Casebeer, the Ranch’s associate director and artistic director of ceramics, the Ranch has hosted nearly 589 resident artists from 43 states, 19 countries, and six continents. Ranch alumni comprise more than 30,000 students, 4,000 faculty, and several hundred visiting artists projects. Ranch artists have been included in the Whitney Biennial, received Fulbright and National Endowment for the Arts awards, and become MacArthur Fellows.

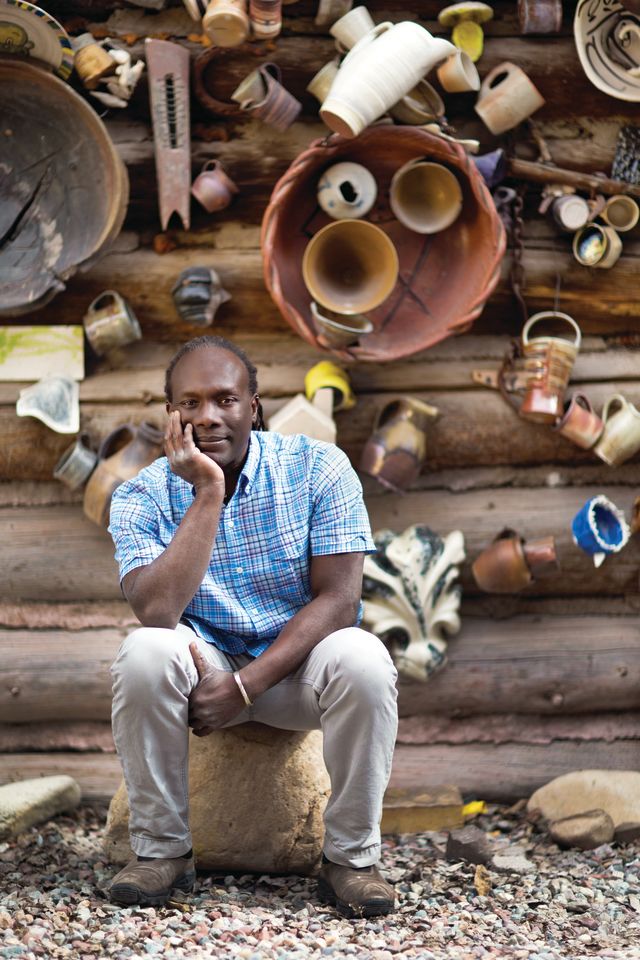

Ceramic artist and gallery owner Sam Harvey has a long history with the Ranch.

As the Ranch has continued to evolve, adding an annual art auction and destination workshops—Jamaica and San Miguel de Allende in 2016—to its plethora of programs, its mission has remained singularly focused: Anderson Ranch Arts Center enriches lives with art, inspiration, and community. Community is the key, as Soldner so clearly understood in 1966.

Here, three artists reflect on the past, present, and future of Anderson Ranch and how their experiences on its campus have influenced their own art.

Sam Harvey was an undergraduate in ceramics at Kansas City Art Institute when he first visited Anderson Ranch in the early 1980s. On the recommendation of one of his professors, Ken Ferguson, he arrived to take a workshop with Robert Turner, who, along with Ferguson, was considered a giant in the field of ceramics.

“The Ranch was much smaller and less structured in those days,” Harvey recounts. “There was no housing, and we brought our own sleeping bags and pretty much slept wherever we could. I remember one fellow slept in a treehouse. There were lots of potluck dinners.”

The Ranch was also very isolated, surrounded by cow pastures. “No one had a car, there were no free buses, and there was no place to go at night,” Harvey notes. “If you wanted to go to Aspen, you had to hitchhike.”

Despite the spartan accommodations, Harvey found his calling in ceramics that summer. “I went to an arts high school in New Orleans and had always planned to be a photographer or painter,” he says. Instead, after earning his BFA in 1984 he returned to the Ranch, beginning a 30-year relationship in which he has played many roles: summer intern, studio manager in ceramics, artist-in-residence, faculty member, and volunteer. For six years Harvey also assisted Peter Voulkos during his tenure as a visiting faculty member.

Eventually returning to graduate school, Harvey received his MFA in ceramics from Alfred University in 2001. Today he is a nationally known ceramic artist, a partner in the successful Harvey/Meadows Gallery in downtown Aspen, and a Ranch board member.

During his tenure at the Ranch, Harvey has seen many changes in the physical campus and programming. “The addition of the Wyly Painting Building in 1991 was an important marker in the Ranch’s development,” he says. In addition to the watercolor and landscape workshops already being offered, the new studio space allowed for classes in mixed media, oil, studies in color, and encaustic (a wax-based painting process), among many other subjects. “The Ranch began to attract more students in painting and grow enrollment,” adds Harvey. “The conversation around art became more conceptual and elevated.” The artist-in-residence program also expanded to include two visiting critics each term to give critical studio feedback to program participants, further expanding the discourse on art.

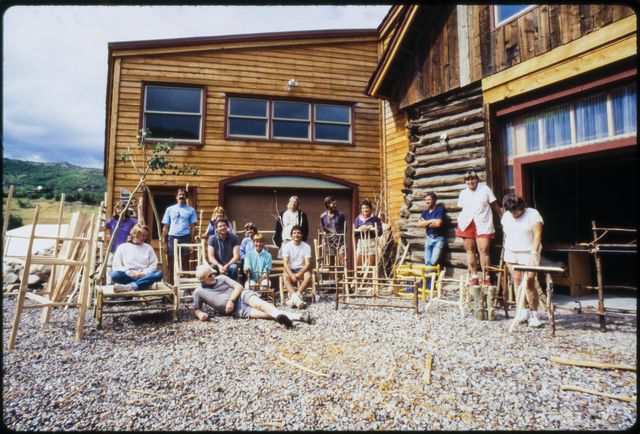

Students in a furniture design and woodworking workshop outside the Maloof Barn in 1988.

Continual evolution is a hallmark of Harvey’s own art, too. “My work is always changing,” he says. “I am constantly having a conversation with process. I make art to answer questions about the physicality of objects and the space they occupy, and to understand how things are built and organized.”

Another milestone for the Ranch was the construction of Schermer Meeting Hall in 1993, which provided a public venue for lectures by visiting critics, resident artists, and faculty, attracting audiences from throughout the Roaring Fork Valley. “Before Schermer, we used to put up tents for lectures,” Harvey reminisces. “There was a tent for the kids and a tent for sculpture. At the end of the summer we took down the tents, and that marked the end of the workshops.”

Most important for Harvey are the interdisciplinary opportunities the Ranch offers, which enable a cross-pollination of ideas that he calls unparalleled. “When Laurie Anderson came to work with Bud Shark in the printing program in the 1980s, it was a seminal moment,” says Harvey. “We all learned something.”

Trent Davis Bailey, currently an artist-in-residence in photography, also values the natural exchange of ideas and insights that the Ranch facilitates. “It’s empowering to be among a community of artists making remarkably different work in our studios,” he says. “We all share ideas, successes, and failures. We all learn from each other.”

Photographer Trent Davis Bailey is an artist-in-residence this spring.

Bailey is no stranger to the Ranch. In 2009, while studying photography and art history at the University of Colorado, he received a scholarship to take a weeklong workshop taught by Alex Webb, a renowned street photographer, and Rebecca Norris Webb, a photographer and poet. The workshop proved formative. “It inspired me to think more broadly about geography through photography—not just in a topographic, social, or economic sense, but also in an inward sense,” Bailey says. “I became more aware of how I was personally using photography to translate the physical world.”

In 2010, he returned to the Ranch for a four-month internship in photography and new media—assisting with weekly workshops taught by photographers, master printers, and digital artists—then moved to New York City. Among other jobs, he reconnected with the Webbs and worked as their assistant for three years.

While in New York, he found himself longing for the Colorado mountains and ruminating over his childhood memories there—impulses that acted as a catalyst for his project The North Fork. An excerpt from his project statement reads: “The North Fork is a place in my imagination. It is also a valley in my home state of Colorado. I have since used photography to piece together a map of my experience of this valley’s landscape and inhabitants—as well as my own emotionally complicated terrain of memory and family.”

During his residency, Bailey is taking advantage of the photography lab, which includes large-format ink-jet printers, computers with Adobe Creative Suite, a darkroom, color-controlled studio lighting, and a high-resolution film scanner. The combination of traditional and state-of-the-art equipment mirrors his embrace of both film and digital photography. “My generation came of age during the advent of the Internet and personal computers,” he reflects. “At 13, I used to skip lunch at school to work in the darkroom. After school, I’d spend hours on my dad’s computer hooked up to dial-up Internet. I enjoyed experimenting with these two very different technologies.” He adds, “I arrived here with a box full of color negatives, and I’m using the facilities to process all of my recent work.”

Anderson Ranch faculty member and designer Vivian Beer.

At 30, Bailey is represented by the Robert Koch gallery in San Francisco and is the recipient of the 2015 Snider Prize from the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago. Despite his growing success, he says, “I don’t care much for titles, but I hope—even later in life—I will still approach my work with the eagerness of an emerging artist. I want to maintain that buoyancy, to take risks, to grow and expand.” His current tenure at the Ranch is helping him to stay on that path.

Iconoclastic, innovative, out-of-the-box, revolutionary … all of these terms describe New Hampshire–based designer and furniture maker Vivian Beer, an Anderson Ranch faculty member since 2009 and the 2016 winner of Ellen’s Design Challenge on HGTV. Beer—whose preferred materials are metal, concrete, and auto-body paint—studied sculpture at the Maine College of Art and earned an MFA in metalsmithing from the Cranbrook Academy of Art. Between her degrees, she worked for two years as an architectural blacksmith, making decorative items in many historical styles. “I really had a classical arts background but fit well into Cranbrook’s metals program, which was guided intellectually by the history of the decorative arts,” she says.

The digital design and fabrication workshop that Beer will teach at the Ranch this fall integrates cutting-edge and traditional fabrication techniques. At her disposal will be the latest tools in the Ranch’s new FabLab: a CNC (computer numerically controlled) router, a CNC plasma cutter, a Makerbot Replicator 3-D printer, an Epilog laser engraver and cutter, a 3-D scanner, and a vinyl cutter. Welcome to Anderson Ranch’s future.

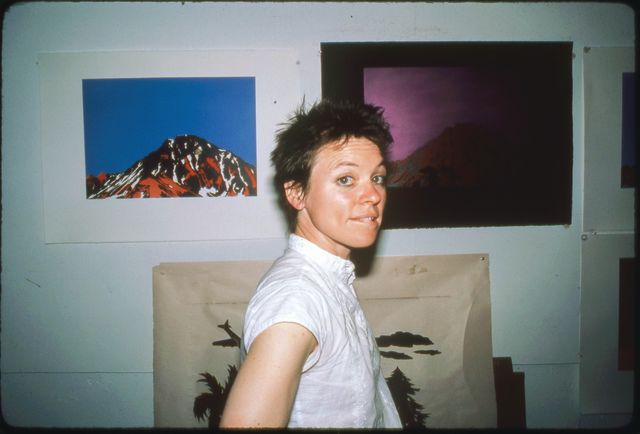

Laurie Anderson came to the Ranch in 1982 as a visiting artist.

“In the digital design program, we can start with a drawing on the computer, or we can throw it into the computer’s digital space with a 3-D scan of a handmade model,” Beer explains. When a design is complete, it’s transferred to the CNC machine to cut a full-scale model in plywood or metal. “With the model,” adds Beer, “we can go back and forth seamlessly between the actual world and the digital world in the computer program, making adjustments in design and scale.”

She acknowledges the Ranch’s foresight in creating a digital design program. “For the past 10 years, there has been a lot of trepidation in the craft and art world about computer design and fabrication—that nothing will be done by hand anymore—but it’s not true,” she says. “Hand-forming is still the most important technique a sculptor has. The FabLab at Anderson Ranch has incredible engineering tools that allow students to execute even more complex designs, but they will never replace the extraordinary power of hand work. They are just other tools for expression.”

Given her background in industrial design, the decorative arts, and sculpture, Beer says Anderson Ranch is a perfect fit. “I can teach in the sculpture department and build a whole course around a piece of equipment,” she says. “The Ranch allows me to be extremely creative.”

“Can I come?” It’s a question that Nancy Wilhelms, the executive director of Anderson Ranch, hears almost daily from top-tier artists around the country. “I think artists are astonished when they see the facilities and the equipment we have,” she says. “The word quickly gets out, and artists want to come to the Ranch to teach and work.”

Wilhelms has been at the helm since June 2013 and, with strong board support, grew the endowment by $2 million and increased the annual budget by more than $800,000—all part of maintaining the quality and diversity of the Ranch’s offerings. But what really excites her is interacting with students and faculty. A photographer herself, she has a fine arts degree from the University of Colorado and did postgraduate work at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). “I love artists. I love making art, talking about art, and spending quality time with workshop students and visiting artists,” she enthuses. “My job is really about building relationships.”

Of the Ranch’s more recent programs, Wilhelms is particularly proud of a scholarship partnership in which Anderson Ranch underwrites tuition, and colleges and universities underwrite room and board, for students attending summer workshops. “We ask the colleges to send their best seniors and graduate students who could not afford to come on their own,” she says. “It means our workshops are filled with eager, bright students with different points of view.” To date, the Ranch has worked with more than 65 colleges and universities, including Yale, CalArts, and RISD, bringing in more than 100 students each summer.

And then, of course, there are the 150-plus summer workshops for artists of all levels—including a new advanced mentored study program for documentary photographers and photojournalists—the visiting critics program, the featured artists series, and the much-loved annual art auction and community picnic, as well as a week of events to mark the golden anniversary.

Vivian Beer likely speaks for many when she says, “The next 50 years for the arts will be phenomenal. Anderson Ranch fosters a passion for art and encourages the exchange of ideas. I can’t wait to see what happens next.”