Acclaimed Novelist Alice McDermott to Launch Aspen’s Winter Words Series

Image: Courtesy: Aspen Words

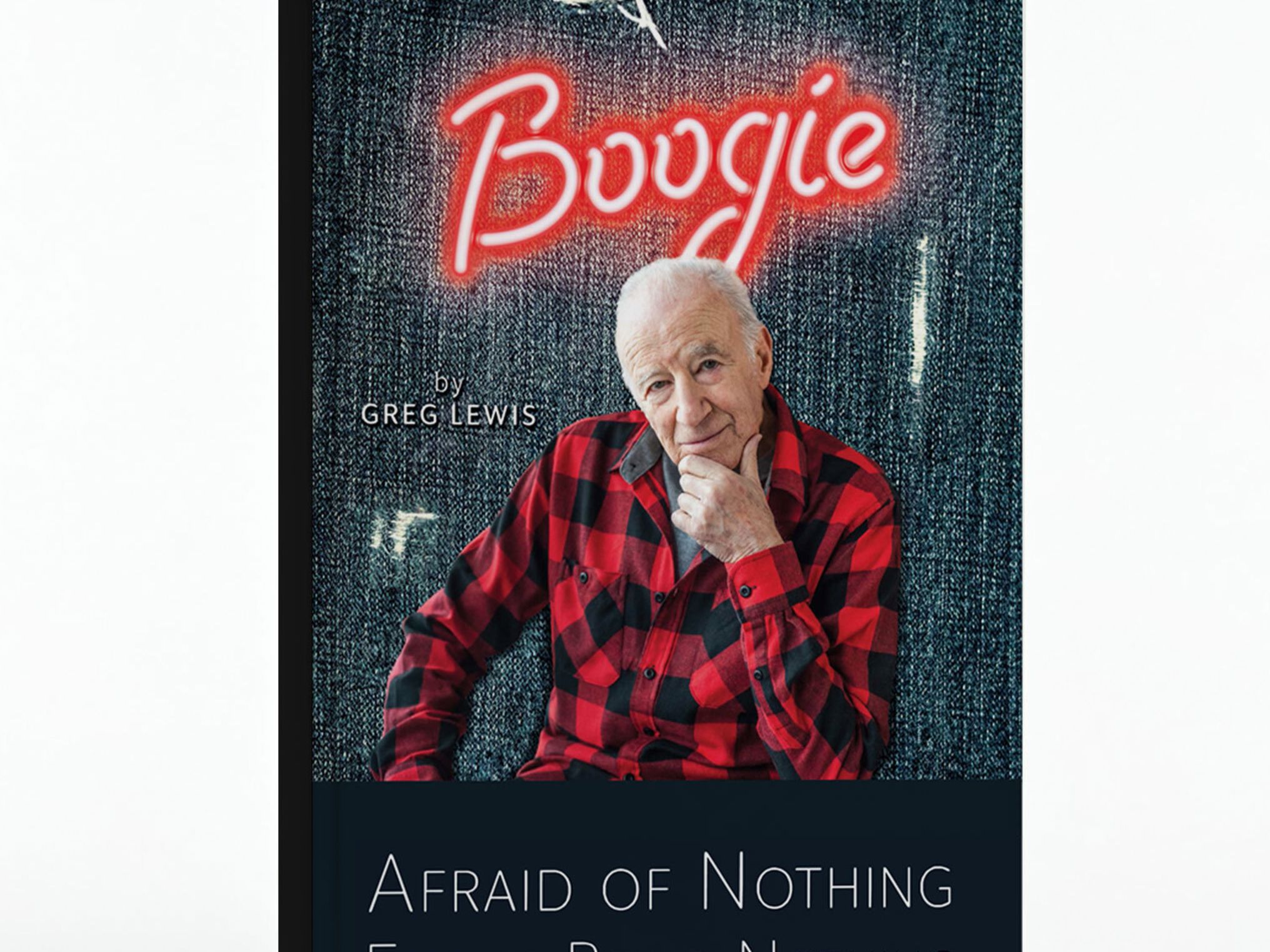

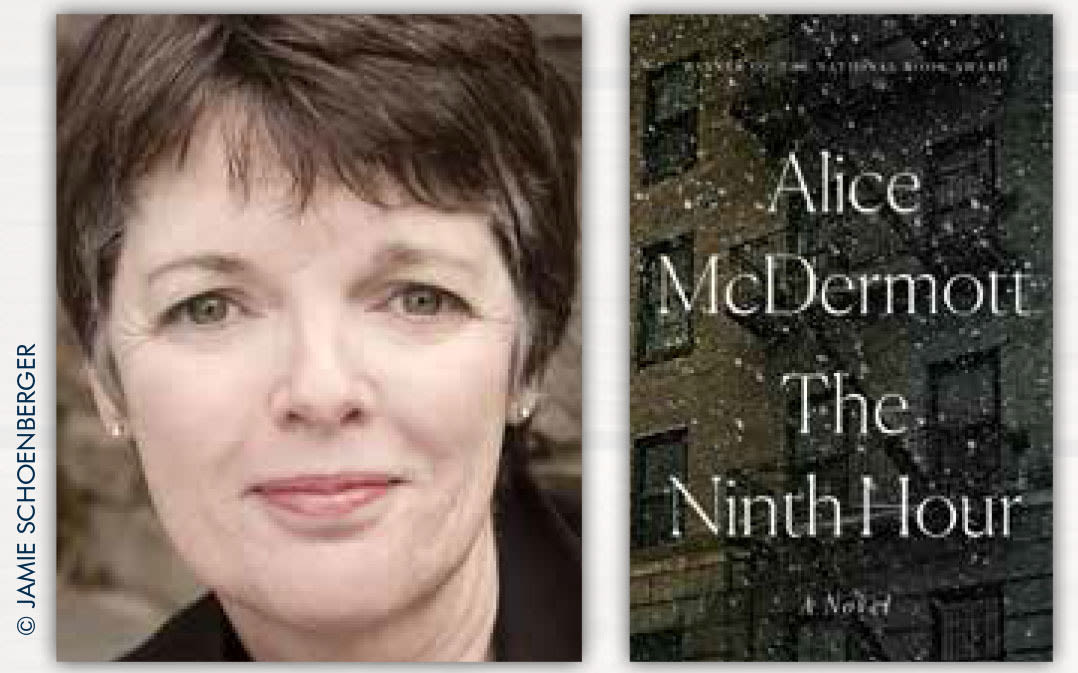

As you listen to Alice McDermott read from her exquisite new novel, The Ninth Hour, know this: the words she’ll be sharing aren’t those she originally intended to put on the page. “I didn’t start out to write about nuns,” says the National Book Award–winning author, who will open Aspen Words’ Winter Words series January 9. “They literally appeared and kind of elbowed their way into the entire novel.”

Instead, McDermott had planned to delve into the idea of substitutes in her eighth book, specifically U.S. Civil War surrogates—young men paid to fight in place of other young men. “I was drawn to the metaphorical implications of someone who gives a life in order that other lives can go on,” she explains. While a war proxy still plays a minor role in The Ninth Hour, McDermott veered course, exploring self-sacrifice and a life of service through the nuns of a fictional order, the Little Nursing Sisters of the Sick Poor, as she also traces the path of a family in early-20th-century Brooklyn.

That change in direction allowed McDermott to craft a richly complex portrayal of these oft-misunderstood religious women, who provided an important social safety net as they regularly tended to the infirm and the elderly. “After this nun showed up in the first chapter, she began to intrigue me,” McDermott says. “In the late 20th century, these women have been dismissed and made into clowns or witches, and treated as if they are homogenous.” Moreover, the self-sacrifice that so intrigues McDermott has morphed from a noble quality to a type of stigma, she believes: “I don’t know that we value that in the 21st century. We’re somewhat suspicious of that kind of total selflessness—we want to say, ‘Get a life.’”

Her research—in order to create a believable fictional world but not with the intent of writing historical fiction, notes McDermott—was revelatory. “I was just blown away by the tremendous work these women did,” she says, ticking off a partial list of accomplishments: providing aid to minorities and refugees, educating women, establishing hospitals (including the Mayo Clinic) and schools. “The patriarchal institution of the Catholic church does not support these women and give them the respect they deserve.”

McDermott humanizes her nuns, a hallmark of her approach to craft. As she notes, “Fiction insists on individual characters, never a stereotype. It’s the obligation of the writer to make each character unique and authentic.”

Really, the focus on nuns was not such a stretch for McDermott, who’s known for chronicling an Irish Catholic milieu throughout her novels. She says she generally doesn’t mind being typecast as such. What really gets her goat? “Being called a ‘quiet novelist’ drives me up the wall. I started The Ninth Hour with a suicide and an explosion and end it with a murder—what more do I have to do?” she laughs.

Since 1996, McDermott, who lives in Maryland, has taught writing to both undergrads and grad students at Johns Hopkins University, where she is the Richard A. Macksey professor of the humanities. She says teaching reminds her of commonalities (“you see young writers struggling, and you know it’s the same struggle whether it’s your first novel or your eighth”) yet sometimes compels her to reaffirm the power of literature. “I’ve been teaching long enough that I can see a difference,” she says. “Twenty years ago, young writers had more confidence that this literary art is necessary to the world. Sometimes it’s just a matter of saying it is important. I know my grad students could be in law school or getting MBAs, and it’s marvelous to me that they want to write literary fiction or be a poet. I remind them that whatever it is that brought them to the page is important and necessary.”

Currently McDermott has enjoyed getting back to her 9-to-5 writing routine after touring much of the fall for The Ninth Hour. The Druid Theatre in Galway, Ireland, has commissioned her to write a play. And she is working on a couple of novels simultaneously, as is her wont (“until one pulls forward,” she quips.) Very likely, she’ll end up with a story that’s different than the one she set out to write, a process she’s come to embrace. “When I was a novice, I found that rather dismaying,” says McDermott. “Now I find it delightful—the adventure of actually creating something through language.”

Alice McDermott appears at Winter Words Tuesday, January 9, Paepcke Auditorium, 6 p.m., Tickets $25, aspenwords.org