Celebrating 75 Years of Skiing on Aspen Mountain

Beneath a banner headline (“ASPEN GRAND OPENING”) stretching across the front page of the January 9, 1947, edition of the Aspen Times, mayor A.E. Robinson issued a proclamation, declaring that January 11—the dedication of Aspen Mountain’s Ski Lift No. 1—would be an official local holiday so citizens all could have a chance to ride a marvel of engineering he promised would “make Aspen the ski center of the world.”

The weekend-long festivities, drawing Colorado’s governor-elect, media from around the country, and visitors who had booked every room at the Hotel Jerome (prompting the paper to encourage Aspenites to open their homes to overnight guests), included ski races and jumping exhibitions, a ball and a fashion show, and a mountaintop ceremony honoring the many World War II veteran ski troopers of the US Army’s 10th Mountain Division who were instrumental in building the new lift and trails. But for many, a ride on the chairlift was the main event.

In a letter published in the Times, one Aspen resident recounted her first trip up the mountain as nothing less than transformational. “The vastness of the world that opened to view on all sides made me feel definitely awed and, and at the same time, highly exhilarated as the chair mounted higher and higher,” she wrote. “My heart was like to burst with the magnificence of the unfolding panorama—for the feeling inside was the biggest lift of all.”

As a passenger, she described watching raptly as a skier below seemed to dance across the snow.

“The grace, the perfect coordination, the rhythm were like a silent symphony as the figure lifted himself off the ground in absolute reverse turns and jumps ... [in] one of the most thrilling performances I’d ever witnessed,” she wrote, vowing to take ski lessons at the first opportunity.

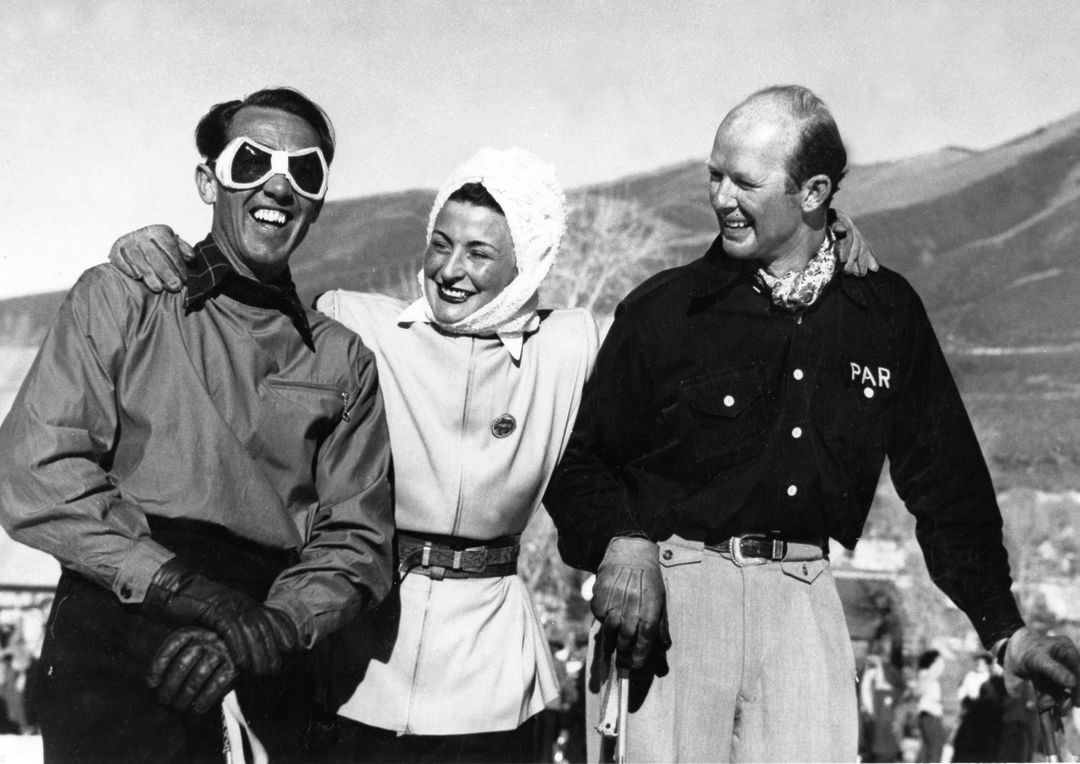

Friedl Pfeifer, Georgette Miller-Thiollière (a French alpine ski racer), and Aspen Skiing Corporation cofounder Percy Rideout at the grand opening of Ski Lift No. 1

Image: Knowlton Collection

Finding the Magic

Aspenites, of course, had been skiing the mountain long before Lift One. Since the 19th century, miners had been schussing into town from distant claims on “Norwegian snowshoes,” 12-foot wooden planks with steam-bent tips and leather straps cinched over work boots, while enterprising locals carved turns after making the climb on homemade setups fitted with sealskins or burlap, forerunners of uphillers today. But one pioneer in particular helped set the wheels of lift-served skiing in motion.

At the height of World War II in 1943, Austrian-born ski racer and instructor Friedl Pfeifer first saw Aspen Mountain on a trek from Leadville with the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division. Pfeifer, who had consulted on Sun Valley’s lift system and directed its ski school, wrote in his biography, Nice Goin’: My Life on Skis, that he felt “an overwhelming sense of my future before me.” He spent all his leave time in Aspen, hiking, skinning, and skiing Aspen Mountain and envisioning where the runs would be cut, “naturally with the contours of the mountain, blending with the meadows, gorges, and glades.”

Pfeifer returned to Aspen immediately after the war ended and partnered with the Aspen Ski Club to establish a downhill race: the Roch Cup, for André Roch, a noted Swiss skier and alpinist who had cofounded the club in 1936 and was the namesake of Aspen Mountain’s first cut run. Pfeifer formed a ski school, taking over the club’s Boat Tow (an early lift that used a truck engine and mining cables to transport skiers up the mountain in wooden toboggans), adding a rope tow for beginners, and spending much of his first winter (1945–46) teaching locals to ski.

Pfeifer knew a grander dual lift system to the 11,212-foot summit was key to unlocking Aspen Mountain’s full potential, so to accomplish that, he hired a lawyer to negotiate rights to mining claims, marshaled an army to design and cut trails, and found partners for a commercial venture (including Walter Paepcke, a Chicago industrialist who envisioned Aspen as a ski destination and cultural center and rallied investors), which was chartered in 1946 as the Aspen Skiing Corporation.

Walter Paepcke, Aspen mayor A.E. Robison, and Colorado governor-elect Lee Knous at the dedication of Ski Lift No. 1 on Jan 11, 1947

The giant bullwheel at the base of Aspen Mountain started spinning for the public on December 14, 1946. Chairlift rides were free on that day, and regular rates for “permanent residents of Aspen” were a fraction of the $3.75 daily ticket price (the equivalent of $53 today) for visitors. Lift One whisked riders 2,200 vertical feet to the top of what’s now the double FIS chairlift, well above the current unloading point of the Shadow Mountain chair (Lift 1A). Then a second single-chair lift (Lift Two, which opened a week later) brought skiers and sightseers to the summit, where the octagon-shaped Sundeck offered a simple menu, bathrooms, and a place to warm up after the 45-minute combined ride.

As word spread, newcomers to Aspen began arriving in droves via a Denver-to-Aspen ski train with dining and sleeper cars, or by air, landing on a gravel runway at an airstrip built by Paepcke. One of those was Klaus Obermeyer, a Bavarian skier who came to work in Pfeifer’s ski school in 1947 and that same year founded (and still runs, at age 102) skiwear company Sport Obermeyer. “The snow was incredible,” he says, remembering the first day he skied the mountain, 74 years later. “It was Champagne powder like you have in the Alps at 3,000 meters.”

For Obermeyer, accustomed to climbing mountains before descending them on skis, the chairlift was like “heaven had opened and the angels have come to kiss you.”

Skiing then was like a religion that brought all walks of life together to enjoy the outdoors in winter like never before, he says. “Skiing was shared with everybody,” from movie stars—Gary Cooper was one of the first, followed by Cary Grant, Lana Turner, and John Wayne—to dishwashers who rode lifts together, attracted to Aspen by a shared love of a sport that “gives you speed, zero Gs, and the beauty of the landscape.”

Jony Larrowe moved to Aspen in August 1950 (a year after Paepcke, with his wife, Elizabeth, founded the Aspen Institute and the Aspen Music Festival) with her first husband, Harry Poschman, who had helped build Lift One. Pulling up to their rental house on Main Street, Larrowe sized up the view and the serenity and thought, “This is where I’ll live; this is where I’ll die.”

The couple ran a ski lodge, and even as a mother of young children Larrowe skied as much as possible, preferring powder but also relishing the ride up the mountain. Aboard Lift One, she enjoyed watching wildlife and “loved the hum of the wheels” on lift towers. Later as a journalist and a poet, she rapturously recalled afternoons on Bell Mountain, when the last rays of sunshine tinted the snow golden before her eyes and cast shadows more stunningly than any artist could render.

“The views from the mountain were as important as skiing,” she says. “I ski because it’s a beautiful sport.”

It was also a lifestyle, Larrowe adds—a unique community in which everyone was united in the singular purpose of making the fledgling resort succeed, while also feeding their own passions. “It was a great community, bound by our love for snow and winter,” she says. “We had a camaraderie like I’ve never seen before and since. We belonged to each other.”

Norwegian slalom racer Stein Eriksen negotiates a gate at the 1950 FIS Alpine World Ski Championships; Eriksen won bronze at the event.

The '40s & '50s: Racing into the Future

Once established, Aspen seemed to have everything going for it: accessible terrain ideal both for recreational skiing and ski racing, great snow and weather conditions, an enthusiastic populace, financing through the Aspen Skiing Corporation’s board and Paepcke’s connections, and some of the world’s foremost ski experts to build, operate, and plan for the future.

In 1947, Dick Durrance, America’s most accomplished ski racer, was hired as the resort’s general manager. Along with Friedl Pfeifer, the Aspen Ski Club’s Frank Willoughby, and a few others, Durrance convinced the International Ski Federation to host a race on Aspen Mountain, a groundbreaking event that gave the fledgling resort visibility and credibility on the world stage.

Durrance’s hand-annotated map of the 1950 World Championships race course, which established Aspen on the world stage.

Image: Durrance Collection

The 1950 FIS Alpine World Ski Championships drew 1,500 spectators and teams from 14 nations, the first such race outside of Europe and the most prestigious in America to date. Without enough rooms available in hotels, local residents hosted ski racers and coaches in their homes, beginning a long-standing tradition that would further weave ski racing into the social fabric of the town.

Durrance, who was chief of race while also running the ski area and producing a film of the event, designed a thrilling men’s downhill course, funneling racers through a then-narrow Spar Gulch, forcing them over jumps made from mine tailings, and sending them plunging down the steep drop-off of Niagara before crossing four roads to the finish.

The races were a huge success, “cementing Aspen’s reputation as a mecca for international skiing and racing,” Pfeifer wrote in his memoir.

Aspen Skiing Corporation general manager Dick Durrance (in goggles), who helped bring the 1950 FIS Alpine World Ski Championships to Aspen, with U.S. Ski Team coach Toni Matt at Aspen Mountain.

Image: Durrance Collection

A passionate skier who had mapped trails at Sun Valley and Alta, Durrance (a 17-time national championship ski racer and 1936 Winter Olympian who died in 2004) was given free rein on Aspen Mountain—which, according to his son Dave, was the secret sauce. He designed several trails on the west side, which he made as wide as possible for sweeping open skiing. He planned trails around Chair Three (today’s Lift Three/Ajax Express) and “recognized the value of Bell Mountain,” where he did a lot of clearing, explains Dave, who adds that his father also carefully considered questions like, “How much of the mine tailings do you bulldoze to shape terrain, and how much do you leave to keep it exciting?”

In the 1950s, Aspen Mountain added four chairlifts, and Buttermilk (owned by Pfeifer and Art Pfister) and Aspen Highlands (owned by Whip Jones) opened to provide more options for skiers. But while the new venues appealed more to beginners and could help absorb growing numbers of tourists, Aspen Mountain retained its premier status as a destination for racing.

The Roch Cup became Aspen’s flagship prize, morphing over the years to encompass different disciplines and many races. When Aspenite Bob Beattie cofounded the World Cup series of ski races in 1967 and Aspen Mountain landed a spot on the circuit the next season, the event was billed as a Roch Cup championship, so coveted was the trophy. America’s Downhill, a challenging course with a 2,300-vertical-foot drop over its 9,000-foot length along the mountain’s western edge, was the only North American stop on the men’s World Cup tour for many years.

Athletes love racing on Aspen, says Johno McBride, who learned to race at the club and runs its alpine program after a storied coaching career with the Canadian and American men’s speed teams. “Aspen Mountain has a real-deal downhill and phenomenal giant slalom and super G. It’s a world-class race venue with pitch and variable surfaces.”

Noting that its high elevation helped Aspen Mountain successfully pull off the 2017 FIS Alpine World Cup finals during unseasonably warm conditions, McBride hopes that international ski racing will someday return to its rightful home.

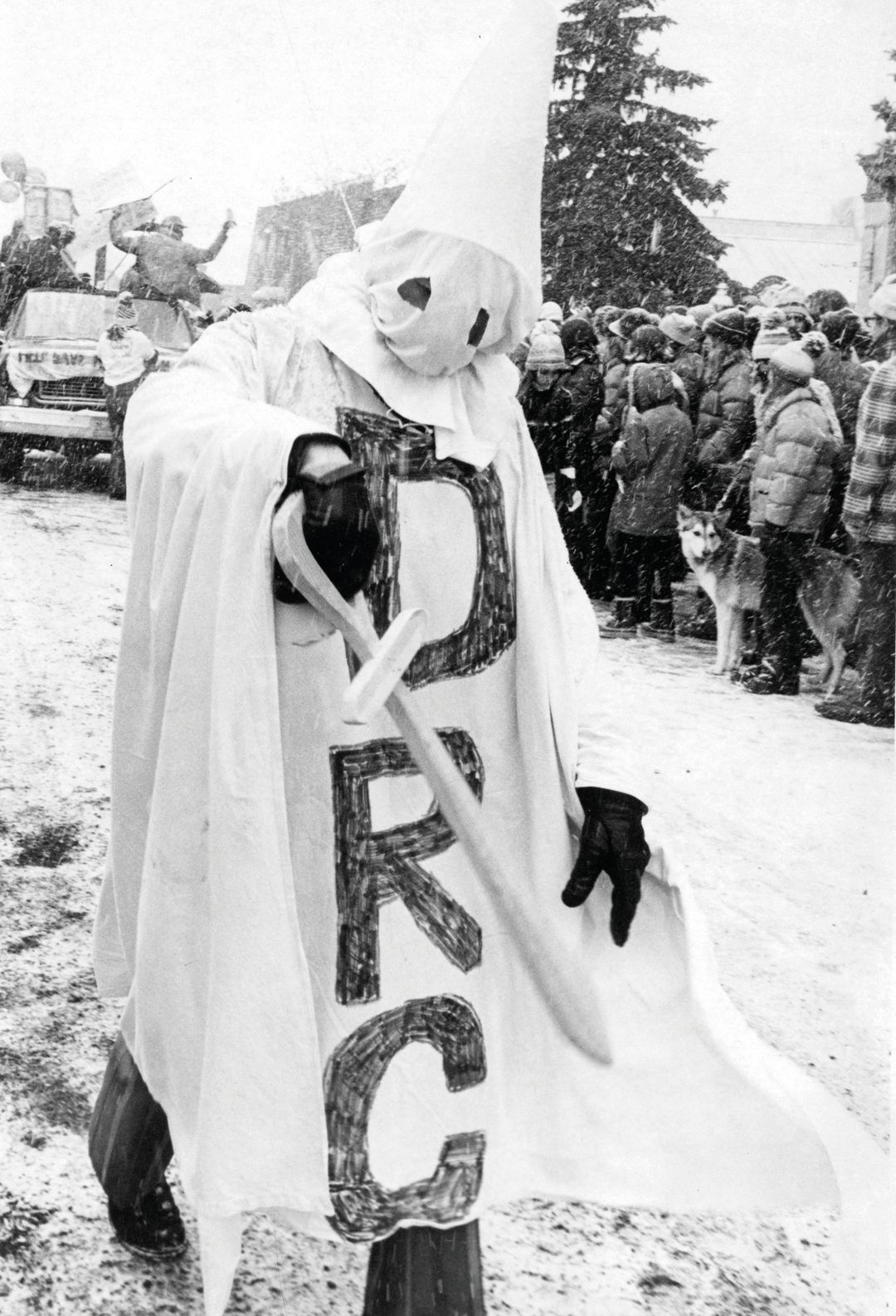

A protester marching in the Wintersköl Parade in January 1976 registers popular discontent with Aspen Skiing Corporation president D.R.C. Brown, after the company stopped honoring its three-resort ski pass on Aspen Mountain to curb the unruly behavior of locals.

Image: Aspen Times Collection

'60s–'80s: Star Wars and Pass Wars

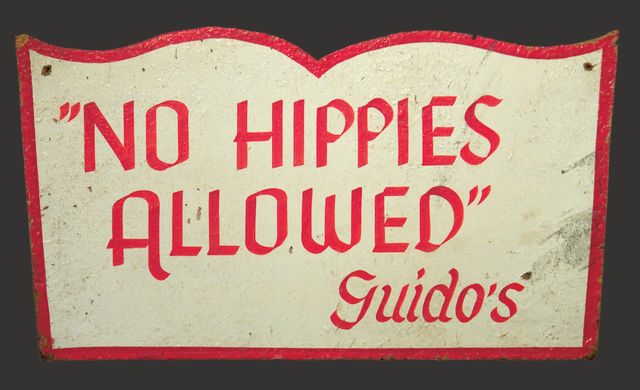

As social upheavals of the late ’60s and ’70s rocked the nation’s urban centers, young idealists and hippies (in 1965 the Denver Post dubbed them “skiniks”) came, and stayed, to revel in the free-spirited mountain life Aspen offered.

Like many longtime Aspenites, Gerry Sullivan has almost fairy-tale-like memories of his first years in town. Arriving in summer 1970 intending to pass time outdoors while waiting for his Vietnam draft number to come up, Sullivan’s entrée to Aspen seemed ordained by the stars: he was invited to the Paepckes’ now-renowned Aspen Music Festival his first night, found a campsite to call home, spent the summer hiking, and landed a winter job with a ski pass at, appropriately, the Magic Pan restaurant. On opening day that winter, “all of Aspen Mountain was open and waist deep,” he says. “Hanging Tree to [Chair] Three on my Rossi Strato 207s was my first run.”

By the time Sullivan and so many others like him had discovered Aspen, the population had more than doubled over the previous decade, to 2,437. It jumped another 51 percent by 1980. Meanwhile, slopeside crash pads for locals were razed for luxury condos and increasingly extravagant second homes, as Aspen earned a reputation as a wintertime playground for Hollywood celebrities, Wall Street tycoons, and fashionistas who came to Aspen not just to eke out a living and ski, like Sullivan and his crowd, but to spend lavishly in town and be photographed on the slopes. Skier visits rose dramatically, too, surpassing the 1 million mark in the mid-1970s.

Ski bums like Sullivan responded to the inevitable clash of cultures in stride: working nights to ski all day, earning just enough to maintain the lifestyle, and getting creative with housing (Sullivan once lived in a barn). On the slopes, he and his ski buddies figured out how to dodge crowds and avoid long lift lines by bribing lifties with beer, pooling funds to hire private instructors, and taking to the backcountry during the busiest hours of the day.

Leading the Aspen Skiing Corporation (which locals dubbed “the Ski Corp”) during this period of unprecedented growth and change was Aspen native D.R.C. “Darcy” Brown, who had happily leased his family’s mining claims to Pfeifer in the 1940s to ease the way for Lift One because he was tired of walking uphill to ski. During Brown’s tenure as president during the ’60s and ’70s, the company grew from 25 to 1,200 employees as it acquired Buttermilk, Snowmass, and Breckenridge. But the product—skiing—in some ways had become a victim of its own success. In the mid-1970s the Ski Corp stopped honoring its popular three-area local pass on Aspen Mountain to deter raucous local passholders from ruining the experience for visitors who were paying a premium to ski.

A sign (hand-painted by ski instructor Sepp Uhl) that hung in the window of Guido’s Swiss Inn in 1965, attesting to the culture clash that played out on the streets and slopes of Aspen during the tulmultuous decades of the 1960s and ’70s, when annual skier visits on Aspen Mountain surpassed the 1 million mark.

“Locals were a bunch of unruly punks,” says Tony Vagneur, who patrolled on Aspen Mountain in the ’70s. “We had trouble clearing them out at night when they were smoking dope and hanging out.”

As Aspen’s cachet grew and developers bought up local real estate, corporate America also saw opportunity in the Ski Corp. Twentieth Century Fox bought it in 1978—reportedly with profits from Star Wars—leading to Brown’s resignation and 15 years of shuffling among various investors. The first was Marvin Davis, a Denver-based oil tycoon who bought 20th Century Fox in 1981 and changed the Aspen-based holding's name to the Aspen Skiing Company (or “SkiCo,” as it’s known today), followed by the Crown family of Chicago. The various owners also made major improvements. On Aspen Mountain, snowmaking was added along with modern grooming equipment. Aspen’s first high-speed quad went in at Lift Three/Ajax Express in 1985.

Elizabeth Paepcke and Friedl Pfeifer ride the Silver Queen Gondola (which reduced the base-to-summit ride time from 45 to 15 minutes) at the lift’s dedication on January 16, 1987.

Most transformational was the Silver Queen Gondola, installed in 1986, which cut the base-to-summit ride time from 45 to 15 minutes and changed how the mountain skied, including facilitating top-to-bottom laps and making the open, gentle runs off the summit more accessible to less advanced skiers or those who didn’t ski at all and just wanted to partake in the social scene at the Sundeck.

But with the upgrades came price increases and sticker shock. By 1980, when a season pass soared to $300 (the equivalent of $1,007 in current dollars), Aspen Mountain was back on the three-mountain season pass, but passholders paid a $10 ($33.57 today) daily validation surcharge to ski there during busy periods, like the Christmas holidays, rankling locals. By the end of the decade, an Aspen Mountain validation sticker was required for nearly half the ski season. When SkiCo doubled the Aspen Mountain validation fee from $10 to $20, “the community went ballistic,” recalls Jeanette Darnauer, who was the company’s PR director at the time, hired to improve community relations. Locals formed an issue group, circulated a petition, and demanded change at raucous public meetings, but upper management refused to budge on pricing. Darnauer advised her bosses that the company needed to do something to assuage the community, and locals channeled their frustrations into an advisory committee that championed the two-day-a-week pass, which remains one of the most popular pass products today.

A powder day on Aspen Mountain.

Image: Jeremy Swanson

Rediscovering the Magic

By the dawn of the new millennium, Aspen Mountain's reputation as a haven for the rich and famous stretched from base to summit. At the bottom of the mountain, the five-star Little Nell Hotel replaced a locals’ favorite après-ski bar of the same name in the late 1980s. At the top, the membership-only Aspen Mountain Club made its home in a renovated Sundeck just after Y2K, an exclusive enclave for celebrities and the monied who ascended the gondola not to ski but to hobnob in the latest ski couture.

In some ways, it was inevitable. Pass prices had increased significantly in the early ’90s when the Aspen Mountain surcharge finally was eliminated, and marketing catered to an ever more affluent audience. SkiCo’s former PR director Jeanette Darnauer, who left the company in 1988, opines (reflecting local sentiment at the time) that the branding of the early ’90s, which focused not on skiing but on idyllic snowy imagery, “was elitist, arrogant, and wasn’t reflective of the positive ski and community experience we had.”

Then in 1993, the Crown family, which had bought a half interest in SkiCo eight years prior, became sole owners. Shortly after, the Crowns bought Aspen Highlands, adding a fourth local mountain to the resort, and hired Pat O’Donnell, the former CEO of Patagonia, bringing strong environmental, values-driven credentials to remake SkiCo’s corporate culture. And he was a snowboarder.

That may explain partly why, on April Fool’s Day 2001, SkiCo lifted its snowboarding ban on Aspen Mountain, the last of its four mountains and the last ski area in Colorado to do so. Some diehard skiers protested—Ajax’s steep, narrow bump runs weren’t conducive to single- and double-plank turns at the same time, they argued. For others it was yet another iteration of the “skiniks” that had descended on Aspen in the ’60s and ’70s: baggy-pants-wearing, scruffy millennials who raised hell zooming across the mountain on the alpine equivalent of skateboards—the new rebel class—rubbing baggy-jacketed shoulders with the Bogner- and Prada-clad clientele riding the Silver Queen to lounge at the Aspen Mountain Club.

Apart from welcoming snowboarders, Aspen Mountain arguably hasn’t advanced as much during the past 20 years as it did during its first half century. But while SkiCo’s other three mountains embraced what many in the industry deem to be the youthful future of skiing by adding freeride terrain, infrastructure, and competitions, Aspen rekindled a flame from its past. In March 2017, Aspen Mountain staged the men’s and women’s FIS Alpine World Cup Finals, the first U.S. resort to host the event in two decades and a vindication of sorts after losing a bid to host the women’s World Cup to Killington, supposedly for lacking a world-class finish and base area.

The coronavirus pandemic, ironically, also nudged Aspen back toward its early skiing roots. When the governor’s public health order shut down all of Colorado’s ski lifts in March 2020, SkiCo not only allowed locals to skin up and ski down its mountains, but encouraged them—notably by grooming one run daily for the uphilling crowd.

In an open letter published on SkiCo’s website that month about what to expect the following season, CEO Mike Kaplan announced pared-down services, none of the usual parties and events, and an opportunity for everyone, SkiCo included, to hit the reset button on skiing, and skiing in Aspen in particular. “I’m looking forward to refocusing on the core of what this sport is all about, what this place enables: a chance to connect deeply—with nature, with our physical selves and movements, and even with our sense of purpose and our roles in society,” Kaplan wrote. “No doubt, next ski season will be more of an old-school experience, but that could also translate to less noise, fewer distractions, and, hopefully, more meaning.” In a follow-up letter at the height of the pandemic, he reiterated that while everything else in the world seemed uncertain, “skiing feels more vital than ever,” recalling the spirit and promise of 75 ski seasons ago, when Lift One first started spinning.