Glenwood Glory

The hotel’s facade and courtyard, now and then

ON JUNE 10, 1893, with 12,000 yards of Axminster carpet laid, seven miles of electric wiring installed, 10 acres of plaster applied, 2,000 rosebushes planted, 300 tons of ice crushed, and 500 invitations issued, the Hotel Colorado opened to the world. Lined up on a rail spur just west of the hotel were dozens of private train cars—the Lear jets of their day—each one more opulent than the next. Inaugural events for the hotel included morning swimming contests in the hot springs pool, followed by afternoon polo and horse races.

At sundown, guests were treated to a sparkling light and water display in the central courtyard, featuring an electrically illuminated Florentine fountain that sprayed 150 feet into the sky between the hotel’s twin red-roofed bell towers. Following an elaborate banquet and ball, many of the guests plunged into the pool. Whether or not they changed into their bathing attire is unknown.

What drew these highbrow travelers to Glenwood Springs from faraway places was the vision of Walter Devereux, a Princeton-educated geologist–

turned–silver baron who saw in Glenwood Springs the opportunity to build a luxury hotel and European-style resort and spa that he called the Hotel Colorado. Hailed as the “finest resort hotel between the Great Lakes and the Pacific” and designed to replicate Rome’s Villa de Medici, the hotel was surrounded by formal gardens, green lawns, and ornate fountains on the north side of the Colorado River. Its imposingly formal brick-and-sandstone facade loomed like a fortress over the rugged frontier valley.

Inside, thousands of bulbs—some small and twinkly and others big and brilliant—bathed ornately decorated gathering spaces in then-modern incandescent light. Perhaps one of the most unique features on the hotel’s first floor was an interior pool, measuring 24 by 36 feet, stocked with fresh trout, and continuously refreshed by a gushing 25-foot waterfall cascaded over a panel of illuminated Colorado glass. A guest could simply grab a fishing rod and a stiff drink, pull up a comfortable chair, and marvel at the extreme ingenuity required to create a tumbling mountain stream inside an Italianate villa.

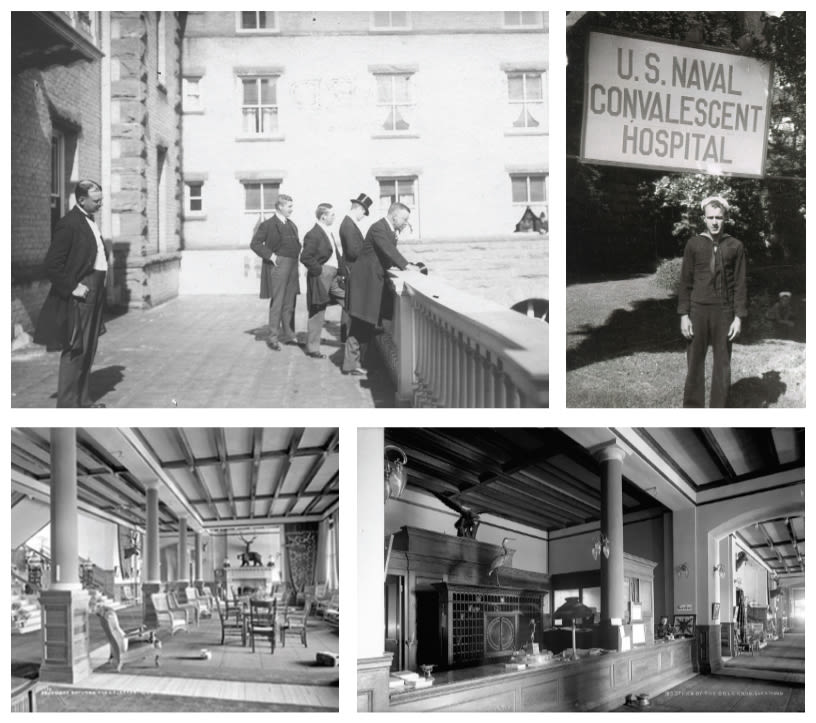

Clockwise from upper left: Theodore Roosevelt addresses a crowd of hotel guests and locals gathered in the courtyard during a 1905 stay in the hotel’s Presidential suite; a US Navy sailor outside the hotel (circa 1943) when it was repurposed as a convalescent home for wounded World War II veterans; the hotel’s front desk and lobby in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Until the beginning of World War II, the hotel hosted many well-known figures, including socialite and Titanic survivor Molly Brown (for whom a suite is named), Diamond Jack Alterie and his coterie of Chicago gangsters, and a slew of politicians including Presidents Taft and Hoover. In 1905, Theodore Roosevelt and his staff turned the hotel into the western White House for three weeks while the rough-riding POTUS journeyed into the surrounding high country to hunt for bear.

In 1943, the hotel and surrounding property were leased to the United States Navy for use as a hospital for wounded World War II sailors and soldiers. To ensure its complete sanitation, everything—from furnishings and carpet to drapery and dishware—was removed. Bannisters, paneling, and even flooring were stripped bare of elaborate finishes. Fireplaces were plastered over, mantelpieces ripped out, and marble, deemed too porous to be sanitary, was removed from every bathroom. Over 6,500 patients stayed at the hospital during its 33 months of operation, their battle-scarred bodies and minds rejuvenated by the property’s hot springs, bright sunshine, cool mountain air, and endless recreational opportunities.

Following the war, the hotel struggled to reinvent itself as the Grande Dame of the Rockies. At the other end of the Roaring Fork Valley, Aspen was coming to life as an international ski resort. Airplanes usurped transcontinental trains as the most efficient—and luxurious—method of travel. In 1954, a Dartmouth grad–turned–ski bum named Ralph Melville bought two lots at the base of Aspen Mountain for $2,000 and began building a European-style ski lodge. Opened in time for Christmas that same year, the Mountain Chalet had three “usable” rooms. By the end of ski season, Melville had added another six. Between 1958 and 2003, Ralph, Marian, and their eight children had expanded the lodge to five floors and 59 rooms.

The Hotel Colorado’s Craig Melville; in 2018, the Melville family, owners of Aspen’s iconic Mountain Chalet, purchased the Hotel Colorado and initiated a $10 million rooftop-to-courtyard historic renovation.

IMAGE: RYAN DEARTH

In 2018, two years after the family patriarch died at the age of 90, the Melvilles learned that the Hotel Colorado, in dire need of a renovation after 125 years, was for sale. Despite a general family policy to “never channel our father,” says son Craig, “we knew Papa would be in favor of this.”

In hindsight, their timing in purchasing the property couldn’t have been worse. The Grand Avenue Bridge project, an almost 24-month closure that disrupted travel through downtown Glenwood Springs, had just wrapped up, a necessary improvement that the hoteliers took in stride, says Craig with characteristic optimism.

“Our initial goal was to improve weekday business, so we began renovating the conference rooms because we thought that would boost group sales,” he explains, noting that updates to the hotel's meeting spaces and ballrooms were completed in 2019. “Then Covid hit, and there was no group business.” The Grizzly Creek Fire closed Interstate 70 for 13 days in August 2020, at the height of the summer tourist season. After selling the Mountain Chalet in 2021, the Melville family persevered with the Hotel Colorado, their faith in the project never wavering even as world events shook the hospitality industry to its core.

This summer, California-based Planning, Design & Application Inc. (PD&A) is overseeing the first phase of a $10 million bell towers-to basement historic restoration that will wrap up by the end of the year.

The Hotel Colorado’s main lobby, a.k.a. the living room of Glenwood Springs

IMAGE: RYAN DEARTH

What guests will notice most when they enter the newly remodeled hotel is the overwhelming sense of lightness that permeates all public spaces. Gone are the poorly lit corridors, mauve carpets, and dark moldings. In their place is a blue-and-white color scheme, an homage to the Naval hospital, with period lighting that illuminates the revitalized pine floors, original stairwells, and ornate wood paneling throughout the hotel. Construction drawings made during the Navy’s occupation of the building will be reproduced in blue, framed, and hung in each room. Historic furnishings are being catalogued and will be displayed in corridors or in one of the hotel’s several specialty suites. Unique antiques and artifacts, like the hotel’s original switchboard, will be moved to the Hall of History, a museum located in the basement.

Remaining relevant in a post-pandemic world is a challenge for hoteliers managing vintage properties like the Hotel Colorado. For most travelers, amenities like no-touch check-in and checkout, smart room technology, and uninterrupted access to a high-bandwidth internet connection are far more important than luxuries like a 200-square-foot bathroom with a jetted tub. In the world of brand hotels, meeting and exceeding these expectations is a no-brainer. Historic hotels, on the other hand, cater to a different clientele, and that’s where the opportunity to create a renovation plan on a grand level is so unique, says PD&A founding partner Karen Struck.

“This is about a story, not a trend,” she asserts. “Guests come here to be entertained by history. Our job is to take a thoughtful approach to revitalizing this iconic 1893 hotel, showcasing its splendor and welcoming today's travelers who are seeking authentic travel experiences with modern conveniences."

While larger hotel chains typically implement a remodel or redesign to fulfill a certain marketing goal or corporate rebranding, a commission like this is much more challenging, adds Struck. “This is a once-in-a-lifetime project,” she says. “We feel honored to be both here and working in this way.”

A sneak peek at a renovated room’s updated décor.

IMAGE: RYAN DEARTH

Their approach and process to redesigning each room “is not about creating a typical hotel guestroom package,” says Struck’s co-partner Mike Russell. After measuring each of the rooms and suites by hand (each was subtly unique and no original construction drawings existed), the designers conducted a series of spatial planning exercises on a collection of different rooms to determine how each type would lay out. A “look” inspired by the Villa de Medici was then developed—including marble-topped desks, Italianate nightstands, embroidered motif headboards, Victorian-style mirrors and knobs, and exposed brick—that would work in any of the hotel’s 142 rooms. The designers referenced old photographs of the hotel to illustrate how their design would speak to the story of the place.

“It’s not a signature design,” says Struck, “but we think it’s relevant for visitors in the 21st century. Our approach has focused on gathering and then exposing all its best parts with an updated design that makes guests feel alive, technically supported, and surprised by how utterly cool it really is.”

While the prevailing emphasis is on clean lines with a neutral and modern palette, specialty suites are more period-correct, with the addition of color and unique artifacts from the time of the hotel’s heyday. “Many historic hotels tend to go overboard on modern design, and it doesn’t always work,” says Hotel Colorado president Christian Henny. “What we’ve created here is an environment that feels fresh and bright while letting the vintage furnishings and fabric take center stage.”

Under its new ownership, the hotel rejoined the Historic Hotels of America, a group of iconic hotels across the country that, in Colorado, includes The Broadmoor and the Hotel Boulderado. It’s a move that Henny says is good for business. “There’s so much to do in and around Glenwood Springs,” he adds. “We want to be the choice that travelers make to enjoy a piece of this region’s unique history.”

Then there’s the unique place that the Hotel Colorado occupies in the hearts and minds of locals. “People really care about this hotel,” Russell says, recalling the interviews the design team conducted throughout downtown Glenwood Springs as part of their research. “They’re passionate about it,” adds Henny. “This lobby is Glenwood Springs’ living room. The restoration is a way to honor that relationship.”

It’s a consideration not lost on the design team.

“As we honor the past, we are also thinking about the future and the ways in which we can bring the Hotel Colorado back to what it was for the guest of the 21st century,” says Struck. “So many things change, but we’ll dress it beautifully so when you walk in from any direction, you’ll feel a sense of amazement and connection.”

How connected? All the way back in time to that day in 1893, when the Hotel Colorado opened its doors to the world—and the world arrived, in wonder.