Nuestro Futuro

Image: Karl Wolfgang

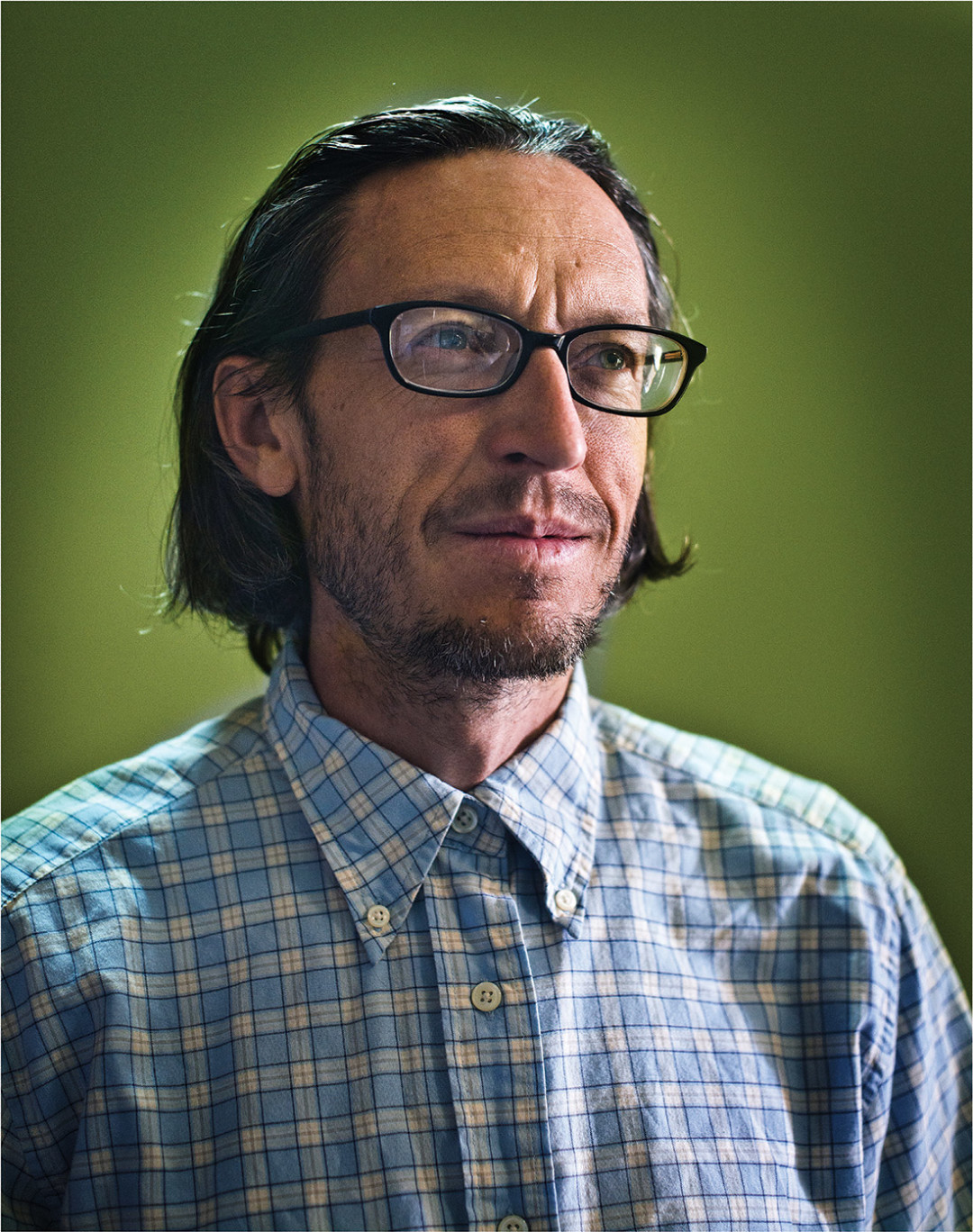

ELISABET ROJAS leads her preschool class in a minute-long meditation. She uses a large plastic toy that expands and contracts to demonstrate how to fill the lungs with a deep breath, and she begins the exercise by sounding a chime. Little lungs fill with air, then exhale. “It helps them to calm down and focus,” she says.

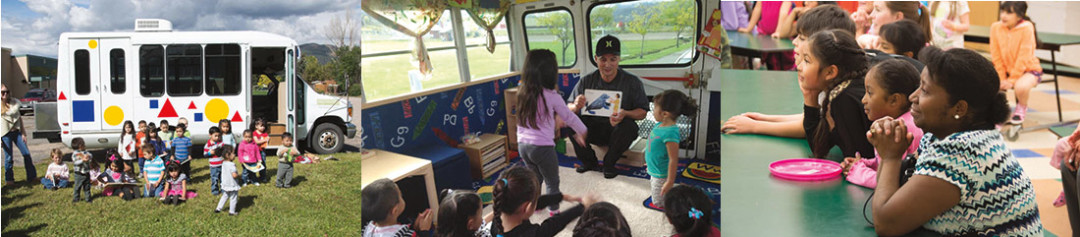

The students Rojas is teaching are not in a traditional classroom. They’re in a retrofitted school bus known as El Busesito. For most of the children, “the Little Bus” is the first classroom they’ve ever been in, and it’s a key component to the considerable success of the Valley Settlement Project, a nonprofit bringing pre-K education to children in low-income families and adult education to their parents in the Roaring Fork School District. Rojas, originally from Granada, Spain, is El Busesito’s director and lead teacher.

Elisabet Rojas, Director & Lead Teacher for The Little Bus

Image: Karl Wolfgang

In many ways, El Busesito is way cooler than the average preschool. It’s on wheels, for starters, and is equipped with bright blue carpeting, electric yellow walls, a library, toys, and all kinds of tools for learning. Classes are small—eight or nine kids attend two-and-a-half-hour sessions twice a week—and they are offered two times a day, four days a week, during the school calendar on three buses that travel to low-income neighborhoods from Glenwood Springs to Basalt. The mobile schools are bilingual; teachers speak mostly Spanish but try to do activities and instruction in English. The curriculum addresses language, math, literacy, cognition, and social and emotional development. In the 2014–15 school year, the three Busesitos served ninety-six students.

Before El Busesito came along, only 1 percent of kids from the low-income neighborhoods in the Roaring Fork Valley surveyed by Valley Settlement had access to preschool education. As a result, those children were entering kindergarten severely deficient in language and social skills. Since Latino kids make up 55 percent of the Roaring Fork Valley public school population—far from a minority—the entire school system felt the impacts.

Kenia Pinela, Family Coordinator

Image: Karl Wolfgang

At the end of the 2014–15 school year, El Busesito had forty-two “graduates,” its largest class yet. “The feedback we’re getting from the school district is our kids are walking in the door ready to learn,” says Valley Settlement’s Amanda Tamburro-Friend, a former preschool teacher with more than a decade of experience in the public school system. “They’re ready for the job of kindergarten, but more than that, our families are more engaged, which is going to make their kids more successful.”

Engaging parents is a big focus for Valley Settlement. The nonprofit is built on a two-generation model, meaning it also offers programming for the parents of the children it serves. Adult Valley Settlement programs include Family, Friends and Neighbors, a child-care training course based on state licensure requirements that provides a network of childcare for working moms, and Learning with Love, an infant-toddler program for ages newborn to three. In addition to two classes a week (locations move with Los Busesitos around the valley), Learning with Love teachers visit families twice a month in their homes as part of Parents as Teachers, an evidence-based curriculum that focuses on parent coaching, childhood development, and family well-being.

“The project really proceeds with this idea that even if you improve the educational opportunities for kids, without simultaneously addressing the needs of the parents and the homes these kids are going to go back into, you’re not really maximizing what you’re doing on the school side of the equation,” says Jon-Paul Bianchi, associate program officer at the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, one of the United States’ largest philanthropic foundations and an organization that helped finance Valley Settlement.

Jon Fox-Rubin, Executive Director

Image: Karl Wolfgang

The need for Valley Settlement had been staring local communities in the face for some time. While Aspen is a playground for jet-setters and point-one-percenters, a place where a second language might come in handy to, say, decipher the label on a bottle of vintage French wine, it’s a different world right down the road in the communities of Basalt, Carbondale, and Glenwood Springs. A language barrier is only one of the many challenges faced by hundreds of families living in poverty and isolation all across the Roaring Fork Valley.

That hiding-in-plain-sight problem led the Manaus Fund, an organization dedicated to social justice that George Stranahan founded in 2005 and from which Valley Settlement was born, to try to come up with a solution. Boosted by a planning grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Manaus’s bilingual community organizers spent ten months knocking on doors. They interviewed more than 300 families in twenty-five neighborhoods from Aspen to Rifle about their lives.

“Our goal is to meet our families where they’re at, and to do this with them, not for them. We focus on the parents as much as the children,” says Jon Fox-Rubin, executive director of Valley Settlement. “Valley Settlement Project is a process based on families telling us what they need. The response to those needs defines our program development.”

Katie Langenhuizen, Director, Learning With Love

Image: Karl Wolfgang

The organizers learned that 42 percent of the parents surveyed hadn’t made it past the sixth grade. Some were illiterate: how could they learn English when they were unable to read and write in their own language? Transportation was also a barrier. A household’s only driver was almost always the primary wage earner, leaving moms stranded at home. The public bus system is too expensive for low-income families to use every day. Mothers said they felt disconnected from the schools and were afraid to go out into their communities.

“I was caught off guard by the number of neighborhoods I didn’t know existed. It’s a community that’s hidden,” says Katie Martin Langenhuizen, who interviewed dozens of families as Valley Settlement’s Learning with Love program director. “Every single parent I talked to wants to learn English, and they want their kids to get educated. But in order for someone to feel part of the community, they have to have confidence to engage with that community. That’s our goal: to give them that footing, that confidence.”

El Busesito is free for children, but their parents are required to meet volunteer obligations and attendance requirements in order for their kids to stay enrolled. “It’s important to engage the families, and for them to have this commitment to be involved with the school,” Rojas says. “Our hope is they’ll continue with that commitment in elementary school and stay involved with their child’s education in the future.”

Alejandra Magaña Principal, Lifelong Learning

Image: Karl Wolfgang

WHEN ALEJANDRA MAGAÑA first moved to the Roaring Fork Valley from Michoacán, Mexico, three years ago, she was afraid to leave the house without her husband by her side. Ricardo Magaña worked two jobs and was often gone from noon until well after midnight. What Alejandra experienced was more than just culture shock: like many immigrant families who come to the Roaring Fork Valley, she felt vulnerable. She didn’t speak any English, was totally unfamiliar with American culture, and was fearful of white people. She had no means of transportation and didn’t know anyone outside of her immediate family. She was unable to help her seven-year-old son with his first grade homework. Learning English seemed impossible. Even though she lived in a neighborhood with other immigrant families, she didn’t know whom to trust. So she passed the hours cleaning and taking care of her three-year-old daughter, Alexa, waiting for her son and her husband to come home.

Then she met Eloisa Duarte.

Duarte wears her honey blond hair in long braids, both wrists adorned with thick beaded bracelets, like cuffs on a female superhero. Her green eyes shine bright, as if she’s lit from within, possessed by a warmth and energy that’s uncontainable. She is articulate, and her English is strong. She talks incessantly, relying heavily on metaphors, and tends to say “long story short” a lot, even when she is only getting started. It’s hard to imagine that she was once afraid to leave her home and embarrassed to go into her son’s school, because she couldn’t speak English. She moved to the Roaring Fork Valley (which she calls “mountain paradise”) from Sonora, Mexico, in 2007 to join her husband, who was working for the Aspen Skiing Company. She spent her first four years holed up in the home, taking care of her children.

But in three short years, Duarte became fluent in English, earned her GED, and rose through the ranks of Valley Settlement’s adult programming, from Parent Mentor volunteer to Parent Mentor director to director of Lifelong Learning, which offers adult education in Spanish to help build literacy and GED, ESL, and job skills. All of those programs have grown significantly, in large part thanks to Duarte, who’s now a veritable poster child for Valley Settlement, a success story who can knock on doors and say, “I did it. You can do it, too.”

For her, it all began when she found a flier soliciting volunteers for Valley Settlement’s Parent Mentor program in 2012 and decided to give it a try. She was placed in a third grade class at Crystal River Elementary, and from the start it was a good fit. “At first I wasn’t able to speak English, but the teacher was so kind to me, it gave me the confidence to try,” Duarte says. “When someone else believes in you, you start to believe in yourself. Schools are nests of hope.”

Amanda Tamburro-Friend

Early Childhood Specialist

Image: Karl Wolfgang

Parent Mentors volunteer ten hours a week, assisting in elementary school classrooms across the Roaring Fork School District. The program’s effectiveness is twofold: It gets the parents involved with the schools, and it enables them to learn English along with the kids in an environment that’s a lot less daunting than trying to learn on their own. It also helps teachers whose resources are maxed out and whose students often don’t speak any English. Having a native speaker to assist is a huge asset.

“Before I was just a mom at home, cleaning and waiting for my kids to come home and tell me stories, and now I have my own stories to share,” Duarte says. “Now I start falling in love with my community. I’m able to connect with other families. It doesn’t matter—Anglo or Latino—I’m so proud to learn from kids.”

The Parent Mentor program has grown from thirteen mentors in 2012 to sixty-nine mentors volunteering in six valley elementary schools in the 2014–15 school year.

“When I became a coordinator, it was easy to find women like me. Immigrants are thirsty to belong, to be part of the community, and to be proud of the community,” Duarte says. “We bring them from the shadows into the light and show them they can be diamonds.”

RICARDO MAGAÑA cues up a video of Alejandra on his iPhone. She is standing behind a podium in a large and opulent room, speaking at the Colorado capitol in front of a sizable crowd—in English—about the Valley Settlement Project. The Magañas’ five-year-old daughter, Alexa, sits in Ricardo’s lap, looking on in a pretty purple dress and sparkly shoes.

“The audio isn’t great, but it gets better in just a second,” he says, unable to contain his pride. “At the beginning, she wouldn’t even come to meetings at school; she was so afraid. I thought she would want to go back to Mexico. And look at how far she’s come. It’s been a great change.”

The change happened when Alejandra met Duarte and became a Parent Mentor in 2013, after she’d been living in the Roaring Fork Valley for a year. “I was really afraid, but Eloisa encouraged me to do the things I thought I was not able to do. She convinced me that I could do it,” Magaña says.

It was less scary than she thought. “The school is a great way to start,” she says. “The kids are so compassionate with you. The teachers are the perfect teachers for us. You learn how to teach, how to work with kids, and how to support your own kids.”

Like Duarte’s, Magaña’s success and English acquisition were rapid. In her second year with Valley Settlement, she became principal of Lifelong Learning, helping Duarte pioneer new programs like literacy classes in Spanish offered in a community room in her neighborhood. “I have students who could not read their daughter’s name,” Magaña says. “We are now offering classes in Spanish, so they can learn. I understand the problems, and now I know we can jump those problems to get to our dreams.”

Image: Karl Wolfgang

That type of reaction has been uplifting for everyone involved in Valley Settlement, not just the participants but also the people who helped to create it. “It’s my dream job, because I’m working with very complex problems and seeing tremendous progress in our community,” says Fox-Rubin. “We’re also helping other organizations, such as the Vail Valley Youth Foundation’s work with the Eagle County School District, to replicate the Valley Settlement process in their own communities.”

Inspired by the changes he saw in his wife, Ricardo quit his two jobs and took a pay cut to work as a paraprofessional at Crystal River Elementary School. He also volunteers as a Parent Mentor under his wife’s supervision. “I saw the change in Alejandra, so I changed my schedule so I could become part of the Parent Mentor program. Now that I’m working with kids, I’m learning, and I think I’m becoming a better dad.”

He puts his phone away and smiles at his wife, holding their young daughter on his lap. “You have to change your mind to ‘I’m going to.’ And now look.” He pats his wife on the knee. “Now she’s my boss.”