Change Agent

After the remodel, Victor Lundy’s iconic brick fireplace wall will remain.

Image: Derek Skalko

Aspen from 1945 to 1975 attracted many architectural talents who had a significant impact on the built landscape.

The Aspen West End home Victor Lundy designed in the early 1970s as a studio for his wife and a vacation place for his family presents itself rather formidably on two sides. Facing a Herbert Bayer–designed house on one side and Lake Avenue on another, its nearly twenty-foot-high iconic walls are mostly uninterrupted brick.

In fact, three of the walls are all brick, inside and out. The fourth, facing Triangle Park, is a two-story black-mullioned glass pop-out engineered with the advice of Hannskarl Bandel, who helped Eero Saarinen build St. Louis’s Gateway Arch. On this side, doors open to the garden.

Image: Derek Skalko

Inside, the bricks rise almost to the ceiling, indented near the wall’s base by a long horizontal wood-burning fireplace, below which a brick ledge bench runs the width of the wall. During the day, the bricks are washed by sunlight pouring through long clerestory windows, and at night by the moon.

The opposite side of the interior is also brick, bisected only by a marble counter running that wall’s width, with fir cabinets and appliances below and a single fir shelf above. Behind that wall, in a glass pop-out attached to the exterior brick, are two stacked bedrooms—one at ground level and one above—that face Aspen Mountain.

The feel of the interior is one of profound serenity, simultaneously open and private, the main volume screened with almost fortress-like solidity on three sides, and on the fourth open to the landscape.

Lundy thought of this house, he said in Sculptor of Space, a documentary video of his work, as a garden house, a place where he, his wife, Anstis, a painter who loved Aspen and taught at the Anderson Ranch Arts Center, and their sons contemplated the mountains and the sky for forty years.

Image: Derek Skalko

The home’s fluency of form, flow, and function reflect Lundy’s training at both NYU, where he studied art and architecture in the Beaux Arts tradition before enlisting in the Army during World War II, and Harvard, where he studied with minimalist master Walter Gropius and earned his undergraduate and graduate degrees. Lundy’s work includes churches; motels; the Atoms for Peace Pavilion, a biomorphic inflatable pair of connected domes that housed a traveling exhibit for the Atomic Energy Commission; and the U.S. Embassy in Sri Lanka, a commission that took twenty-three years to be realized. Lundy’s U.S. Tax Court building in Washington, D.C., now federally landmarked for preservation, is a structure that Ada Louise Huxtable, then the New York Times architecture critic, characterized as an expression of the heart, hand, and mind working together, a testament to simplicity and elegance in design.

Lundy’s Aspen house is a personal modern masterpiece, recognized as architecturally and historically significant, and yet, after Anstis Lundy died in 2009 and the Lundy sons a few years later decided to sell, “the property had absolutely no protection from demolition,” says Aspen’s Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) officer Amy Simon.

Lundy’s Aspen house is a personal modern masterpiece, recognized as architecturally and historically significant.

Image: Derek Skalko

“Aspen had changed around this house,” says Derek Skalko, an Aspen-area architectural designer who was hired to help the HPC evaluate Aspen’s midcentury buildings and whose deep commitment to preserving exceptional historic properties is evident in both his built and in-progress work.

The south-facing bedrooms with floor-to-ceiling glass walls that in the early 1970s framed less obstructed views of Aspen Mountain and Shadow Mountain now face the back of the duplex across the alley. The mountains are still visible above, but less of them, since the duplex is closer to the alley property line than the house it replaced.

The West End remains Aspen’s cultural heart and soul, still dominated by nineteenth-century Victorians, albeit many with additions that have doubled or even tripled their original size, and still anchored by the Aspen Center for Physics, the Aspen Institute, and the Benedict Music Tent. But rising real estate prices have brought redevelopment pressure, as have expectations of the size and amenities that should come with a multimillion-dollar residence. In 2011, when the Given Institute, a 1972 building seen as another embodiment of Aspen’s intellectual ideals, was torn down, the need to move quickly to preserve Aspen’s midcentury architecture became apparent.

Aspen from 1945 to 1975 attracted many architectural talents who had a significant impact on the built landscape. Fritz Benedict, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, arrived in 1945; Bauhaus powerhouse Herbert Bayer, already famous for his typography, graphic design, and photography, was invited by the Paepckes in 1946; and many others—Gordon Chadwick, Charles Gordon Lee, Sam Caudill, Charles Paterson, Ellie Brickham, Jack Walls, Ted Mularz, and Tom Benton—soon followed. They designed buildings that expressed modernist values: integrating interior and exterior landscapes, favoring the flow of space over rooms, and preferring volume over mass, with “unmodulated” wall surfaces and flat roofs, according to Margaret Supplee Smith, quoting Spiro Kostof’s A History of Architecture in her 2010 paper “Aspen’s 20th Century Architecture, Modernism 1945–1975,” which the Aspen planning office had commissioned to document the city’s architectural history and provide an informed basis for identifying historically significant properties.

Image: Derek Skalko

Benedict designed the first Sundeck on Aspen Mountain, the original Pitkin County Library on Main Street, and the since-demolished base lodge at Aspen Highlands, and he conceptualized much of Snowmass. Bayer was heavily involved in the design of the Aspen Institute and the restoration of many classic Victorians in town, including the Wheeler Opera House and the Hotel Jerome. Bauhaus founder Gropius advised on town planning in 1945. Elizabeth Paepcke commissioned Eero Saarinen to design the Music Tent in 1949, Buckminster Fuller to design a geodesic dome in 1952, and Harry Weese to design the Given Institute in 1972.

Preserving Aspen’s midcentury architecture had been identified as a priority in the early 1980s, but AspenModern, as the midcentury preservation program later became known, gained attention in 2000, when Simon put together a list of midcentury properties to be preserved. Many of the owners of the listed properties were appalled.

“People went bonkers,” says Bill Stirling, a forty-three-year resident of Aspen who served as mayor from 1983 to 1991. In 2007, Mick Ireland, then Aspen’s mayor, appointed Stirling chairman of a twenty-two-person task force charged with exploring whether and how post–World War II architecture could and should be designated as landmarked in Aspen. Though Stirling, who lived in a landmarked Victorian at the time, saw Aspen’s midcentury architectural heritage as important, not all midcentury-property owners agreed. Some challenged the HPC’s view of the architectural merits of their property. Others accused the city of taking value by limiting development potential. The debate quickly became emotional.

In October 2009, the task force delivered its recommendations to Aspen’s city council. As with the existing program for Victorians, the AspenModern criteria for landmark evaluation included the relationship of the property to significant people, events, or trends; its embodiment of characteristics particular to a type or period or method of construction; the property’s significance to the city; and the integrity of its location—all of which would be documented in a “context paper” written by outside consultants.

Because support for preserving midcentury buildings was less universal than for Victorians, the task force recommended that AspenModern landmark designation be entirely voluntary and that the city offer incentives, including an expedited review process, fee waivers, and tax relief, to homeowners willing to landmark their property.

Image: Derek Skalko

The calculus of incentives and trade-offs can seem complicated—and in application is something of a Chinese puzzle—but it was designed to make saving a historic property more appealing than razing it.

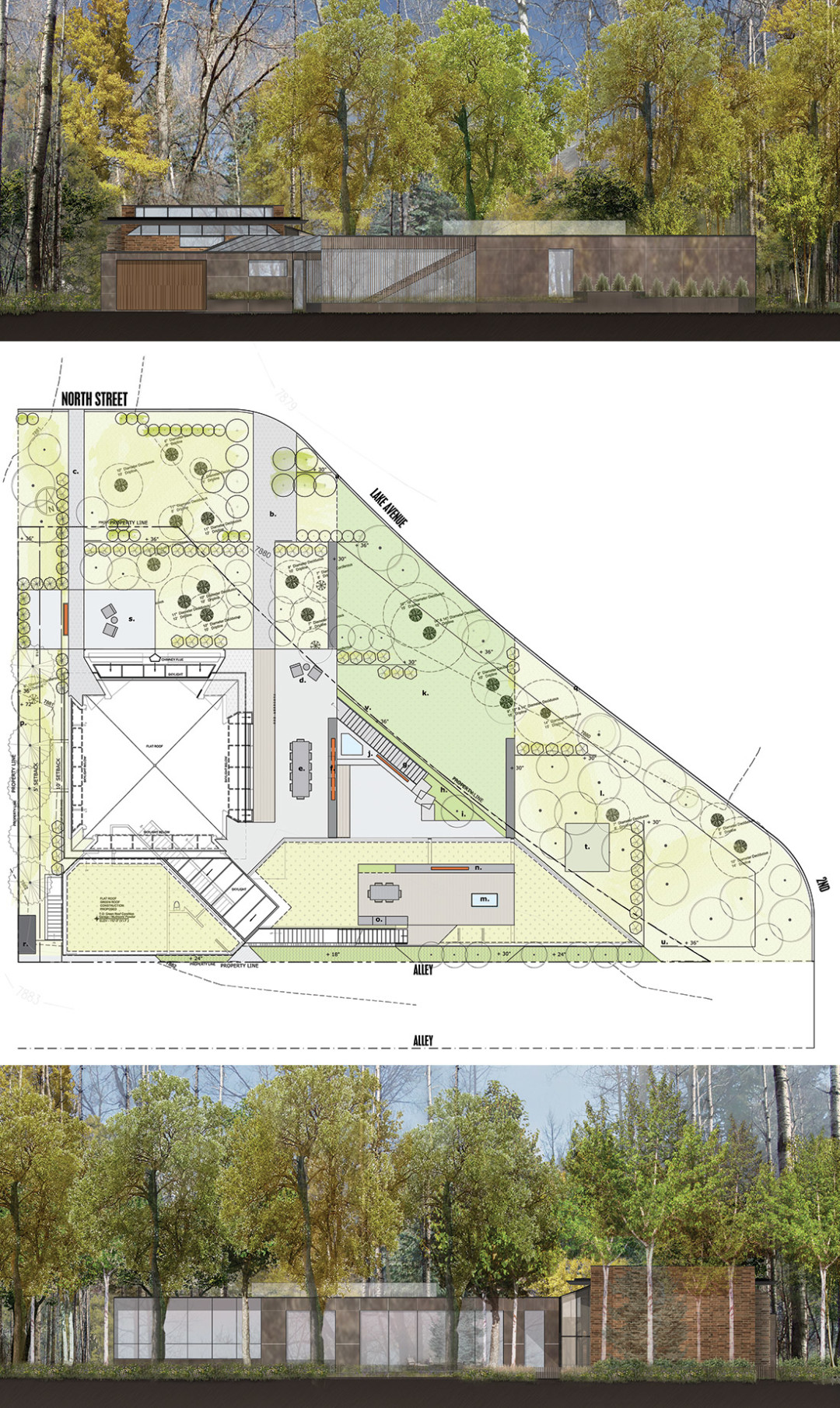

And so it was for the Lundy House: the Lundy sons on their own offered a cash incentive for the buyers to landmark the house within a year. The buyers, David Willens and Bill Boehringer, hired Skalko and his 1 Friday Design to come up with plans that would address what they perceived to be current market needs while preserving the iconic property. In exchange for incentives that included an expedited review process, waived fees, increased square footage, and a lengthened vesting time for development rights, Willens and Boehringer agreed to landmark the house in perpetuity.

While preservation purists, and perhaps Lundy himself, might prefer that no visible alterations be made, Skalko’s design is a mix of pragmatism and idealism that meets the criteria of the AspenModern designation and provides the kind of living space and energy efficiency that people buying houses in Aspen’s West End now seem to expect.

The challenge, Skalko says, was and is: “How do we ensure its viability for the next forty years?” Skalko, whose clean, light-filled reworkings of other historic properties respond to the scale, mass, and aesthetics of often much smaller originals, says he likes to think his design honors the architect and his family, the community, and the neighborhood, and preserves and complements the Lundy-designed original.

“What’s great about the house will remain,” he says.

His plans include retaining the Lake Avenue brick wall with the fireplace and the bench, as well as the glass wall facing the courtyard and Triangle Park and most of the great room. The kitchen will move to the wall on the Bayer house side.

The addition, as shown in Skalko’s renderings, will be a rectangular volume that runs the lot’s length along the alley. Above ground, it will contain a dining area, a secondary living area, a master bedroom and bathroom, stairs to the lower level, and a two-car garage. Below grade, lit by skylights and a so-called courtwell—an excavated courtyard designed to let natural light into the lower level—Skalko has drawn three bedrooms, another living area, a fitness room, and a wine storage area.

Image: Derek Skalko

The addition will more than double the house’s current square footage, but HPC’s Simon views the Lundy project as “an excellent example of our voluntary program working. The city’s commitment to offering incentives for designation is a win for the community and property owner. The addition is lower in height than the original building and off to the side. It’s clearly secondary to the original.”

Much of the rectangular volume will be sheathed in cold rolled steel, harmonious in color and surface with the original. The roof will be flat, planted with native grasses, and include a deck. The intent is to meet the new owners’ expectations and upgrade energy efficiency in a structure that makes an architectural statement for its time and complements the original.

And as Skalko puts it, the deeper objective is to “strike a successful balance between what Aspen was and what Aspen is.”