Inside a Miami Starchitect's Disappearing Act on Red Mountain

Rustic materials pair with elevated ceilings to impart warmth in a distinctly modern home.

Chad Oppenheim has a publicist in New York, an assistant in Miami, and a schedule so tight that his people will e-mail you to let you know he has ten minutes five minutes from now—more like a celebrity than an architect.

When it comes to architecture, Chad Oppenheim is indeed a bit of a rock star. His firm, Oppenheim Architecture + Design was named AIA Miami Firm of the Year in 2013, and Oppenheim himself has won more than sixty career distinctions since opening his Miami-based firm in 1999. His portfolio spans twenty-five countries and ranges from fanciful resorts in exotic locales to modernist residences for clients so high-profile that their locations are marked “confidential.”

Pocket doors enclose a cozy bunk nook fitted with two king-size mattresses.

So when the time finally comes for that long-awaited phone call with Oppenheim, it’s surprising to discover someone who is both accessible and somehow familiar, like a distant cousin or an old friend from high school. His story is familiar, too: he’s just a kid from Jersey who fell in love with Aspen on a ski trip with his parents when he was fifteen. Mesmerized by the sparkling lights of the homes on Red Mountain, he promised himself he would one day own a home here.

It’s also surprising that when it finally came time to build his Aspen dream home, Oppenheim would choose to renovate a thirty-year-old ski chalet on Red Mountain rather than start from scratch. And perhaps most surprising of all: the 3,500-square-foot renovation is tiny by Aspen standards.

Oppenheim calls the view from this nook of the master bedroom “like a painting.” BELOW: The existing home’s imperfections became a chance to play with space and light.

“The house is one of the smallest on Red Mountain. It literally could fit within the living room of the house below us,” Oppenheim says. “But we wanted that intimate, cozy cabin experience.”

What attracted him to the property was the mountain landscape, so his goal from the start was “to make the house disappear,” he says, by stripping everything down to the skeleton and rebuilding to integrate the house into the natural setting.

“We wanted nature to be the star and to work with the idea of a house having its own soul and energy.”

Oppenheim chose natural materials like local stone, regional wood, and weathered steel and copper to achieve seamlessness between the house and its natural surroundings. He even went so far as to hide electrical outlets, drains, light fixtures, and doors.

But the bones of the original structure themselves provided ample opportunity for interesting configurations of space and plenty of play with natural light. Pursuing the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi—the idea of beauty in the imperfect—the architect sought to utilize some of the ski cabin’s incongruities while respecting its original character.

“The house had this incredibly haphazard structural system with wood columns and beams throughout that are very expressive and crudely put together,” Oppenheim says, “so we really played with that.”

All of the floors are made from old wood, and many of the walls and ceilings have reclaimed wood paneling, lending a sense of warmth in much smaller spaces than you’d expect to find in a modern home. Take, for example, what Oppenheim describes as the “fantasy of a bunkroom,” a nook covered wall to wall with two king-size mattresses that are draped in shearling pillows and blankets and enclosed by pocket doors that disappear into the walls of the larger room on the other side.

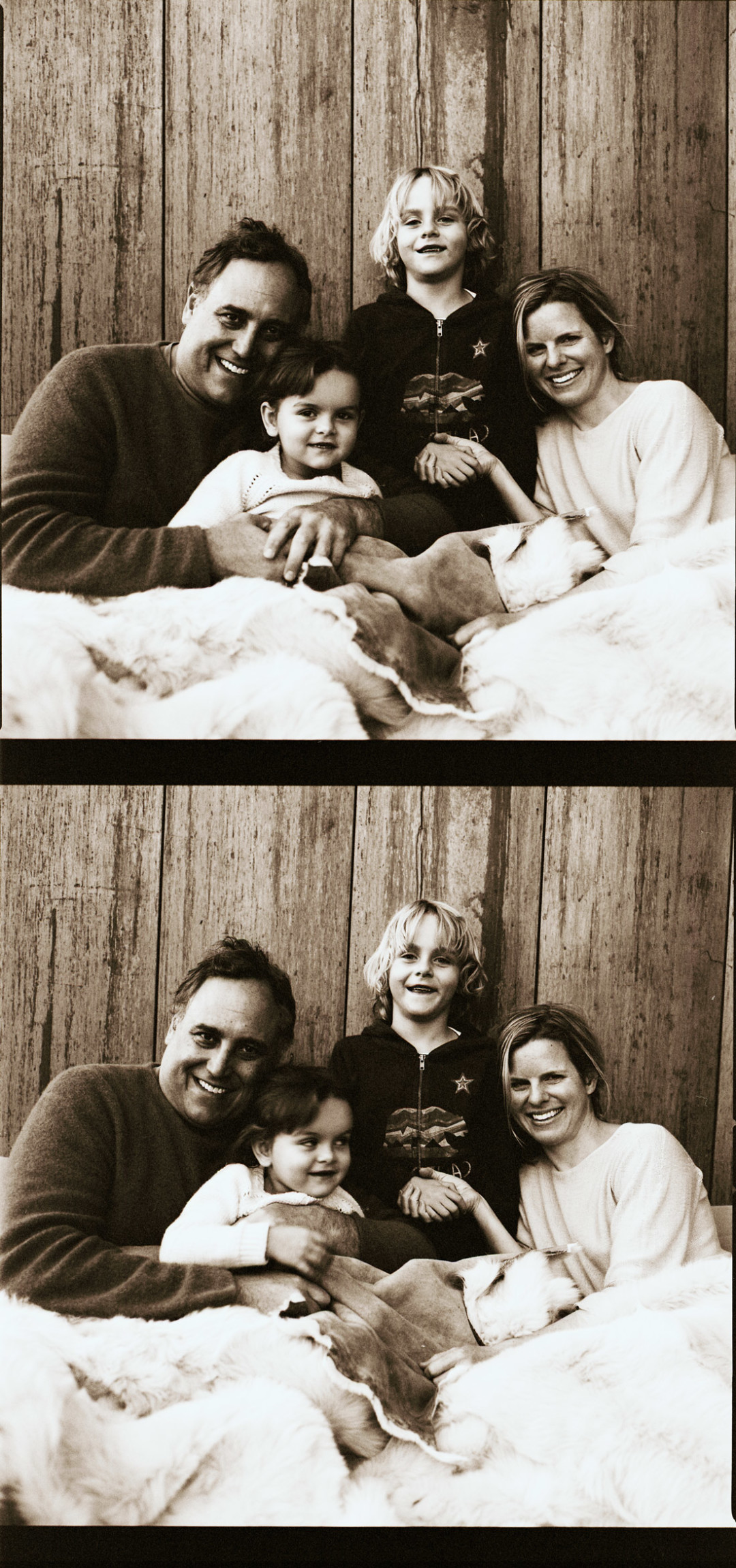

Chad Oppenheim and his family in their Red Mountain home

Image: Derek Skalko

The kitchen is also relatively small, made to feel even more so with its low ceiling. A built-in leather banquette and large center island function as the home’s central gathering place.

Juxtaposing the overall rustic feel are plenty of open spaces with elevated ceilings that have a distinctly modern flair. And each room focuses on the views, with windows strategically placed to optimize the dramatic prospects.

“It’s like this big glass box; there’s no contrast between the solidity of the wall versus the view,” Oppenheim says. “In the master bedroom there’s this huge window at the end of a narrow room. The impact of that is almost like a painting.”

Overall, Oppenheim’s restraint reflects a deep respect for place over design that is unexpected from a man who has achieved such astounding success in architecture. Yet his philosophy speaks to the heart of his business.

“Our goal was to get closer to living in the mountains at its purest expression: a home as a shelter and a place to commune,” he says. “A house isn’t something to be looked at in a magazine or to impress someone. It’s something to be experienced.”