Political Animal

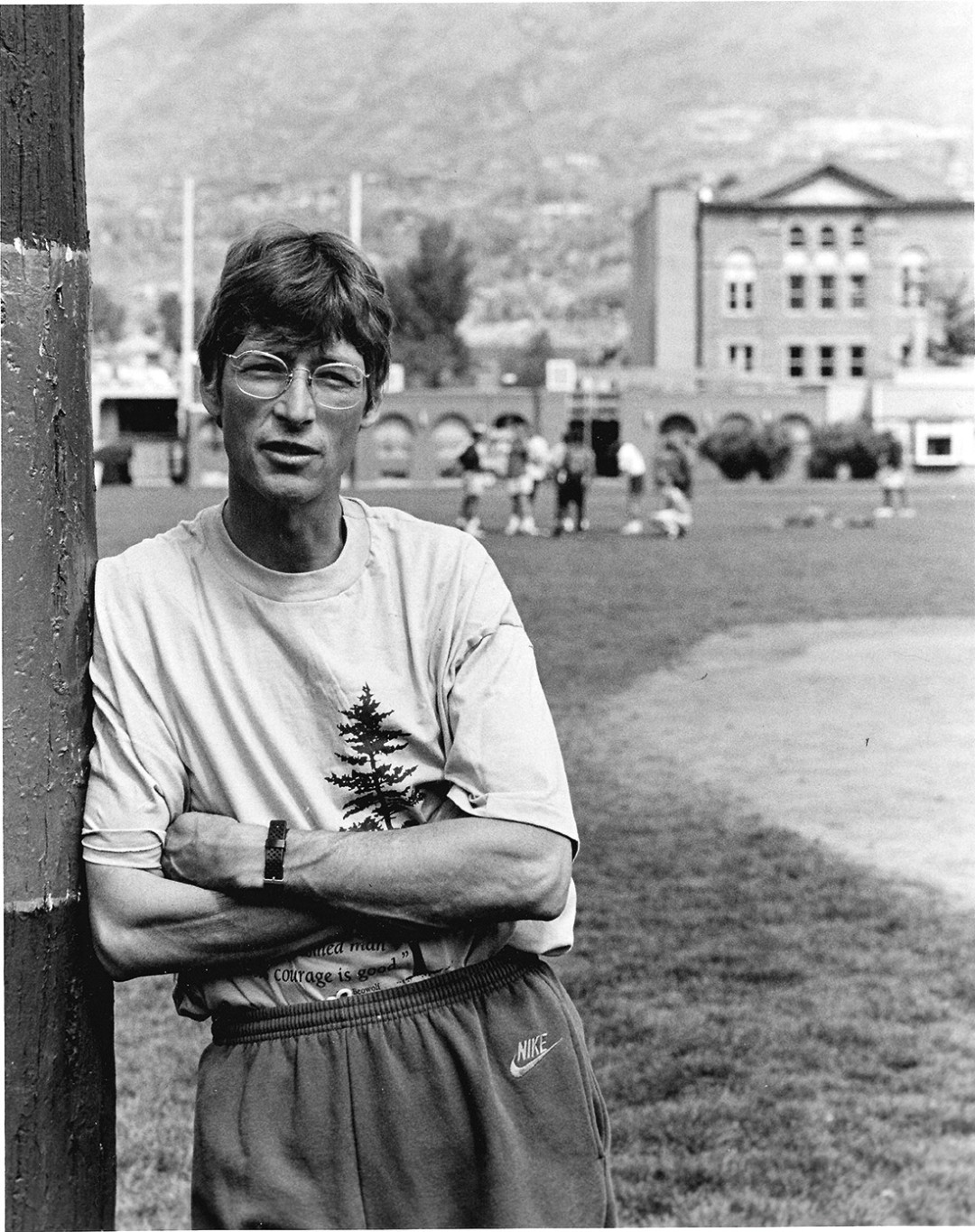

Mick Ireland is a lawyer (University of Colorado Law School, class of 1988), a diehard cyclist (he has biked from Aspen to meetings in Denver and Meeker), a clueless dresser (bicycle tights are standard attire for his daily rounds), a self-described “geeky intellectual,” and an uncle who takes the role seriously, exerting significant influence on a niece and nephew who were raised here.

Ireland is also Aspen’s most recognizable political brand. He concludes his third term—the maximum allowed—as mayor this spring, and he has been through ten local elections, all victories. At the same time, he is town’s most polarizing politician. Being anti-Mick has become practically a cottage industry. Two of his ballot appearances were in recall efforts against him; a recent campaign season was marked by “Sick of Mick” bumper stickers.

Ireland's politics have never been laissez-faire. His sartorial sensibilities always have.

Image: Courtesy: Aspen Times

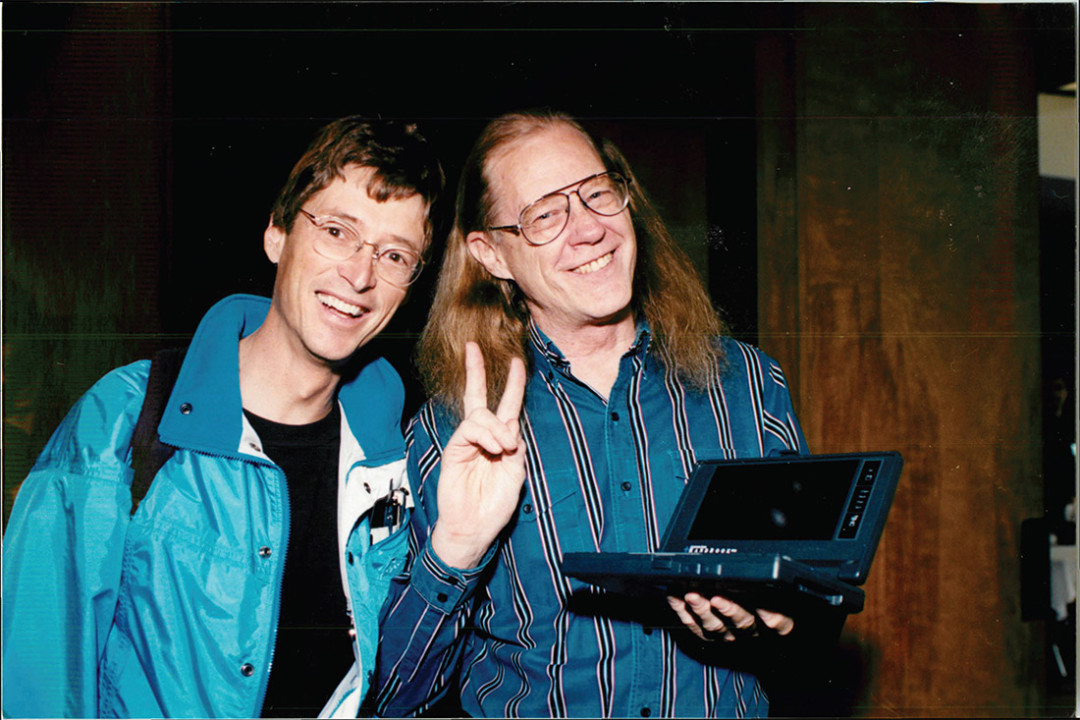

The role in which he excels most, though, might be as a numbers guy. Fellow politicians—both supporters and foes—marvel at Ireland’s grasp of campaign demographics, and he is occasionally hired to track voter databases, neighborhood by neighborhood, by others running for office. In 2006, when Snowmass Villager Gail Schwartz ran for Colorado Senate, a TV station called the race for her opponent. Ireland insisted otherwise—by his tally, which included districts that were late in turning in votes, Schwartz was going to win. The next morning, she had been elected, with 51 percent of the vote.

The number that has most motivated Ireland’s twenty-year political career is 200. That represents, by his count, the population of a 1.6-square-mile patch of the Vail Valley, along I-70, marked by the most popular ski mountains in the U.S., a mass of condos, and few actual residents. Over three terms as a Pitkin County commissioner and three as Aspen’s mayor, Ireland has made it his mission to steer Aspen clear of that fate. In doing so, he has carried on a populist local political legacy that dates back to the late ’60s: putting community preservation above a development-oriented expansion of the resort.

In the ’90s, as county commissioner, he fought for rural and remote zoning, which significantly limited development rights in backcountry and outlying areas. (That contentious battle led directly to the two recall efforts.) Ireland helped turn the local bus service into a regional transit agency, an effort that had him lobbying at the state level and eventually winning the support of a Republican-controlled legislature. On environmental principles, he pushed hard for building a hydroelectric plant on Castle Creek. Last year, voters rejected the proposal.

But surely the most bedrock piece of Ireland’s platform has been affordable housing—providing locals a chance to live in or near the town where they work. When he took office, the housing program included approximately 1,100 units. In the twenty years since, Aspen and Pitkin County combined have added approximately 1,700 more, either built, subsidized, or mandated by government.

“[Aspen’s] vitality is based on the fact that we’ve maintained artists, cops, journalists, ski patrollers in affordable housing. If not for affordable housing, we’d be just like Vail, which is basically empty,” says Ireland, who himself lives in a one-bedroom townhouse in the Common Ground affordable housing project. As proof, he points to Aspen’s West End neighborhood, which has virtually no subsidized worker housing. “The West End has gone dark—it’s lost population for three consecutive censuses. Without affordable housing we’d be done.”

Image: Courtesy: Aspen Times

The relentless advocacy for worker housing—and in Aspen “worker” is as likely to mean a master sommelier or a CPA as it is a ski lift operator—has crystallized a debate that has proved ongoing, between Ireland, in favor of an activist government, on one side, and free-marketeers on the other. Among the heated skirmishes in Ireland’s career was one in 2008 over the ballooning cost of Burlingame, a ninety-one-unit project (with a second phase in progress that will add 167 units) built by the city.

The housing concept has spread downvalley, and Ireland has often consulted with other resort towns, including Sun Valley, Asheville, NC, and Vail, that aim to emulate Aspen’s model. “We’ve changed the way we think about what a resort can and should do,” Ireland says. “And it’s working—people pay more to come here than to ski the same snow in other places. That’s not a marketing paradigm; that’s more because of the locals. We have something spiritually and culturally that you don’t find in other resorts.”

Helping Aspen maintain a diverse population, where ski bums and billionaires often do mingle, has meant sacrifices for Ireland: financial opportunities, social life. His detractors would add social skills to that list. “He’s rude. No question in my mind,” says Helen Klanderud, who was elected to three terms as mayor prior to Ireland. Klanderud’s would be among the milder critiques. Those on the receiving end of tongue-lashings at public meetings would say that Ireland’s reputation for being abrasive and dismissive has been well earned.

Image: Courtesy: Aspen Times

Ireland—sixty-three, never married, not a mover in Aspen’s upper social circles—considers the interpersonal friction to be the side effects of a greater purpose. “This is like a calling,” he says. “Like someone who climbs Mount Everest—because you can, because you have the skill and equipment. I can do this. I know politics. I can make this a better place. You’re the guy walking along the dike, and your thumb is big enough—you do it. It’s important.”

Ireland’s family owned Ireland’s Oyster House, Inc., a Chicago restaurant successful enough to provide a house in the affluent suburb of Mt. Prospect—“whiter than Aspen,” Ireland says—and private schooling, on occasion, for Mick and some of his seven siblings. But in the late ’60s, a relocation of the restaurant went disastrously bad and the family adjusted dramatically downward. Ireland, paying his own way through college, began as a psychology major at Marquette, a private university, but transferred to the University of Illinois, a state school. Unable to afford the typical four-year college route, he mixed college with work. It took eleven years before he graduated.

Image: Courtesy: Aspen Times

Ireland’s interest in politics, though, and his specific political leanings, had already taken shape years earlier. In 1956, his mother was transfixed by John F. Kennedy’s bid for vice president and devoutly followed the Democratic National Convention. Six-year-old Mick became infected.

“When Kennedy came back, in 1960”—to run for president—“I was totally clued in. My best friend would bring in Nixon material and argue with me about Kennedy missing a subcommittee meeting on Africa,” he says. Ireland related especially well to Kennedy’s outsider status: “A Catholic becoming president? I was in Catholic school, and Catholics were like Hispanics: ‘Too many children.’ ‘We’ll never hire you.’”

By the time Ireland came along, Ireland’s Oyster House was no longer the hip hangout for black jazz musicians it had been in the 1930s. Still, the time Ireland spent there, through the 1950s and into the ’70s, sharpened his outsider’s perspective. “Dad decided black people could come in, sit wherever they wanted. That was controversial. In my grandfather’s day they sat in back,” he says. “The staff had black guys, white guys from the South, who couldn’t read or write. I’d have to write down their orders.”

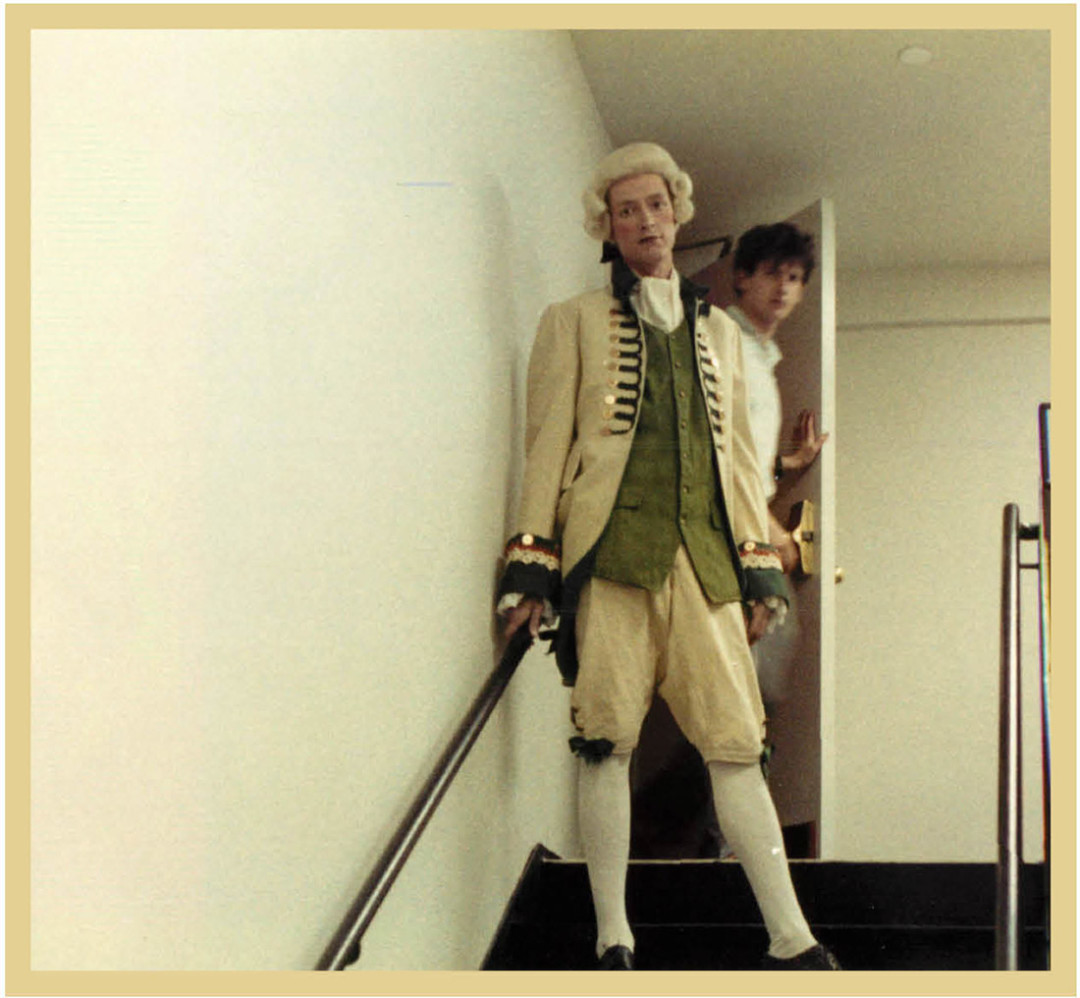

Ireland frequently dropped out of college to work—in the restaurant, in a lumber mill, at newspapers. Often the breaks were more about the adventure than the job. “Kerouac shit, you know,” he says. Ireland was a journalist in Alaska, where he made a contact who later fed him stories about the wild goings-on around the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. He worked for George McGovern’s 1972 presidential bid, hitchhiking across the country to pick up bumper stickers. Impressed, the campaign offered Ireland a plane ticket back to Chicago. He turned the ticket down, and thumbed home.

Image: Courtesy: Aspen Times

In 1968, the Marquette Avalanche Ski Club organized a trip to Aspen. Unable to afford the $15 bus fare, Ireland hitchhiked. He wasn’t much of a skier but loved the thrill of the mountains and the fact that he was willing to launch off catwalks that scared his friends away. He came back for the winter of 1970–71 to work at the Dormez-Vous, a $6-a-night lodge with four beds to a room.

On January 9, 1979, having finally graduated, Ireland headed to Colorado for good. After giving Keystone a brief trial, he came to Aspen and took a dishwasher job at the Mother Lode. He would also drive a bus and get involved in a grassroots effort to raise funds, through a local ballot measure, to qualify for a federal mass-transportation grant. The measure passed, and the transit agency received $6 million from Washington to build a bus barn. The campaign was opposed by what Ireland calls, “the Ayn Rand crowd, who said we shouldn’t do it.”

A year after moving to town, Ireland began covering the courts beat for the Aspen Times. “This was back when many of our prominent citizens had less orthodox ways of accumulating capital,” he says, referring to the drug dealers he wrote about. “There were serious concerns about my personal safety.”

Covering drug cases was a further test of Ireland’s willingness to take sides against powerful groups in Aspen. It also led him to believe the lawyers representing the dealers were no smarter than he was. In 1985, Ireland started law school at the University of Colorado Boulder, where he focused on tax law. His studies coincided with the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which changed the tax consequences regarding second homes. The effect in Aspen was immediate. Ireland says property values doubled over ninety days, and the social effects were as drastic as the economic ones.

“I saw what I had studied manifesting in front of my eyes,” he says. “In the early ’80s, people would rent rooms in the West End. Because of the tax changes, owners no longer needed to rent. The work force that lived here dropped noticeably.”

In 1988, while working as an associate at a law firm, Ireland wrote an opinion piece for the Aspen Times. “Tax and Build or Say Goodbye” stated the core of his progressive beliefs. It went against the rightward movements of the Reagan years, but Ireland argued that for Aspen to maintain itself as a community, government had to build much more affordable housing. Later, in office, he would help institute a tax to fund Pitkin County’s Department of Health and Human Services.

Image: Courtesy: Aspen Times

“That political strategy—‘I want you to vote for me, and I want to raise your taxes’—was not widely emulated,” says Ireland, who entered public office in 1993, when he was appointed to fill a vacancy on the Pitkin County board of commissioners. (He was then elected to serve three subsequent full four-year terms.) “But you can’t have community unless there are shared burdens. People have lost this notion of public investment, as if things like RFTA [the valley-wide bus system] and affordable housing would exist without the public sector.”

Pursuing his agenda with conviction has meant alienating a significant portion, or at least a vocal portion, of the public. Yet Ireland has been elected every time he has run for office. Should he extend his political career with a city council bid this spring—a prospect he is considering, and one that instantly activated the anti-Mick faction—he would likely be the front-runner.

“I think he represents the desire to control growth and protect the environment,” says Rachel Richards, a current Pitkin County commissioner and a former Aspen mayor and city councilperson whose political aims have been essentially aligned with Ireland’s. “Even people in development, they respect the idea that there’s a golden goose that could be killed if there are real changes in the character and scale of Aspen. Mick always represents a backstop to that and the idea that restaurant workers, journalists, and ski patrollers are as important to the community as a second-home owner.”

But Aspenites have also been partial to Helen Klanderud, whose own three terms as mayor were marked by a more business-friendly approach. While she commends Ireland’s commitment to affordable housing and expresses awe at his campaigning skills, she believes Ireland’s vision rejects even a healthy rate of growth.

“There’s a lot of ‘no’ going on—‘no’ this, ‘no’ that—and I’m not sure that’s good for the community,” says the more socially outgoing and popular Klanderud. “I don’t think you can put the lid on so tight. If you don’t grow at all, that’s stunted.” Klanderud points to the proposal to develop the base of Aspen Mountain near Lift 1A, a generally overlooked neighborhood, with a big hotel and other attractions. That proposal has been stalled before city council for years, and Klanderud faults the government for not being more receptive. “Clearly, lodging should go at the base of the mountain. That’s a true missed opportunity for this community.”

Image: Courtesy: Aspen Times

But in Aspen, where the financial stakes are extreme and vast resources are thrown behind development proposals, voters have viewed someone like Ireland—the guy who is willing to say “no” and take the consequences—as a necessity. Ireland believes it is this mayor-as-roadblock dynamic that feeds the perception of his being abrupt. For a wealthy landowner seeking permission to build a dream mansion, simply having the application denied can seem like rudeness.

“They’re not used to being told, ‘No.’ And they’re not used to hearing it from a mere country lawyer, a dishwasher,” Ireland says. “I’ve had people stand up in a meeting and say, ‘My maid doesn’t expect to live in the same city I do. Why should you expect your maid to live in the city you do?’ Well, I was the maid.”

Despite the disconnect between the glitz of Aspen and the shabbiness of its mayor, Ireland believes he represents something close to the heart of town. “I’m not at all glamorous,” he says. “But people are surprised that the town itself is not as glamorous as the media would have it. They come in to write about the number of jets, the Charlie Sheen trial. But you get here and see so much more of a real-town flavor.”

Ireland is unglamorous by inclination. He would rather bike or ski or work than dress up for a benefit. Neither a glad-hander nor an arts lover, he is seldom seen at the sort of functions one might expect a mayor to attend. When he does appear at such events, he doesn’t necessarily behave as expected. Last summer, at the opening convocation for the Aspen Music Festival and School, he had several hundred out-of-town youngsters laughing—and stunned—as he warned them not to smoke pot in the woods, because of fire danger. Nobody would care, Ireland told them, if their marijuana was medical and legal.

But Ireland also believes that the way he has led his political life—pursuing firm, sometimes controversial convictions with passion—has made him socially “radioactive” and excluded from the glitzy sides of Aspen. “People don’t want you at social functions where a certain percentage of the attendees are angry at you, against you. I’ve had people say, ‘I can’t be involved with you because of the political baggage.’”

Consequently, much of his life has a real-town flavor to it, or at least Aspen’s version of real-town existence. Among his favorite ways of advocating for the town is to meet tourists on a chairlift, then give them a local’s view of the ski mountains. “That’s an important part of their experience. They might be a CEO, but they get the vicarious fantasy of their life revolving around how much powder we get,” he says.

Away from politics and recreation, much of Ireland’s life revolves around family. At one point he had three siblings living in the area. His sister Molly, a thirty-year Aspen resident who has worked at the Pitkin County Library for two decades, is still here and functions as something of an anchor for her brother. She notes that her two children, now young adults, were often given ethical guidance by Ireland, an input she welcomed.

Mostly, though, Ireland has sacrificed his private life, allowing the political life to consume him. He says his prominence as a politician has been the result not of his grasp of demographics, not of cozying up to the right segments of society, and certainly not of a warm and proper personality, but of making himself and his views widely known. More than anything, Ireland is an old-school politician who has put in the time knocking on doors, passing out fliers, and speaking—loudly, single-mindedly at times, with conviction always—about the issues he believes matter to the Aspen community.

“I’ve probably talked to more people face to face in campaigns than anyone who’s run here,” he says. “There are more popular people—Bob Braudis,” who was Pitkin County sheriff for twenty-four years. “But I talked to people about myself, school tax, open space tax. Odds are better than even, if you’ve lived here, you’ve seen me at your door.”