Sojourner Salutes

Image: Karl Wolfgang

With this Sojourner Salutes, an annual Aspen Sojourner tradition turns twenty. The first Sojourner Salutees were Kate McBride, Les Anderson, and Mary Ann Hyde—a skier/philanthropist, a former chair of the Music Associates of Aspen (MAA, now the Aspen Music Festival and School), and an MAA and Aspen Art Museum board member, respectively. Profiles of that group appeared in the winter 1995 edition of Sojourner (no “Aspen”), which was then a biannual hardcover coffee-table book distributed in hotel rooms. Since then, a total of seventy-two locals have been saluted (fifteen couples were honored with single Salutes profiles) for their positive impacts on Aspen and the Roaring Fork Valley. They include pro-tennis-player–turned–nun Andrea Jaeger (1998); members of a multigenerational Aspen family, David and Sigrid Stapleton (2000); and former Pitkin County sheriff Bob Braudis (2007).

The tie that binds them all? A demonstrable commitment to keeping Aspen special.

Image: Karl Wolfgang

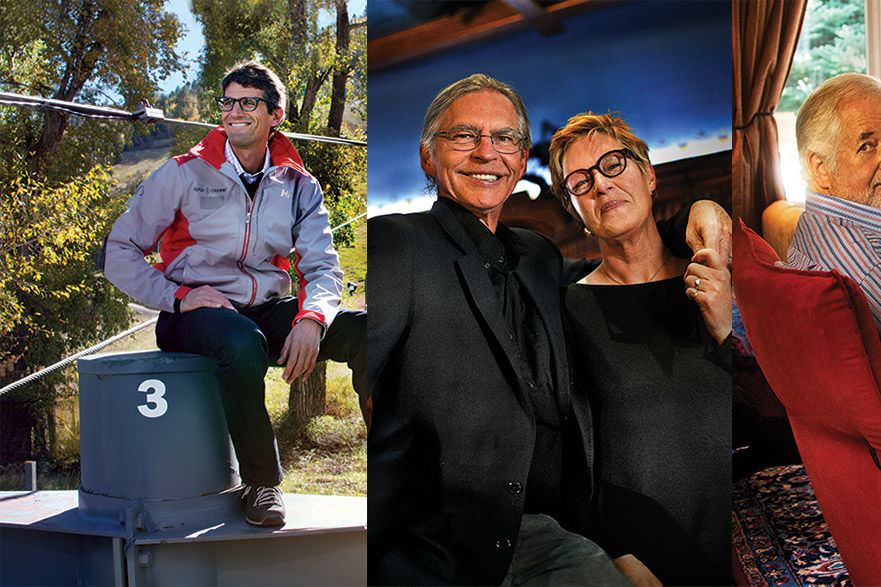

Laura Thielen and George Eldred

Directors of Aspen Film, curators of shared experiences.

When the credits rolled during the final presentation at Aspen Filmfest a few years ago, Laura Thielen and George Eldred could feel something special was happening. The collective euphoria was electric.

“You know when it hits a nerve,” says Thielen, who is co-director with Eldred of Aspen Film, Filmfest’s presenting organization. She recalls the movie that night at the Wheeler Opera House was The King’s Speech, which months later would win an Oscar for Best Picture. “There’s something wonderful,” she says, “about a group of people being simultaneously moved.”

Thielen and Eldred have been curating extraordinary experiences for Aspen audiences for the past twenty years. Having presented upwards of 2,500 films, the married couple opens a window for film fans to traverse a vast array of emotional and cultural landscapes—from a New Delhi colony of magician-puppeteers fighting to keep hold of their home to an Italian politician who runs away to Paris in search of himself to the travails and triumphs of the Lost Boys of Sudan to an eighteenth-century German love story in which two sisters share the same man. And that was all in a single festival (2014).

Founded in 1979 as Aspen Film Fest, the organization has continually expanded, particularly under Thielen and Eldred’s leadership. Today, Aspen Film presents four major programs annually: the flagship Aspen Filmfest in fall, Academy Screenings in winter, Aspen Shortsfest in spring, and the New Views documentary series (in collaboration with the Aspen Institute) in summer.

When asked what the two are most proud of in their tenure, Thielen doesn’t hesitate: “Our greatest contribution is in the fostering and nurturing of emerging voices through Shortsfest.” She is hardly alone in that assessment. Indiewire voted Aspen Shortsfest one of the top fifty film festivals in the world, alongside Cannes, Sundance, and Toronto. Acceptance into Shortsfest’s Oscar-qualifying International Competition is intensely coveted among filmmakers from across the globe.

Thielen and Eldred moved to the Roaring Fork Valley with their daughter, Caelina, in 1995 from the Bay Area, where he worked in film production and she for the San Francisco International Film Festival. They were among the first of Aspen’s arts and culture leaders to take programming downvalley. They began screening movies at Carbondale’s Crystal Theatre in 1996 and have been doing so ever since. They also identified early on the need for valley-wide youth education programming. Four months after joining Aspen Film, they launched Film Educates, an outreach initiative estimated to have reached more than 30,000 kids. Eldred says bringing students to the theater and filmmakers to the classroom is a key element of the organization’s mission. These exchanges, he notes, can have as profound an impact on the filmmakers as on the kids.

The couple’s work (which Thielen is quick to point out would be impossible without a battalion of staff, board, and volunteers) may be more important today than ever before. Ours is an increasingly insular society consuming media on demand and on personal devices. As such, the opportunity to come together in a community celebration of light and shadows on a screen that miraculously illuminates lives different from our own can attain the elevated status of the sacred.

—Julie Comins Pickrell

Image: Karl Wolfgang

Mike Kaplan

Aspen Skiing Company CEO.

But first, and always, a skier.

Mike Kaplan’s first skiing experience occurred in utero in 1964 at Taos, where his mom took lessons from an actual drill sergeant. Taos was still a nascent ski area in those days. Its founder, Ernie Blake, was a Swiss-German Jew who immigrated to the U.S. in 1938, interrogated Nazis for Patton during World War II, and founded Taos, the ski area, in 1954.

“He had a lot of intellectual curiosity,” Kaplan notes of his late mentor. Blake was known for reading on the chairlift. He named ski runs after Norse goddesses and war heroes. Though Kaplan remembers crying the first time his mother dropped him off at ski school, the skiing part clicked right away. Soon enough, his family developed a passion for the mountain, the culture, and the Taos Pueblo, and returned year after year.

In high school Kaplan raced, first at Wilmot, a tiny Wisconsin hill not far from his Illinois hometown, then at Stratton Mountain in Vermont, and later at the University of Colorado, where he studied international affairs. Jean Mayer, who still runs the St. Bernard, the legendary lodge he built at the bottom of Taos’s first chairlift, and who is technical director of the ski school, had become a close friend and ski coach. Mayer had skied for the French national team, directed the Garmisch ski patrol, and trained 10th Mountain Division soldiers. When Kaplan finished his B.A., in December 1986, he went to Taos to teach skiing with Mayer.

After the season, Kaplan spent seven months traveling in Asia, but he returned to Taos the following winter. There he met Laura, now his wife, and that spring he confessed to Blake that he, too, wanted one day to own and operate his own ski area. Blake told him that snowmaking operations would begin in October and to show up then if he was serious. Kaplan did, and for the next four years he worked his way around the mountain. He left for an MBA at the University of Denver, where he wrote a strategic plan for Taos, skiing sixty days at the mountain while researching.

That case study and others provided a framework for reflecting on the ski industry’s future, as well as on his own. Kaplan wanted to stay close to skiing; the only question was where. Aspen, he says, had “soul,” and in 1993 a Taos friend running Aspen’s ski school hired him to help. From ski school, Kaplan moved to mountain operations, then became chief operating officer in 2005. A year later, when Pat O’Donnell stepped down, Kaplan was named CEO.

Kaplan saw his role as evolving O’Donnell’s emphasis on climate change, customer service, and values-based management. He lobbied in Washington for climate change awareness and serves on the board of the Aspen Community Foundation. In saying yes to lift tickets that are tiny works of art and to installations on the mountains, he helped actualize the SkiCo’s relationship with the Aspen Art Museum. The Aspen Skiing Company has become a regular on Outside magazine’s list of the 100 Best Places to Work.

Of what is Kaplan proudest? His four kids, of course. Also, that he did the Power of Four last year with fellow SkiCo exec Rich Burkley.

Kaplan skis about 100 days a year, for at least one run. He’s always looking for lines he’s never done. “It’s about being out there,” he says. “It could be about the icicles hanging off a tree one day, or the light off the clouds.”

—Susan Benner

Image: Karl Wolfgang

Loren Jenkins

Pulitzer Prize winner serving globally as well as locally

Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Loren Jenkins never planned on becoming a war correspondent. That he became a journalist at all can be blamed on Aspen. With his mother and father in the American Foreign Service, Jenkins lived all over the world. Friends of his parents had moved to Aspen to run the Copper Kettle restaurant, and Jenkins came to work for them in 1955, when he was seventeen.

“I never had a permanent home in the U.S., so when I got here and looked around I decided this was it,” he smiles. “I bussed tables, boot-packed for lift tickets, and eventually taught skiing for Fred [Iselin] and Friedl [Pfeifer]. It was great.”

After graduating from the University of Colorado and stints with the Peace Corps in Puerto Rico and Sierra Leone, he returned in 1964 to Aspen, where he would often climb with David Michaels and Bob Craig. The latter involved him in the Aspen Institute. “That got me thinking much broader than just being a ski bum and was very influential in setting me on another path,” he says.

That same year, Jenkins met Hunter Thompson before leaving for graduate school at Columbia and becoming involved in the civil rights movement. “I was interested in foreign affairs,” he says, “but I didn’t want to work for the government like my parents. By a process of elimination I decided on journalism.” He contacted Thompson, the only journalist he knew, about breaking into the business. “He wrote me a gonzo letter of advice,” he says, “but warned it was a nasty profession.” They remained lifelong friends.

Starting small in Westchester, New York, Jenkins ascended to United Press International in New York City, London, Madrid, and Paris. After leaving UPI for Newsweek, he returned to Madrid before postings in Beirut for Black September and the Suez war, then Saigon in 1972, serving as the magazine’s last bureau chief there. Beginning in 1975, he worked from Rome for fourteen years, including covering the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon for the Washington Post, for which he received the Pulitzer.

All of that combat didn’t prepare him for becoming editor and part-owner in 1991 of the Aspen Times. “During his tenure,” wrote Times reporter John Colson, “both the quality of the news writing and the look of the paper were improved and modernized.” But, “over time I fell out with my partners over editorial policy,” explains Jenkins. Soon after his resignation in 1995, he was named as editor of the international desk at National Public Radio, where he worked until moving back to Aspen to write in 2013.

—Jay Cowan