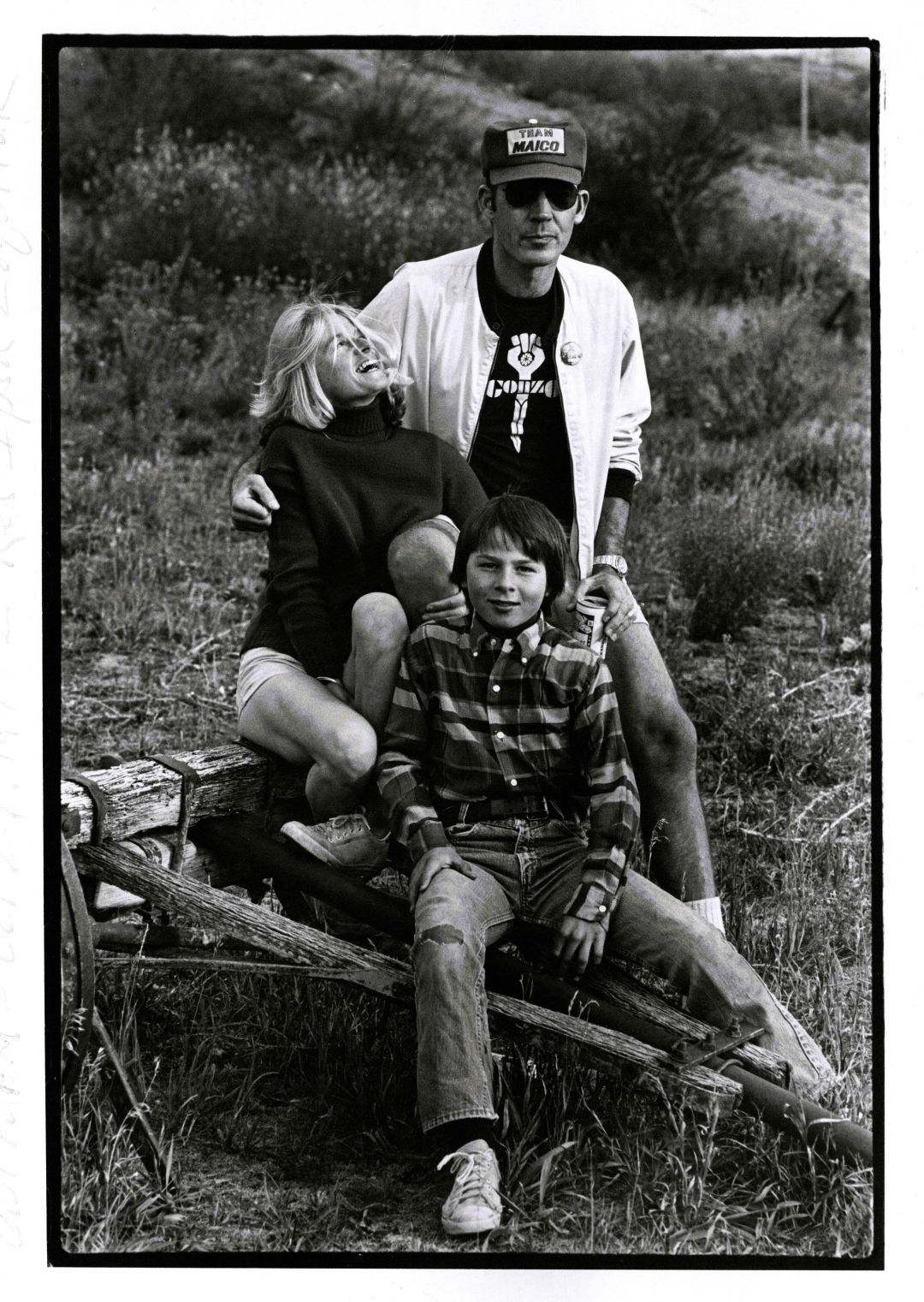

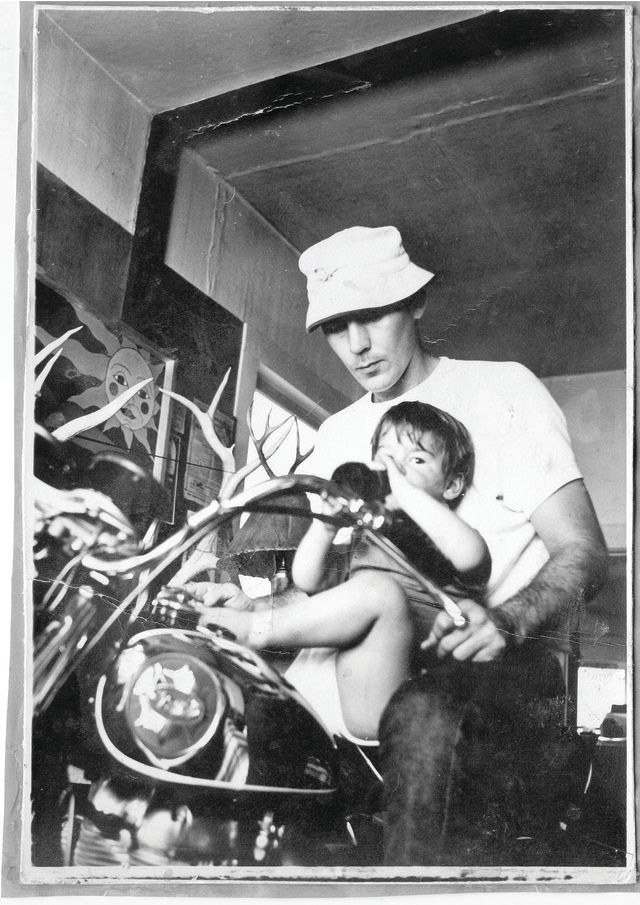

Growing Up Thompson

Image: Ralph Steadman

The just-published Stories I Tell Myself is the highly subjective memoir of how my father, Hunter S. Thompson, and I, his only son, got to know each other during 41 years, until his suicide in 2005. It’s the story of how my father and I went very far away from each other, and how, over the course of 25 years, we managed to find our way back before it was too late. The following excerpt is from Chapter 6. Just before I left for my freshman year of college in Boston in the fall of 1982, Hunter and I had spent a week together at Owl Farm in Woody Creek. This was my state of mind afterward.

Image: Bud Lee

As I was getting on the plane in Aspen to fly to Boston, Hunter gave me a letter. He told me to read it once I was in-flight.

Sept 1 ’82

Dear Juan

Okay. You’re off. And things seem generally under control—on your end, anyway. I am still juggling madness on this end, + I’ve never even heard a rumor that the end might be in sight.

It’s a queer life for sure—but at least it keeps me in shape, more or less.

Here are three valid $50 checks, which should keep you solvent at least long enough to settle in + get a fix on things. Use them to open your own bank account in Boston.

Also, call me tonight to confirm your safe arrival. Don’t forget to do

this. Tonight.

The sheepskin jacket is a present from Laila. Boston is cold in the winter.

I’ll call Dick + Doris [Goodwin] + Mike Barnicle at the Globe, to say you’ll be stopping by sometime soon, to say hello, etc...

And so much for advice + logistics. I’m not worried about you—but I am interested, and I’ll want to know what’s happening. Send me your phone number and a P.O. address. Let’s talk on the phone as often as you feel like it—especially for the first few weeks, which will almost certainly be nervous. Or maybe not. But if they are, don’t worry. The Glum Reaper will be hanging around, but to hell with him. We have dealt with the bugger before + we know the one thing he can’t handle is a bedrock sense of humor.

So remember the 44 “Naked + Alone . . .” books. All you have to do is write the first two. I’ll handle it after that, + we will both get obscenely rich. Take my word for it. Why fool around with tangents, like all the others? Your future is already assured. All you need is a typewriter + a few reams of paper.

I’m glad you came home for a while, + I wish it could have been longer. I had a good time—and as always, was proud of you. Very few seekers go out in the world as well-armed as you are.

I’ll keep after [Paul] Rubin for the $1000 he owes you for technical work. He says he has a fat job for you next summer—but so do I, and mine is a lot fatter. 44 books, rich + famous by 21. No problem...

Anyway, I’ll figure on seeing you for Xmas, if not before that. We had a wonderful time with Davison + his family last year, + hopefully we can do it again—either here or in Florida, depending on my Silk Road schedule. . . . So let’s keep this in mind + plan for it.

We still have a ways to go before we can act like good friends + yell at each other without worrying about what it all means. . . . But we’re doing pretty well, considering the small amount of time we’ve really put into it.

You’re a good person, and I love you for that as much as because you’re my son.

Or because you’re about to be rich + pay my expenses forever. With my wisdom + your talent, our bets are covered from the start. By 1984 we’ll be making $44,000 a month, and even Jimmy [Buffett] will be standing in line to get your autograph.

Let’s stop looking at this college gig as a foolish expense + start seeing it as an avenue to big money: a fine investment, with huge returns in the offing. Right? Yes. Let’s do it. Love, H.

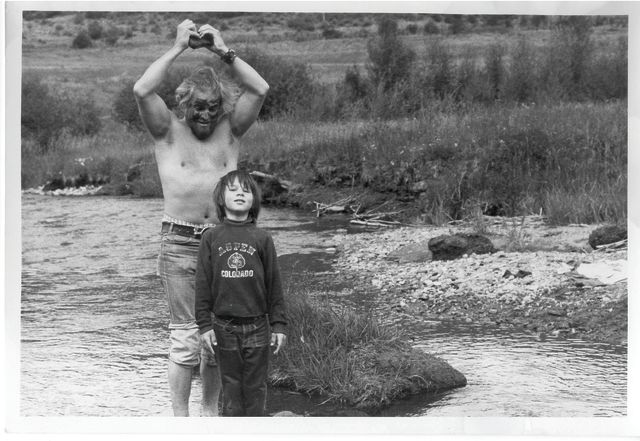

Image: Bud Lee

Sometimes apparently ordinary events or objects encapsulate vast realities. This letter is one. What is perhaps most remarkable is that I had completely forgotten about this letter until I rediscovered it during my research for this book. It is the letter I had been waiting for my whole life, a promise of an engaged father who gives advice, gives encouragement, promises adventure, affirms the good times, and talks of getting together soon. All of a sudden I had a father again. How could I have forgotten this letter?

However, we moved too fast toward a kind of intimacy that we both wished for but which did not yet exist. I took him at his word, plunged in and sent him a letter expressing my loneliness, sadness, homesickness, and depression. I wasn’t going to leave Tufts and retreat to Aspen this time, but it wasn’t an easy transition. I was exceedingly lonely, I didn’t know anyone and still didn’t know how to talk to strangers. Once again, after three years of being a part of a small and intimate community at CRMS, I was on my own. . . .

Some nights—or more accurately some mornings—Hunter would call. It might be two or three a.m., early by Hunter’s standards and time zone, but the very middle of the night for me. I would stagger out of bed and grab the receiver, and then go out into the hall to avoid waking my roommate. Mostly we would talk about nothing in particular—politics, Owl Farm, his current project. He would ask how things were going and I would give him a brief update. Sometimes we had business to discuss, such as the tuition payment. Sometimes I would slump to the floor and hold the phone to my ear with my eyes closed, dead tired, just wanting to go to sleep but grateful to hear Hunter’s voice and grateful for his reaching out to me. I see now he wasn’t calling to chat. We didn’t really have that kind of relationship yet. He was calling to find out how I was doing. The letters hadn’t worked as a medium, instead creating more confusion than clarity on both sides, so he called to check up on me in his indirect way, feeling things out from my tone of voice, what I did or did not mention. . . .

To cope with my loneliness at Tufts, I took long walks between classes through the neighborhoods around the school, and later throughout Boston. On weekends I would often walk down Massachusetts Avenue to Harvard Square where I would visit bookstores, see a movie, or just wander through the streets. At night I would plot out a destination on the city map, maybe the Charles River, maybe Harvard Square again, maybe somewhere in downtown Boston, and walk there and back, sometimes a journey of five or six hours through dubious neighborhoods. Other nights I would borrow my roommate’s car and drive out to Nahant, a tiny island just south of Marblehead that is connected to the mainland by a thread of a sandbar. At the tip of the island is the Northeastern University Marine Science Center. I would walk over the dunes and out onto the jagged boulders at the water’s edge, where I could see the lights of Boston about five miles away and watch the waves crash against the rocks. Other nights I would climb up the fire escape on one of the tall old buildings on campus to a little platform just below the roof. It was about five stories, and the campus was built on a hill, so from my perch I had a sweeping view of nighttime Boston.

Standing on the rocks at Nahant, or sitting on that platform, I had solitude, but not loneliness. I had the pleasure of my company, though I did dream, in a vague romantic way, of sitting there with a beautiful young woman. The night was a thick, warm, and intimate cloak that hid and protected me. At those times I imagined myself a brooding, deeply sensitive soul separated from his peers by a deeper understanding of life...

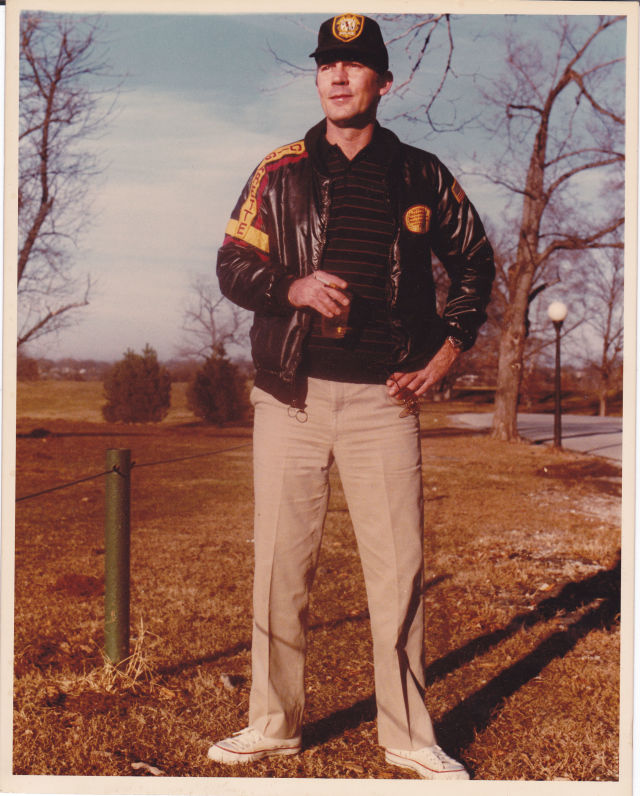

Image: Anna Steadman

If the night was a cloak in which I could hide, daytime was nakedness and shame. I felt exposed, seen, and judged by everyone around me. I could not walk down a sidewalk or a street with other people without a profound sense of awkward self-consciousness.

If I had solitude at night, I had raw loneliness by day, emphasized, or perhaps made possible, by the presence of all the people around me with whom I could not connect, not because I was aloof and made of a finer stuff, but because I didn’t know how. The time during class was manageable because there was no expectation of socializing. It was the time between classes, or during meals, when people talk to each other, that my isolation was so excruciatingly obvious to me.

Mealtime at the dormitory was the worst. All those people, all that talk, all those connections around me in which I had no part. It was unbearable to eat alone with no distraction. I would eat as fast as possible and still the meal seemed to take hours. I solved this problem by getting a subscription to The Boston Globe and reading the paper during meals, just as I had read Tolkien at Concord Academy a few years earlier.

It was in this state of mind that I wrote this letter to Hunter, full of disdain for the people around me, a disdain and arrogance born out of loneliness and fear.

Sept 4th, 1982

Hunter,

Yes—naked and alone in Boston. How baffling this is. “I’m not like the others!” The glum reaper is devious this time. He hides outside the window, the tip of his scythe barely visible. Thankfully, he doesn’t show his miserable, despairing form, but I know he’s there. Other times he’s not so subtle. He and I walk side by side, completely alone, so close I can smell the tears, the utter hopelessness of this endeavor. He shows me memories, vivid nostalgia, better times. It’s deadly, and very painful. And then, he retreats, I am reprieved, he never lets me forget he is there, though. Devious, insidious. I feel the best I’ve felt since I’ve been here. As I write this, light glints off the blade of that scythe, moves a bit farther out . . . It’s true, I’m not like the others. I’m quiet, “weird,” solitary. What can I say? I’m sure there are, among Tufts’ 5000 students, at least a hundred people with whom I can make friends, but they are as invisible as I. The social codes are different, distinctly preppy, fraternity-sorority, hip, flip, fast-and-cute, nauseating, and artificial. I have no doubt that the majority of these people are interesting, likeable, intelligent people. Unfortunately, they’ve been taught not to show it. The problem lies in socializing. When these people socialize, they don a common “mask.” They talk a certain way (hip, flip) act a certain way, do certain things, all of which have been defined as socially acceptable. By acting in such a way, one makes “friends.” With time, friends use their masks less and less, and a true, deep friendship results. But the mask is so cheap, and repulsive! I don’t want to use it, so I take the alternative (which is not necessarily best) and retreat, becoming quiet and “unsociable,” waiting to meet someone like me. Lonelier. The price of principles. The price of a progressive, Aspen, western education. The Community School. I’d do it a thousand times over.

Tried calling you tonight—no answer. Play? You’re right about the sense of humor. The Ultimate Weapon. Unfortunately, humor seems so far away when I most need it. I’ve made a sign, “Naked and Alone” . . . which I’m putting on the wall. Perhaps Tufts isn’t the place for me, perhaps the east isn’t the place for me. Nevertheless, I’ll definitely plan to stay a year here, to make a fair judgment. No Concord fiasco, I’m more sensible than that. Yeah, it’s easy to say that behind “His” back, but when he’s beside me, it’s hard…

My phone number is: 617 628 2043

Please call anytime. I really enjoyed your letter, thank you, it helped. Get some work done. I’ll be working hard here. Fear is in the air. These people would rather be at Harvard. Old Harvard. These people will be running this country. Not me, I’m not like the others, I won’t be. Never! …

A year here may be long enough, or just the beginning.

Remind me, Keep me honest, my objectivity can be easily

lost here.

Enough!

I love you, Dad.

Juan

When I found this letter to Hunter in the archive, I also found his notes that he had scrawled on the letter:

Yeah. “they’ll (sic) all gay like me—why won’t they admit it?”

Jesus. What hath Sandy wrought?

No college will cure this problem—only postpone it, for

$1500 a month.

That would pay the mortgage on the Owl Farm.

I have already paid $5000. Another $1000 due on Oct. 1st.

Can Sandy take me back to court if I don’t pay?

So what? He’ll be in the Village by then.

A few weeks later Hunter replied with a rambling, confused letter in which he recounted a story about the last time he received such a letter in which a friend of his informed him that he was gay and was going to New York City “to be with his people.”

Hunter wrote that their friendship petered out after a few get-togethers, not because of Hunter’s hostility to gays, but because they now had different interests and social circles.

He finished the letter with this:

...there is a knotty kind of intensity in your message that was exceeded only by its obscurity. So I figured I’d just skrike out in the fog and see what came of it. None of my doctorates gave me wisdom in areas like these—but I sense something heavier than just college on your mind and I think I should know what it is. Tell me.

I had written him two long letters explaining how lonely and unhappy I was and his reaction was to tell me I wasn’t being clear and to state the real problem. I had asked my father, who in his previous letter had been so supportive and welcoming of communication, for help or understanding, and now he was no help at all. In fact, his letter brought up uncomfortable questions: Did my father think I was gay? Was he saying that we would drift apart if I were? What was he trying to say? Did he understand me at all? Clearly he could not help me.

That first letter from Hunter was beautiful wishful thinking. He wanted to believe we had that kind of relationship, as did I. We wanted to believe we could start over from that moment and he could be the father he and I both wanted him to be. My letters to him exploded that illusion, and now I see he had no idea how to handle this kind of appeal from me. He could give practical advice; if I had asked him for help getting a job, getting a car, getting an interview for an article in the student paper, that he could have handled. But a cry of loneliness in the darkness, that he could not handle.