Tumult in Tin Can Alley: The History of the Hannums’ Rocky Love Story

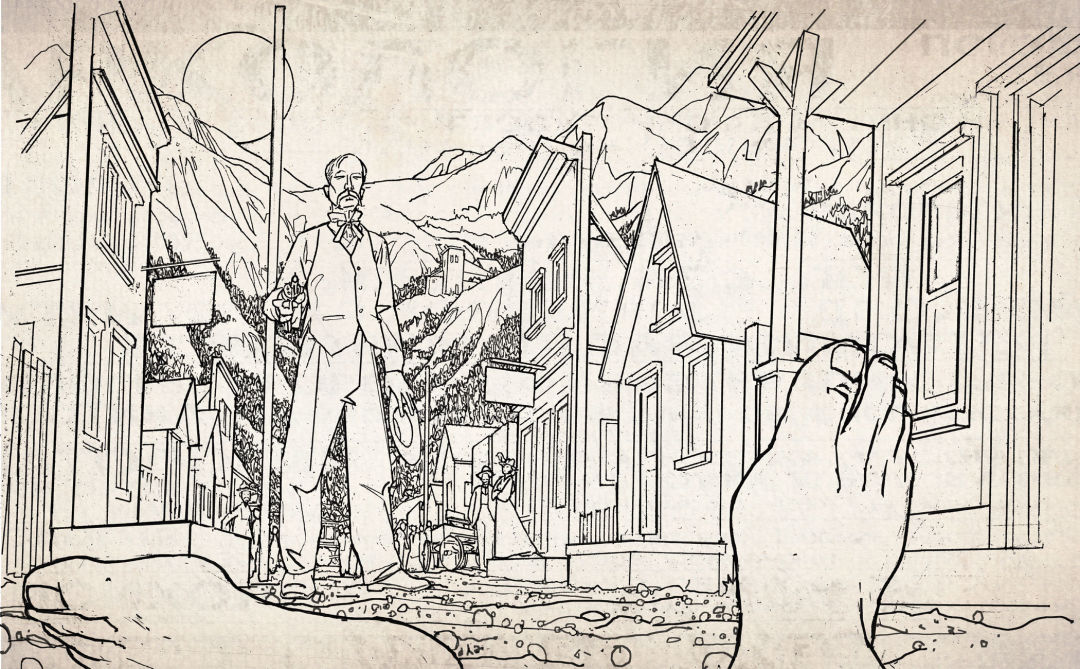

Image: David Johnson

On a crisp predawn morning in the late summer of 1895, James “The Icicle” Hannum, the tough-minded proprietor of Aspen’s Brick Saloon, burst through the front door of Lou Fuller’s three-room house of questionable repute on Deane Street. Her trackside dwelling was in the bawdy district of town known as Tin Can Alley, between Mill and Galena Streets. Hannum, with a .41 Colt revolver beneath his coat, was looking for his wife, Ida, supposedly inside with another man.

Following him from the Brick (now the Red Onion) were his poker-playing associate Fred “The Mysterious Kid” Gillette, who had cautioned Hannum not to go, and known “fallen women” Grace Mullins and Gertie Mason, who had egged him on. Inside the house were Fuller, Kitty Holmes, and Ida Hannum, along with Fred “The Swede” Johnson, who occupied a bed in the middle room. During the ensuing melee, two shots were fired.

Johnson, described in newspaper accounts as a burly young man, took a slug to the left of his breastbone yet managed to stagger out the front door clad only in a shirt, leaving a trail of blood behind. James Hannum, the other occupants of the house, and assorted witnesses fled the scene.

Deputy Marshal William Welch heard the shots from Cooper Street and rushed toward the sounds. Along the way, he encountered Mason on Durant Street, who told him, “I’ll tell you who done the killing: it was Icicle Jim.” He found Johnson, near death, along the Midland railroad tracks on Deane Street (opposite where the Hyatt Grand Aspen now stands). Welch lit a match to see the face of the victim, who could not utter any last words, then sent for a doctor and the coroner.

Image: David Johnson

Police Captain J.M. Williamson arrived on scene, and Welch went to the Brick and arrested Hannum, who had returned there and was coolly tending bar. Soon after, Williamson, in a kind of Wild West dragnet of the times, arrested Mullins, Mason, Holmes, Fuller, and Gillette as possible accomplices and/or witnesses who might flee.

The hardscrabble nightlife of 1890s Aspen carried different hardships than the carousing of today. Imagine calloused hands on soft skin, coal-smoked clothes, stale biscuits and bear-neck stew, drafty clapboard shacks with no running water, manure-strewn muddy streets, and ubiquitous barking dogs. Add in a lack of regulation and recourse for complaint, plus an abundance of whiskey, morphine, and prostitution, and you have Aspen’s historic “infected district,” where this tragic love story took place.

The characteristically blunt Aspen Tribune headline the next day, August 28, read “Fred Johnson Meets Death in a Deane Street Dive,” recounting starkly that “in a few minutes the unfortunate man was a corpse ... lying almost nude upon the ground.”

Much like Aspen’s scandals of today, the ensuing two trials, and the question of whether James Hannum acted in self-defense or justifiable rage, fueled gossip all over town. Between August 1895 and February 1896 the Tribune, Rocky Mountain Sun, Aspen Times, and Aspen Chronicle recounted the events in full.

Before Ida married Icicle Jim, said court testimony, the couple lived together on Deane Street, where she had formerly worked as a prostitute. Their troubled love—evidenced by their continuing relationship throughout the ordeal—along with the piquant details of the murder tantalized the town.

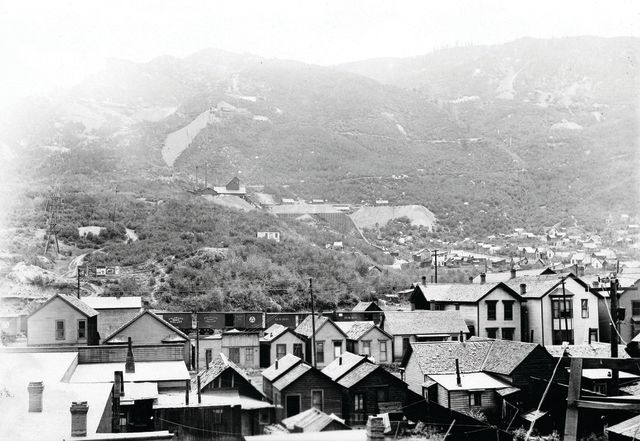

Image: Aspen Historical Society

There Goes the Neighborhood

In the early 1880s, Deane Street, named after Judge J.W. Deane, was Aspen’s main thoroughfare, and development rippled out from there. Because single women had few employment options and silver mining accelerated between 1880 and 1893, many “tabernacles of corrupt morality,” as the local papers referred to them, and smaller “cribs” flourished on Deane and Durant Streets during this time. (Even if single, the women who worked at these places often added an honorific “Mrs.” to their names for a facade of respectability.)

The Sun reported in February 1886 that the designated containment zone for “frail sisterhood” stretched from Hunter Street to Galena. By July 1886, city ordinances made prostitution a finable misdemeanor. At the time of the murder, the city hall, jail, and fire station were between Durant and Deane on the corner of Mill, and Fuller’s house was several doors east.

With some 2,500 miners and assorted opportunists arriving by the early 1890s, Deane Street was the logical place for prostitution. Men getting off work passed the locale on their way home, where “unblushing women overtly advertise,” the Times wrote on November 11, 1888. So successful were these women that they built an economic force lasting through the 1890s that the city couldn’t quash. At the same time, one block away on Cooper Street, plentiful saloons and vaudeville theaters added more temptation.

But the arrival of the Colorado Midland Railway in 1888, after construction of a passenger depot, set the stage for conflict between the freewheeling frontier morality and the “respectable people,” some of whom had to run the gauntlet of Tin Can Alley to and from the depot (located near today’s Gondola Plaza). The Times further complained that “the first thing people see when arriving by train in the city is the sign of prostitution, the half-clad women standing in the windows and doors of the houses.”

This clash between frontier Aspen and an emerging new town led to more arrests under the until-then largely overlooked statutes against prostitution. Systematic fining of offenders created a turnstile effect that produced regular revenue without stopping the problem. Arrestees clogged the court and the jail—dubbed the “Hotel Bastille” by the papers, in reference to the infamous Parisian prison—yet the neighborhood flourished because prominent citizens owned the real estate and knowingly rented to prostitutes.

In one case, the Times on February 5, 1888, printed a letter from future Colorado governor Davis Waite, accusing the town’s mayor of renting a property to “colored prostitutes from Leadville,” opposite Waite’s rental house near Galena and Durant. He also insinuated that the mayor had influenced the police to leave them be.

And so it was that the railway’s arrival on the south side of town and into the “sporting district” created the first pressure on an Aspen neighborhood to upgrade, while savvy landlords garnered high rents and looked the other way.

Image: Aspen Historical Society

Not enough sand

With Aspen’s rampant prosperity having diminished by 1895, after the demonetization of silver in 1893, moral outrage over the still-flourishing bordello district gained more traction. As the lurid facts of the Hannum murder came to light, the town’s reputable faction pressed for reform while those profiting from prostitution became more conspicuous, and the struggle played out in the divided opinion of the populace as well as in the courtroom.

Aspen’s coroner, M. O’R. Hughes, convened an inquest and impaneled a jury the same day as the killing. James Hannum was subsequently charged with murder and underwent a preliminary hearing and trial in the Pitkin County Courthouse.

The fact that Hannum fired the second, fatal shot at Johnson was undisputed. The courtroom drama would center on which man had fired the first shot and which woman (or women) was sharing the bed with Johnson at the time.

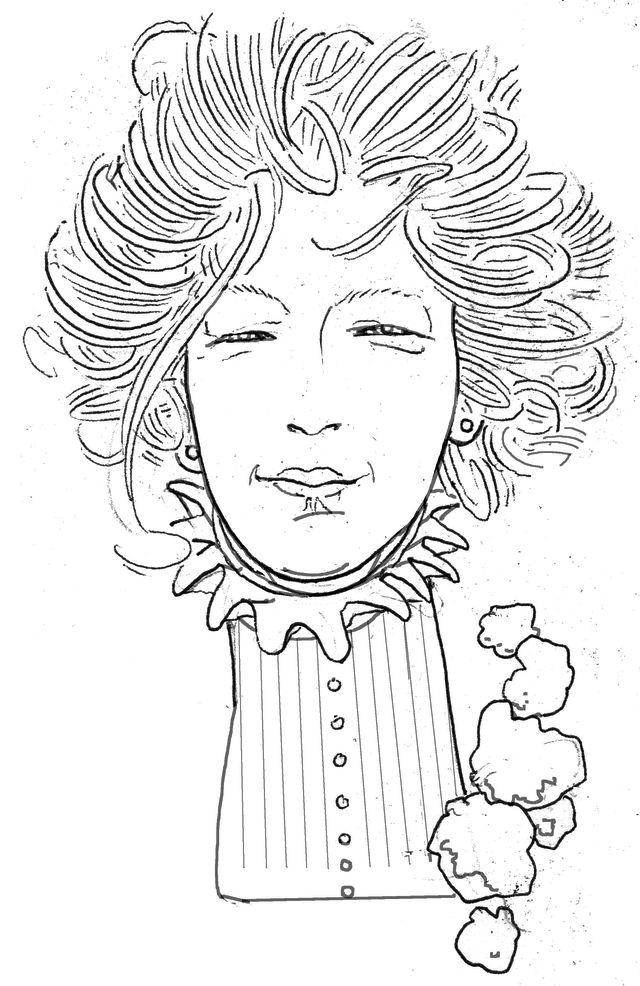

Though many facts conflicted, public sympathy ran in favor of Hannum due to his wife’s supposedly tainted conduct. Nonetheless, Ida Hannum was a supportive witness for her husband, even as the prosecution highlighted her past as a prostitute “troubled by a whiskey mania.”

Taking liberties that would be anathema in today’s legal system, a Times reporter conducted a jailhouse interview of James Hannum two days after the murder. In the cell opposite Hannum and Gillette, Mullins, Mason, and Holmes talked freely with the press as well. The reporter wrote that Fuller, who was also in jail, “had been taken with a fit, caused by her forced abstinence from whiskey-drinking. She saw snakes and Sheriff Hays removed her to her home on Deane Street.”

Hannum told the reporter that he’d hired attorneys, hoped for fair treatment from the press, and didn’t wish to make a statement. Mason, meanwhile, said she’d never told Officer Welch that Hannum killed Johnson, claiming that at the time she didn’t even know Johnson was dead.

Image: David Johnson

According to the Tribune’s September 12, 1895, report on testimony at the arraignment, Mullins, Mason, Gillette, and James Hannum were in the upstairs wine room at the Brick prior to the murder. Gillette testified that he heard Mullins incite Hannum to go to Fuller’s house, saying Ida Hannum was there with Mullins’s former lover. She goaded Hannum for “not having the sand” to address the situation.

Town was abuzz as to why Ida Hannum had not been detained, nor given her account of events, since she was the magnet that drew the crowd to Fuller’s house that fateful morning. While authorities were trying to locate her downvalley, the prosecutor said she couldn’t be interviewed without her husband’s consent.

A hearsay story in the Times a week earlier, on September 5, reported that Mullins hoped James Hannum would “pummel her derelict Adonis.” She then supposed that “her truant individual” might return to her afterward and she would then “give him the laugh in true half-world fashion.”

Instead, the plan backfired, as she and her friends were arrested as possible accomplices to a sordid murder. Moreover, her former lover was elsewhere that night. Thus, Hannum shot a potentially blameless man.

Yet the legal question remained: Was Hannum guilty of murder, manslaughter, or justifiable homicide? Did he shoot at his wife or at Johnson? Were his actions legitimized by his rage at seeing his wife—who said she’d been sleeping in the front room with Fuller—scramble for her clothes when he entered?

Courtroom drama

The coroner’s report in the Times on August 28, 1895, said that Johnson’s body lay in the morgue for several days and “the remains were viewed by many, including some women drawn by morbid curiosity.” A spillover crowd congregated at the Pitkin County Courthouse for Hannum’s preliminary hearing and arraignment on September 12, the Tribune reported. Defense attorneys E.C. Stimson, H.L. McNair, and G.E. Johnstone represented Hannum against prosecutor W.B. Wiley, with Judge James H. Leahy presiding.

Fuller testified that she had rented Johnson a room, that “he was a miner but seldom labored,” and that he endeavored to make a living through tinhorning—a saloon game in which three dice are dropped through a small tin chute onto a fold-out betting board. His wife was said to be sick in Glenwood, where he’d taken her some time ago. The Times also reported, on August 27, that Johnson had recently returned from Cripple Creek, where he’d been fined and briefly imprisoned for beating a laundry woman he lived with there.

The Fuller house occupants at the time of the murder—Ida Hannum, Holmes, and Fuller—and James Hannum’s followers—Mason, Mullins, and Gillette—told self-exculpating stories (though Ida’s testimony didn’t occur until the trial weeks later). The prosecution tried to build a case that James Hannum fired both shots, while the defense underscored the witnesses’ inconsistent recollections during cross-examination.

Because the middle room where Johnson slept was completely dark, it couldn’t be ruled out that he shot first. Yet only Hannum’s gun was found. Holmes and Fuller said that Ida Hannum had not been in bed with Johnson, but that they’d all shared whiskey with him before the women went to sleep in the front room. The defense pushed for acquittal, claiming that the women’s prior court histories cast doubt on their credibility.

The Tribune reported that James Hannum looked “decidedly haggard and confinement was having a telling effect on his health.” He pleaded not guilty and his bond was set at $25,250 ($684,000 at today’s value), which he somehow produced in several days. Mason, Mullins, and Gillette remained in jail, unable to raise bail. The trial was set for October 25 with another judge.

At the trial, witness testimonies were still inconsistent. There was consensus that conviviality took place upstairs at the Brick and that “the women wrought Hannum into a jealous frenzy,” the Tribune wrote. Mason played the piano while Mullins told Hannum, who was playing poker with Gillette, “If you knew where your ‘mama’ was you’d have reason to kick.” She also related that his wife had been trying to sell his diamond stud. They’d had “three or four drinks,” Hannum would later testify.

The Tribune detailed how Fuller, the first witness for the prosecution, said that she, Holmes, and Ida Hannum were asleep in the same bed in the front room and that Johnson was asleep in the middle room when James Hannum’s group arrived at 2:30 a.m. Holmes and Ida ran out and “Jimmie Hannum shot at them, saying to Johnson, ‘I’ll give you a dose, too, you’ve been sleeping with my wife’ ... and then he shot him.” She added that Johnson had had nothing to do with Ida.

Holmes took the stand next, saying that she and Ida had come to Fuller’s house together earlier in the evening. “Had a racket at home so I went to Fuller’s,” she said. “Johnson was in the middle room, while I slept in the front room.” She testified that she didn’t see who fired the first shot, and that she and Ida Hannum ran out the back door.D

Dr. S. P. Green, who was with the coroner at the scene, told the court he’d found the man lying near the railroad track and that the fatal bullet had entered the left side of his chest. If Johnson had fired the first shot, the defense implied, then a second shot fired by Hannum would have logically entered Johnson’s left side as he rose up in bed.

Mullins, who testified next, admitted she was very drunk when they left the Brick for Fuller’s. In the Times’s October 26 account, Mullins said she told Hannum that his wife was at Fuller’s house with Frank Bruin, a miner and noted young fighter about town, whom Mullins called “her papa.” The defense drove home that she, not Hannum, had proposed going to the house.

Mason, who had been in the paper previously for stealing a trunk of clothes from another prostitute and recklessly driving a carriage in the West End, came next. She recounted not seeing who fired the shots but noticing a woman in the middle room, adding, “She had on a chemise, but I didn’t see her face.”

Gillette testified that Mullins told Hannum “his ‘mama’ was out, also her ‘papa.’” The prosecution asked, “Was that not her papa, Frank Bruin?” Gillette responded that he didn’t know, only that he heard two shots but didn’t see what happened, and that Johnson then ran by him after the second shot. He added that Hannum said, “‘Come on, let’s go downtown; I guess I got myself in trouble.’ Then we passed the wounded man, but didn’t stop to see if he was hurt.”

After Gillette’s testimony, the prosecution rested, and the defense presented its case. The lawyers, maintaining that Johnson had fired the first shot, called Ida Hannum to the stand. The Tribune reported that she had a “nervous, hunted look,” while James Hannum “kept his head bowed, at times looking at the jury.” Under a rapprochement, Ida had been living in their home at 130 West Hyman since the shooting. She told the court they’d married in 1891 and that the last time she saw her husband before the shooting was two days prior.

She allowed that some nights she stayed at Fuller’s house and that she suffered from “whiskey mania.” She testified that she and Holmes went to Fuller’s house the afternoon of the murder and found Fuller in bed with Johnson; that evening, she drank whiskey in the middle room with Fuller, Holmes, and Johnson, then went to bed in the front room. With her husband’s sudden arrival early Tuesday morning, she said, she retreated to the middle room to put on her clothes.

She then recounted that Johnson sat up in bed and said, “If anyone comes into this room they’ll be killed.” She heard a shot, which she thought came from the bed, and saw her husband stagger as if he were hit. Frightened, she ran out the back door to taxidermist “Rocky Mountain Billy’s” house.

The prosecution attempted to discredit Ida by getting her to affirm a recent arrest for drunkenness at Breigar’s Saloon on Cooper Street, a dustup at Sander’s Brewery over the Fourth of July, and an incident in which her husband kicked in the door of Victor Little’s cabin, where she was drinking. Nonetheless, she testified, “No other man has ever figured in our troubles.”

Image: David Johnson

FRONTIER-ERA FORENSICS?

Evidence showed that a bullet (presumably the first) was lodged in Fuller’s backyard fence, 13.5 inches off the ground. This could have been the trajectory from Johnson’s bed in the middle room, or it could have come from where James Hannum stood, depending upon differing accounts. No gun was found in Fuller’s cabin or in Johnson’s clothes, though the defense noted that “many had passed in and out of the place” that day.

Hannum came to the stand in his own defense. He’d mostly lived in Aspen since 1881, furnishing money for mine leasing and going into the saloon business. Besides leasing the Brick, he owned a saloon in Tourtelotte Park. He said he didn’t know Johnson. During drinks at the Brick before going to Fuller’s, he told Mullens that his diamond stud was still in his possession and that he doubted his wife was with another man—yet Mullens compelled him to go. At this point, Ida Hannum and her mother, who was up from Denver, “both became hysterical with sobs.”

At Fuller’s, Hannum testified, Mason knocked. Upon entering, he heard his wife call his name and he followed her voice into the dimly lit middle room. Upon seeing her there getting dressed, he said, “Damn, I ought to kill you.” He then claimed that Johnson rose up and fired at him from the bed. “I saw a big man bounding toward me and shot him in self-defense,” he said.

In summation, Hannum’s lawyers said the shooting took place both in self-defense and to defend the honor of Hannum’s family. The prosecution, meanwhile, maintained that Hannum fired both shots and that, given Hannum’s knowledge of his wife’s wastrel history, there was no honor left to defend. Johnstone, for the defense, concluded eloquently: “Mind cannot fathom the depths of the human heart. Men have united their lives with women of social outcast and have loved them as devotedly as other men loved the most pure and spotless wife.…We have evidence of a ball in the fence to show a shot was fired at the defendant.”

The prosecution countered that the bullet came from Hannum’s first shot. Per the era’s rudimentary forensics, only the weights of the two bullets—the one in the fence and the one found in Johnson—could be compared to see if they were from the same gun. The prosecution, however, objected to admitting this new evidence.

After 36 hours and 50 ballots, the jury came back with a six to six verdict, resulting in a mistrial.

TRIAL REdux

Three months later, a second trial took place.

In the interim, however, new information about Ida Hannum surfaced. The Times headline on November 11, 1895, read, “Women Buncoed Him.” The story related how Ida found a wife for her friend Rocky Mountain Billy. The wife, “divorcée” Emma Stitzman from Denver, was really Ida’s polygamous sister. After a grand wedding party just weeks before the first trial, Stitzman conspired with Ida and their mother, convincing her new husband to give her his cash savings and plated silverware for safekeeping. He never saw his treasure again. Despite this episode, Billy escorted Ida’s mother to the second trial in February 1896.

At the second go-round, Hannum’s attorneys hammered the self-defense argument, putting forth the scenario of a man whose honor had been wronged. Ida Hannum testified with more self-possession, the Tribune reported on February 5. This time she was sure that the first shot came from the bed, while admitting that her poor conduct was caused by liquor and that her husband had not suspected her of wrongdoing.

Surprise witness A. I. Gardner, an associate of the other women who was rummaged up by the defense, attested that after the first trial, Holmes admitted both she and Fuller had lied in their testimony. Holmes further related that she, not Ida, had been in bed with Johnson, contradicting her prior testimony. (She would later be charged with illegal fornication.)

Dr. F. L. Mollin then testified that he had examined Hannum’s hand after the shooting and found a powder burn, supporting the defense claim that Johnson fired first from bed, just nicking Hannum’s hand.

The Tribune reported on February 8 that after 24 hours of nonstop deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of involuntary manslaughter, which carried a sentence of up to a year in prison. The defense called for a retrial, but at sentencing, Judge Thomas Rucker imposed only one day in jail for Hannum and $900 in court costs, a lenient sentence that reflected the popular sentiment that Hannum had been set up.

After the trial, James Hannum continued running the Brick and later moved to Woody Creek while also taking an interest in a gold mine in Nevada. Meanwhile, the Times reported on May 2, 1897, that the “notorious Ida Hannum” attempted suicide by taking “a large dose of morphine,” just one week after separating from her husband and moving back to Deane Street. After stomach pumping and seven hours of antidotes, “she will probably recover.”

The Hannums’ rocky love story is a stark reminder that misdirected motives can drive events into a tangled web of unintended consequences. Change the settings, the names, and the dates, and we have not only a timeless Aspen story, but a universal one.