A Look Inside Colorado's Stunning Marble Quarry

A worker in the Lincoln Gallery measures the cut blocks of marble.

Image: Daniel Bayer

Stefano Mazzucchelli, quarry master at the Pride of America quarry, is big and friendly, and when he talks he leans in close, gesticulating grandly with his hands. “This, no good,” he says in halting, thickly accented English, as he points to what appears to be perfectly good marble.

“This,” he says, turning me to face a different wall and pursing his fingers together to emphasize the point, “Calacatta!”

Calacatta is, arguably, the single most sought-after grade of marble in the world. And it’s why Mazzucchelli’s employer, R.E.D. Graniti of Massa-Carrara, Italy, dispatched him a few years ago to Marble, the aptly named hamlet near the headwaters of the Crystal River, about an hour-and-a-half drive from Aspen.

From left: A worker repairs a cutting blade; no longer in use, the Washington Gallery produced marble for the Lincoln Memorial and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

Image: Daniel Bayer

Having learned his trade in Carrara, where marble has been quarried since the time of ancient Rome, Mazzucchelli immediately recognized the value in what was then called the Colorado Yule Quarry. Taking advantage of a thick seam of unusually pure marble high in a mountain southeast of town, the quarry started producing in the 1870s and provided the stone for the Lincoln Memorial and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Washington, D.C., and the Colorado State Capitol, among other monuments and buildings. Due to a metamorphic process unique to the area, the marble’s grain structure lends it an exceptionally smooth, luminous surface that makes it particularly coveted.

The original quarry, which had a huge staging area along a former railroad line on the valley floor, operated until 1941, but it then remained closed until 1990. After that a few owners operated the quarry sporadically, and with limited success, until 2011, when R.E.D. Graniti, through a new division called Colorado Stone Quarries, took over operations and ushered in the quarry’s current mini-boom.

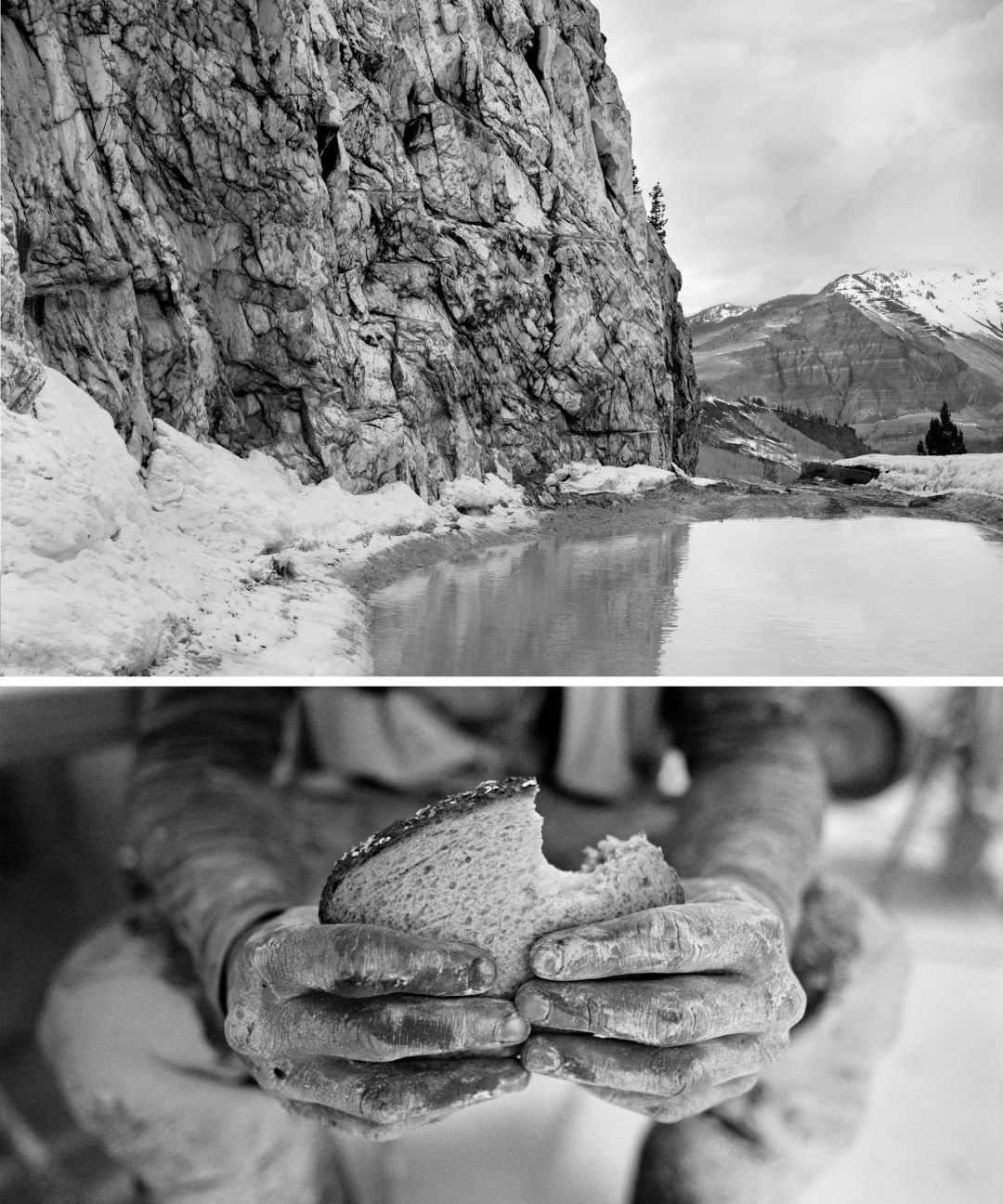

From top: A nearby pond helps keep water circulating through the quarry to keep saws cool and tamp down dust; a worker's hands are coated with marble dust as he takes a lunch break.

Image: Daniel Bayer

Using know-how and techniques honed through the centuries in Carrara, Mazzucchelli and general manager Daniele Treves upgraded the quarry’s equipment and vehicles to make them as efficient and eco-friendly as possible and last year closed the old quarry site (dubbed the Washington Gallery). In 2012 they had started removing stone from a new site just up the slope—the first additional access in over 100 years—this one named the Lincoln Gallery, with future expansion slated for what are being referred to as the Jefferson and Franklin galleries. In all, three grades of marble are being excavated from the quarry.

Today, the Lincoln Gallery, where I was granted a rare tour, has grown into a mammoth cave accessed by two portals. Inside, water from above and below is circulated constantly to cool the quarry’s saws and tamp down the dust, resulting in a thick, at times ankle-deep, white sludge on the cavern floor.

Along one wall, vehicle-mounted saws cut seams 10 feet deep into the marble before a diamond-studded chain is wedged in and run at high speeds, separating a piece of stone from the rest of the wall. In this manner, huge blocks of exquisite marble, averaging 22 tons each, are pulled out every day. The blocks are then trucked some three miles down a steep dirt road to the main office and staging area in town.

From Marble, most of the stone is shipped to Italy before R.E.D. Graniti processes and sends it to clients around the world. Recognizing the inefficiency, Treves says there are plans to build a processing center somewhere on the Western Slope.

The quarry itself will always be closed to visitors, according to Treves, but its bounty is on full display elsewhere, with huge, gleaming blocks of marble lying outside the main office, awaiting shipment to Italy and beyond. It’s an impressive reminder of the town’s main economic engine, but given the quarry’s history it’s fair to wonder how long the good times will last. Is there enough Calacatta for sustained quarrying? Unlike previous owners, is R.E.D. Graniti committed to maintaining the operation?

When asked how long he thinks the quarry might stay open, Treves shrugs and laughs. “A couple hundred years,” he says. “We made a big investment.”