A Complete History of Aspen Valley Land Trust, Colorado's Conservation Pioneer

Past where the pavement turns to dirt near the end of Snowmass Creek Road, the entrance to Harvey Ranch is unassuming. A rough, two-track driveway ascends steeply through a narrow valley lined with a riot of trees, ochre embankments, and sturdy fencing that ranch owner Connie Harvey explains is necessary to keep her cattle from scattering into the wilderness when they’re brought in for summer grazing.

In early May, when I visit the ranch with Harvey, ranch manager Todd Stoner is gearing up for a busy summer after having spent much of the long winter plowing snow. By the time 180 head of cattle arrive in June, he’ll have to have the fences fixed, the pastures ready, and the irrigation fine-tuned across the 1,800-acre property.

“It all hits at once,” says Stoner, who has been on the job for 17 years, often with just one summer helper. “It’s a mad dash to get it ready ahead of the cattle.”

We walk up another steep road to take in the views, Harvey and Stoner chit-chatting about livestock and grazing permits. Straddling the Snowmass and Capitol Creek valleys, Harvey Ranch provides a massive buffer between private properties dotting the rolling foothills and the timbered ridges and snow-covered peaks of the Maroon Bells–Snowmass Wilderness, with which it shares three miles of boundary.

Looking out at these untrammeled vistas and down toward the cluster of modest ranch buildings—which includes the original (though much-renovated) ranch house and a chicken coop from the late 1800s—it’s easy to imagine that the property looks much the same as it did 55 years ago when Harvey and her husband bought it.

That’s largely because Harvey, a matriarch of the local environmental movement, worked with Aspen Valley Land Trust and Pitkin County Open Space and Trails to place a conservation easement on the ranch in 2004. The easement extinguished most of the property’s development rights, which drastically reduced its value but guarantees that it’ll remain the way it is, in perpetuity. Harvey received tax benefits, as well as the ability to maintain the property as a working ranch, but the transaction was still very much a donation on her part.

“You could argue that it doesn’t make sense financially—the best way to make money would have been to subdivide it all,” says Harvey of her decision. “But it wasn’t about the cattle; it’s more about the land. I like the place. I like seeing the wildlife and the flowers.”

Aspen Valley Land Trust (AVLT) turns 50 this year, and its history is chock full of stories like Harvey’s, as well as many that are different. As the nonprofit has evolved from concentrating exclusively on parks preservation to protecting land for recreational assets, ranching, and, most recently, education—while also expanding its geographical reach—one thread has run through its tenure: adaptation to a rapidly changing landscape.

“There are so many different strategies for conserving land,” says Suzanne Stephens, AVLT’s executive director, naming easements on private land and the creation of parks and open space among the tools. “And it takes creativity and a lot of desire by the landowners to make it work. It’s a total community vision that involves a lot of puzzle pieces.”

Capitol Creek Ranch in Old Snowmass.

A Vision Is Born

In 1967, a group of Aspen citizens who wanted to protect some natural areas in their rapidly growing town formed two entities: the Parks Association planted trees and gardens, beautifying Aspen’s existing green spaces, while Park Trust (the precursor to AVLT) was set up as an independent legal entity to receive gifts of land and then manage them as public parks and open space. The latter was Colorado’s first land trust.

Though Park Trust received its initial gift that same year (the less-than-half-acre Freddie Fisher Park on Aspen’s eastern edge), land donations were generally few and far between during the first couple of decades. One exception: the cascade of gifts from Park Trust’s second donor, local rancher Henry Stein, who also helped found the organization.

Stein, a successful Chicago businessman who wanted to be a cowboy, bought a 500-acre cattle ranch west of Aspen in 1946. Finding his calling in ranching, he also loved to ski and was very civic minded, according to his daughter, Mary Dominick. These values nurtured a strong community-centric conservation ethos. Eventually Stein helped preserve huge swaths of land on eastern McLain Flats and on both sides of the Roaring Fork River between Cemetery Lane and the Aspen Airport Business Center (AABC).

The first piece of the puzzle was 1.5-acre Fisherman’s Park, donated in 1972 and named for the access it provided to the Roaring Fork. Renamed Henry Stein Park after its donor’s death in 1981, it is likely AVLT’s busiest property today, also serving as an access point for the Rio Grande and Sunnyside trails and for climbing at Gold Butte. Picnic tables and an open lawn invite users to relax and linger, listening to the gurgling river and contemplating the near-vertical walls of nearby Red Butte.

Stein followed with donations to Pitkin County of a bridge, trail easement, and riverside park near the AABC—all now bearing his name and accessing fishing as well as hiking, biking, and cross-country ski trails. In 1990, Pitkin County’s brand-new tax-funded Open Space and Trails (OST) program (backed by supporters of the Parks Association) inherited this ever-widening patchwork of conserved land around the hub of Stein Park (which Park Trust still held).

Later, Park Trust and OST would collaborate to protect several other parts of Stein’s ranch. And through the tools each offered—conservation easements and open-space designations—Dominick, who ran the ranch until the early 2000s and continues to live on part of it, was able to continue her father’s legacy, even as most of the property passed on to new owners. “That was my parents’ dream,” she says. “They wanted to leave as much green space as possible close to town, and they never wanted credit for it.”

Today, just a handful of homesites are discreetly clustered on the historic ranch, while commuters driving along eastern McLain Flats Road to Cemetery Lane enjoy mostly rural and wild vistas. Also, three different trails—Stein, lower Sunnyside, and Red Butte—are available to the public, all surrounded by protected land.

Meanwhile, AVLT (which changed its name from Park Trust in 1992) had now found one of its most reliable and enduring partners in Pitkin County Open Space. Aside from sharing DNA, the organizations could focus on their strengths—AVLT on accepting easement donations and the county on purchasing land for recreation—while teaming up, when feasible, to provide a double layer of accountability. In other words, while open space can be secured with tax dollars and often provides a public benefit, the addition of a conservation easement provides the teeth in defining and implementing land protection. “By co-holding an easement, we’re increasing the insurance that 200 years from now, one of the entities is going to be on the ball,” says Dale Will, acquisitions director for OST. “It adds a safety net to the whole process.”

Harvey Ranch

Greener Pastures

When Park Trust began its work, conservation easements—deed restrictions landowners place on their property that limit or eliminate development rights—were about as little known in Colorado as land trusts. In 1978, local resident George Stranahan donated the first conservation easement in Colorado, on 543 acres of mining claims around Lenado, to the national Trust for Public Land. (The easement was later transferred to Park Trust.)

That was right around the time the federal government began offering tax benefits for conservation easements, and, three years later, Stranahan followed up with the first conservation easement negotiated directly with Park Trust, on his Flying Dog Ranch near Carbondale. At the time, Stranahan was gradually transferring ownership of the ranch to the McIntyre family, who still live on and manage the property, and he wanted to ensure that the land would remain further undeveloped.

Like Harvey and Stein, Stranahan, who has by now helped preserve nearly 900 acres in the Roaring Fork Valley through conservation easements, also believes in the inherent value of open land. His philosophy is neatly encapsulated in the forward of AVLT’s book Our Place: “Land is more like your children; they are my own, but I do not own them.”

Still, conservation easements didn’t work for everyone. Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, farmers and ranchers faced ever-increasing threats to their livelihoods from rising real estate values and potentially crippling inheritance taxes. Federal tax write-offs weren’t enough of a benefit for agricultural producers who didn’t make much money in the first place.

A new benefit came in 2000, when Colorado enacted a conservation tax credit that put cash into landowners’ hands. Combined with a merger with the Western Colorado Agricultural Heritage Fund three years later, AVLT now had more tools and resources than ever for preserving ranches and farms.

One local ranching family in Old Snowmass was able to draw on the new tax credit and other development incentives to preserve their property in a deal that broke new ground for local conservation efforts. Since 1961, Bob and Tee Child, along with their six children, had been running cattle on their Capitol Creek Ranch. Bob was also a leader in the local conservation movement, first fighting off development of a proposed ski area on nearby Haystack Mountain, then helping get the surrounding area designated as wilderness and pursuing numerous growth-control measures as a Pitkin County commissioner and member of the planning and zoning board in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. He had also studied the nation’s first agricultural land trust with the intention of pursuing something similar locally.

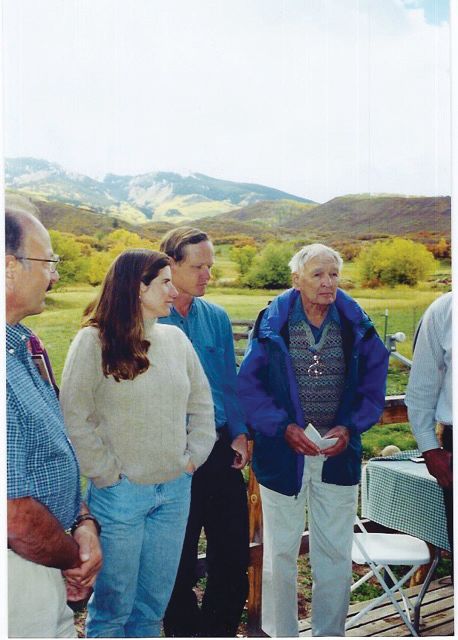

Bob Child (right) at the signing for a conservation easement on his ranch in 2002.

In figuring out how to pass on the ranch to their children, limiting future development was a priority, according to Steve Child, Bob’s son. His father “thought that this land by rights belonged to the Ute Indians, and it wasn’t a commodity to be bought and sold. He thought, ‘you’re a caretaker of the land, there will be somebody after you, and you want to leave it in the same way for them.’”

But even for one of the valley’s most conservation-minded citizens, the math wasn’t adding up. The children wouldn’t be able to afford to keep the ranch. Steve, now a county commissioner himself, says that most of the farming and ranching families he knew from growing up here eventually sold their land to developers.

After several years of negotiations with both AVLT and OST, a solution was finally found, and in 2002, just months before his death, Bob Child signed papers that set the agreement in motion. Today, nearly 1,500 acres of the ranch is sterilized from development, part of a complex, $3 million deal with the county and AVLT. Seven homesites were created to cluster development in a small area near Capitol Creek Road, and the family was authorized to sell transferable development rights (which convey the right to develop from rural areas to more appropriate, populated areas). The Open Space and Trails department purchased the conservation easement, which it holds jointly with AVLT.

“In terms of protecting the land for generations to come, I’d say for sure it worked the way my dad envisioned,” Steve says of the deal. “There will be changes on the ranch, but they will be minor. I only see a couple new houses in coming years. Most of the ranch is really remote backcountry, and it’s going to stay the same forever.”

For several reasons, all of the children except Steve, who continues to raise and graze cattle on his portion of the ranch, have since sold their lots. But OST inched closer to its long-term goal of protecting the ranches of the Snowmass–Capitol Creek drainage, and the much-touted deal set a precedent for AVLT.

Capitol Creek Ranch became the local template for preserving large ranches. According to Dale Will, Connie Harvey came forward immediately afterward asking for the same deal. The following year, a $3 million conservation easement, funded by OST and held by AVLT, was placed on her ranch. Together, the adjoining Child and Harvey ranches represent more than 3,300 acres of permanently preserved land. Since then, several other local ranchers have followed their lead.

Eighth-grade students at Chapin Wright Marble Basecamp.

Lifelong Learning

With 50 years under its belt, AVLT can boast plenty of firsts. But recently, it again wandered into new territory: education.

Almost exactly as old as AVLT is the Aspen School District’s eighth-grade outdoor education program, which since the late 1960s has been using a rugged, aspen-tree-covered piece of land near Marble as a base camp for an annual excursion. For four days, groups of kids and chaperones backpack 25 miles through the surrounding wilderness, arriving at base camp via various routes. There, for three days, the students participate in activities designed not only to develop their physical skills but also to build traits like perseverance, grit, compassion, and empathy, according to Aspen Middle School Principal Craig Rogers.

A couple of years ago, school officials heard that the property’s owner—the third one in a row who had been informally allowing the school district to use the land—wanted to sell. Around the same time, a neighbor alerted AVLT’s Stephens, an Aspen native who had gone through the outdoor-ed program herself.

It was immediately clear to both parties what had to be done, and after raising $550,000 in grants and private donations, AVLT closed on the 47-acre property in June 2016.

Renamed the Chapin Wright Marble Basecamp, after a late outdoor-ed student whose memorial foundation donated to the cause, the property is protected by a conservation easement held jointly by AVLT and the Crested Butte Land Trust. The deal also guarantees public access to the North Lost Trail, which traverses the property.

Outdoor ed is “life-changing for a lot of people,” says Stephens, in explaining AVLT’s decision to secure the property as well as extend access to other schools in the area, too.

For the Aspen School District, which considered trying to buy the property but rejected it as financially unfeasible, partnering with AVLT was a natural fit, says Rogers. “It was the perfect connection between an organization in the community that greatly values land conservation and a school district who promotes our students to be lifelong learners outside of the classroom,” he notes.

From its origin as a grassroots group of citizens preserving parks, AVLT had come full circle, in a way, by acquiring its first property specifically designated for educational purposes. But, at close to 41,000 acres conserved over the past 50 years, that doesn’t mean the organization’s job is done, says Stephens. “[Even] when the last big ranch is conserved, we will always be part of the fabric of the network of green spaces,” she comments. “Our role has evolved from parks to big ranches to this community-minded piece with education. But we’ll always go out every year to make sure easements are being honored, form new partnerships, and maybe do more stewardship restoration of the land itself. And there will always be those key little parcels that matter to the community. We’re definitely here for the long haul.”

Aspen Valley Land Trust celebrates its legacy on Saturday, August 12 at "The Promise of Forever" 50th Anniversary Land Gala. For tickets and more information, visit avlt.org.

AVLT by the Numbers

170 number of properties conserved throughout the Roaring Fork and middle Colorado River valleys

40,837 acres conserved

90 miles of river and stream corridor conserved

9 properties (totaling 111 acres) AVLT owns outright

164 properties (totaling 40,726 acres) on which AVLT holds conservation easements

51 conserved properties (totaling 7,897 acres) that provide public access

31,196 acres of agricultural land AVLT has conserved

.14 size, in acres, of AVLT’s smallest property, Aspen Alps Park

2,063 size, in acres, of AVLT’s largest conserved property, Triple J Ranch along Garfield Creek in New Castle