The Genesis of Bauhaus and Why We Celebrate It in Aspen Today

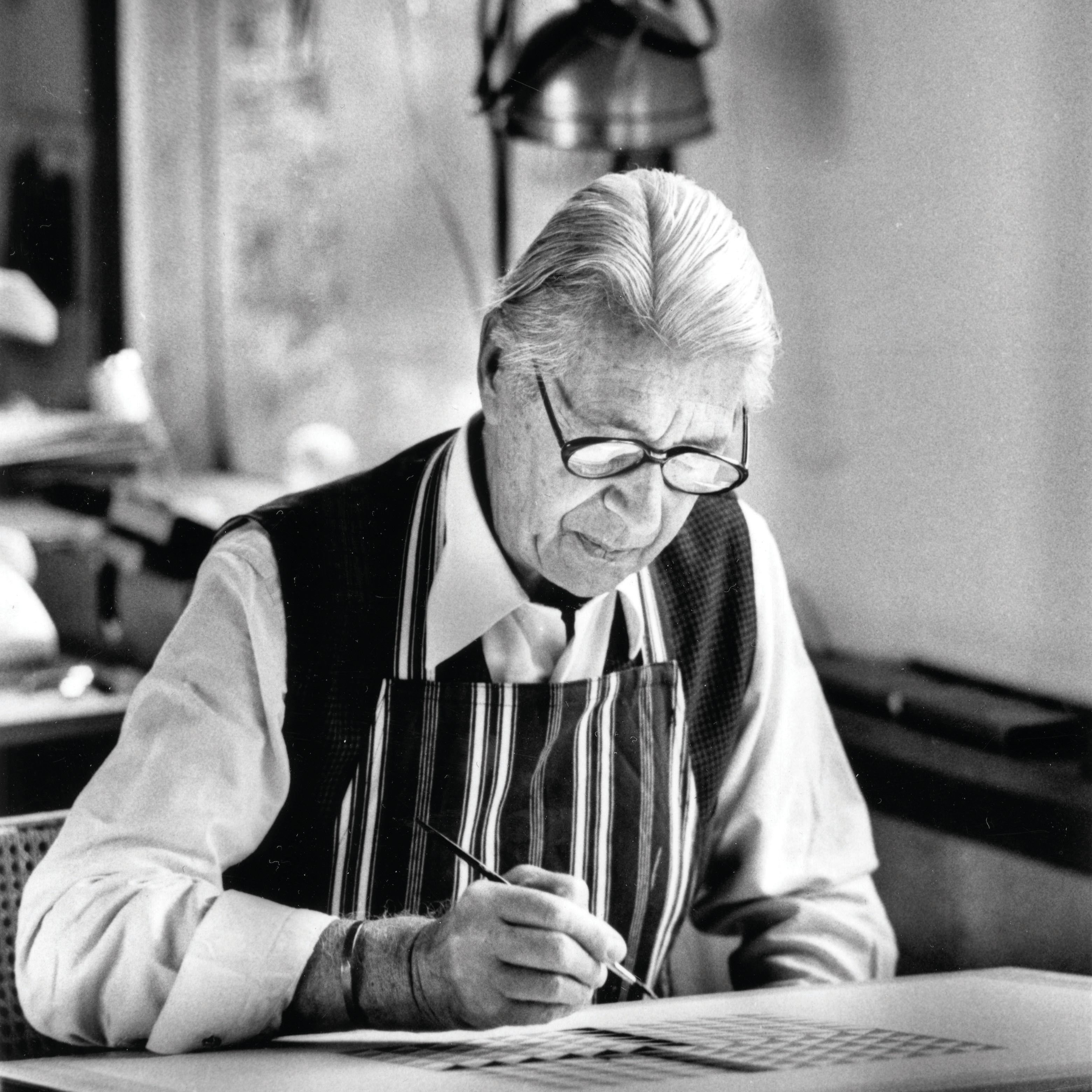

Friedl Pfeifer, Walter Paepcke, Herbert Bayer, and Gary Cooper at the Four Seasons Club in Aspen, circa 1955

AS: In a nutshell, what is Bauhaus?

LB: A modernist art school founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius in Weimar, Germany, after World War I. It moved to Dessau in 1925, to Berlin in 1932, and closed in 1933.

Gropius’s idea was to integrate art into all aspects of life. There was no hierarchy in the arts, he proclaimed, so there was no difference between fine art, craft, applied art, design, and commercial art. They were all considered equal.

There were really important principles that included functionality, practicality, and lack of ornamentation. The trends in the art world at the time were really gilded and baroque. The Bauhaus idea was to remove all that ornamentation and make art more functional and less frivolous.

One of the things that people associate most with the Bauhaus is architecture, but there wasn’t actually an architecture school at it until 1927.

The Bauhaus was known for a sense of play, too, wasn’t it?

This was an artist commune, with only 200 students. The students and the masters lived together, worked together, and ate together. There was a lot of camaraderie and a lot of joy. One of the important tenets became these really creative gatherings, which were primarily costume parties. The students were poor, the masters were poor, and it was a creative way to celebrate. They had kite festivals, lantern parties, solstice parties. There’s a great quote from [Bauhaus member Johannes] Itten, “Play becomes party, party becomes work, and work becomes play.”

Is there a more recent art movement with which people might be familiar that the Bauhaus compares to?

No. And that brings a larger question: Why did the Bauhaus have this impact? There were tons of art schools that had been very impactful, but one of the reasons the Bauhaus was so impactful was because it had such a short tenure. The Nazis shut it down because it was considered too Communist, too radical. And because so many of the artists were persecuted, most of the masters and teachers emigrated to different parts of the world. Because of that emigration, it was dispersed.

What about the Bauhaus appeals to you the most?

This idea of the integration of art into all aspects of life, that it shouldn’t be siloed. And I love the accessibility. I was in St. Petersburg recently, and everything is so inaccessible because it’s so overly decorated, so ornate. The Bauhaus is much more about getting your message across, with easily readable fonts or buildings that are focused on the internal space rather than the exterior design.

I also love the Bauhaus idea of not just replicating the past. This really informs what [Bauhaus member] Herbert Bayer did in Aspen. He was very insistent about not making Aspen a Swiss village. He didn’t want it to be a replication of something else.

Lissa Ballinger and Ann Mullins in front of Bayer's Kaleidoscreen at the Aspen Institute.

Image: Nick Tininenko

Tell us about the art tours that you lead at the Aspen Institute?

I do them monthly in winter and every other week in summer. It’s really about trying to invite people to the Institute. A lot of people who’ve lived here for years have never set foot on campus. One of the things is just to make them realize that although this is private property, it’s open to the public and it’s one of the most beautiful places in Aspen.My tour does a brief intro to Bayer and to the Bauhaus, then we visit the Resnick Gallery and walk around campus. I show how the Institute and Bayer are linked into the history of Aspen.

One of the things that I love talking about is the way that Bayer designed the campus. He wanted the administrative offices on one side so you would do your work and then you’d have to walk through Anderson Park and be refreshed as you go to the side of campus where you sleep, eat, and recreate. I also love the idea of having nature be part of everything. It’s so much of what Bayer and [modern Aspen founder] Walter Paepcke believed in, and this is also consistent with the Bauhaus. Everything is in reference and in deference to the natural environment.

Why is it important that Aspen celebrate the Bauhaus 100?

What I love about what we’ve created—our tagline is “our legacy, our future”—is the recognition that it’s not just the history that we’re celebrating but how much this school still influences contemporary architects, landscape designers, artists, and thinkers, and not just in Aspen. It comes out of this vision by Walter Paepcke and his selection of Herbert Bayer to move here in 1946. Aspen didn’t just evolve as a ski town; it primarily evolved as a cultural center. This is such an interesting part of our history that undeniably differentiates us from any other ski area or mountain town in the world.

The Bauhaus was an egalitarian movement, right?

It attempted to be. More than egalitarian it was accessible. “Egalitarian” sort of scares me as a word, because then it really does become political. That’s how the Bauhaus got pigeonholed as Communist. The second director after Gropius, Hannes Meyer, was then removed because he was considered too Communist. That’s when [Ludwig] Mies van der Rohe was put in, in 1930, as the third director. He realized that if he wanted to keep the school running, he had to make it completely apolitical.

I think Bauhaus members would have had some very pointed thoughts on the economic disparity in Aspen today.

Definitely. The other thing that’s interesting is that the Bauhaus was half women. In 1919, if you think about it, this was pretty phenomenal. It went along with the constitution of the Weimar Republic, which included equality for women. However, Gropius was very clear about keeping the women in certain roles.

I’ve been told that people who are familiar with the Bauhaus may have a limited view of it.

When most people think about the Bauhaus, they think of a Bauhaus style, which the school would have revolted against. They wouldn’t have wanted to be considered a style that everyone copied. They wanted to be constantly creating new things.

After the centennial, how can visitors still engage with the Bauhaus legacy in Aspen?

Our website is going to be the primary legacy. All of the events that happened will be documented and all of the research will be kept on there.

Bayer and Fritz Benedict designed the guest rooms at the Aspen Meadows.