The Bauhaus Legacy in Aspen

The Aspen Institute's Bauhaus-inspired Boettcher Hall, designed by Herbert Bayer

Image: Harry Teague

Wandering through the campus of the Aspen Institute is like being submersed in a Bauhaus world, where the integration of art, architecture, and design creates a complete aesthetic experience. Bold white roofs stand juxtaposed against a blue-black Colorado sky like billowing cumulus clouds. Neatly trimmed paths meander among shimmering aspens, whose mottled shadows dapple crisp gray walls. Compelling geometries and primary colors surprise at every turn.

Here in Aspen one can find a relatively comprehensive embodiment of the hundred-year-old German Bauhaus idea. Although a stark contrast to the rustic, informal, and occasionally messy built environment associated with the West, Bauhaus’s artistry and functional ethos—as well as its mischievous bohemian sense of fun—complement our spectacularly tumultuous mountain landscape.

Conceived by a bunch of rambunctious and talented architects, artists, and intellectuals in Dessau, Germany, after World War I, the school strongly influenced modernism with design principles that relate form to function. Bauhaus’s founders were young, idealistic, and bent on straightening out their world after the ravages of war. The machine age was cranking up full steam, and unlike the handcrafted objects to which consumers were accustomed, the new mass-produced furniture and household items were at best awkward and inconvenient, and, more frequently, ugly and soulless. Buildings, meanwhile, dripped with opulent decoration that flaunted vast discrepancies of class and wealth.

Too often, Bauhaus is perceived as just a mid-20th-century style, but more significant is its legacy as a philosophy of art and design. By combining the techniques and passion of fine art with the no-nonsense functionality of industrial production, Bauhaus inaugurated an approach to making things that was both revolutionary and fundamentally appropriate. Though it didn’t succeed in erasing class distinction, Bauhaus’s lasting principles of functional design have influenced everything from modern-day skyscrapers to smartphones, jumbo jets to toasters, typefaces to armchairs.

The gym at the Aspen Meadows

Image: Harry Teague

So how did this hard-partying German art school—founded to train artists and craftsmen to fill jobs in a struggling Weimar economy and lasting only 15 years—become so integral to Aspen’s shape and personality?

To trace the connection, we must go back to 1945, when Chicago industrialist Walter Paepcke and his wife, Elizabeth, first visited the sleepy former mining town. Infatuated with Aspen’s serenity and natural beauty, they envisioned it as a place where thoughtful and creative individuals—artists, writers, scientists, and successful entrepreneurs—could retreat from their busy lives to restore body, mind, and spirit, a concept that eventually became known as the Aspen Idea.

As a kickoff to their vision, the Paepckes and friend Robert Hutchins, president of the University of Chicago, conceived of a celebration to honor the bicentenary of German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. The 1949 Goethe Bicentennial Convocation and Music Festival featured important intellectuals of the time, such as Albert Schweitzer, José Ortega y Gasset, and Thornton Wilder as well as most of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra under Dimitri Mitropoulos. It attracted 2,000 visitors and proved so popular that, before it had even ended, the organizers started to plan subsequent events.

An annual summer music festival and accompanying school, the International Design Conference in Aspen, and the Aspen Center for Physics soon were joined by regular seminars at what was then known as the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. International cultural, business, and government figures came to town each summer, while Aspen was also becoming a winter destination for the emerging sport of skiing. Acts like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Ella Fitzgerald played at the Red Onion and the Hotel Jerome. No longer sleepy, Aspen was waking up.

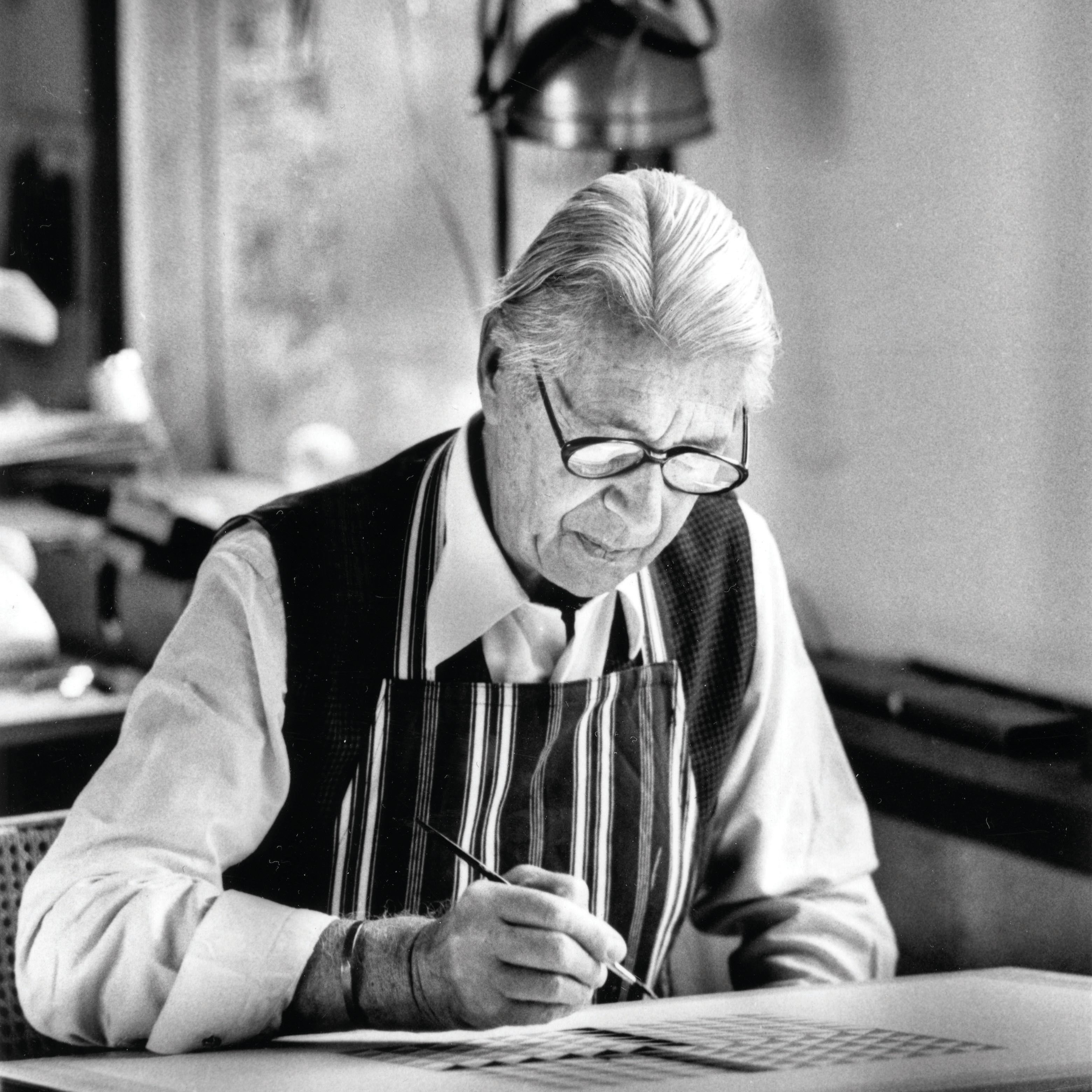

A design-savvy couple, the Paepckes were familiar with Bauhaus. As president of the Container Corporation of America, Walter had hired Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius as a consultant and American modernist Egbert Jacobson to head the company’s design department. He had also helped install Bauhaus photographer and teacher László Moholy-Nagy as head of the Chicago Art Institute. Unsurprisingly, Walter hired another Bauhaus star, Herbert Bayer, to oversee the Paepckes’ vision for Aspen, which included restoring the Wheeler Opera House and the Jerome, as well as designing structures for the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. In doing so, Bayer followed Gropius’s advice, stated at an Aspen town meeting in 1945, to “restore the best of the old, but if you build, build modern.”

Bayer's earth mounds at Anderson Park

Image: Harry Teague

Locals did not immediately embrace all of Bayer’s sophisticated, European-derived interventions. They loved things like the renovated starry sky on the ceiling of the Wheeler, but not so much the flat roofs Bayer favored or the white-and-blue exterior, with black “eyebrows” over the windows, that he had painted on the Jerome. But soon Aspen’s culture and recreation, not to mention its fun-loving bohemian lifestyle, attracted more-progressive residents who were more accepting of new ideas.

Aspenites subsequently began to take Gropius’s advice and “build modern.” New structures influenced by Bauhaus and also by Frank Lloyd Wright sprang up among the mining cottages. Local architects who had studied with Wright—such as Fritz Benedict, Robin Molny, and Charley Patterson—deferred to the spectacular natural landscape with organic forms and natural materials. Bauhaus-influenced architects like Bayer, Marcel Breuer, and Harry Weese responded more fundamentally to the colors of sky, snow, and trees, and to the sharp quality of the light. Wrightian houses abandoned traditional rooms in favor of informal, open floor plans. Those influenced by Bauhaus stripped away class-defining ornamentation, focusing instead on simple forms that responded directly to function. For instance, Bayer’s seminar rooms at the Aspen Institute were designed to eliminate hierarchy, with tables placed in octagons to give all participants equal status.

The bold spirit of these mid-20th-century builders resulted in the extraordinarily rich and marvelously eclectic cityscape that continues to shape Aspen today. A single West End block may include Victorian and Italianate cottages nestled up to midcentury modern classics and edgy contemporary homes. This aesthetic also happens to embody our town’s best qualities: adventure, progress, fun, tolerance, environmental awareness, and conservation.

Aspen owes a lot to the Paepckes’ broad vision of integrating art and commerce, inspired at least in part by the Bauhaus. By celebrating the movement’s centennial, we can ensure its perseverance locally as well as the continued assimilation of fast-paced modern technology and lifestyles into a humanistic environment for all of us.

The sgraffito wall

Image: Harry Teague