A Look Back at Politics in Aspen, Which Is Anything but Usual

Aspen has always enjoyed a high level of political involvement. If politics is "the art of controlling your environment," as Hunter S. Thompson declared, then engaging in it where you live only makes sense. As the national political conversation has become increasingly bizarre, it seems like a good time to take a look at some of Aspen's most unusual politically inspired incidents over the years, from an elaborate statue intended to garner support for the threatened silver standard in the 1890s to a meeting of world leaders a century later that turned into a vaudevillian comedy with tragedy lurking at its core.

Silver Girl

From the beginning, it was sometimes necessary for Aspenites to view local politics through a national prism. As long as the U.S. government based its monetary system on the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which provided price supports for silver, Aspen’s silver-mining-era economy was on solid footing. But in 1893, the Grover Cleveland administration came under increasingly intense pressure to switch to a strictly gold-backed system, and Aspen lobbied to keep silver in play.

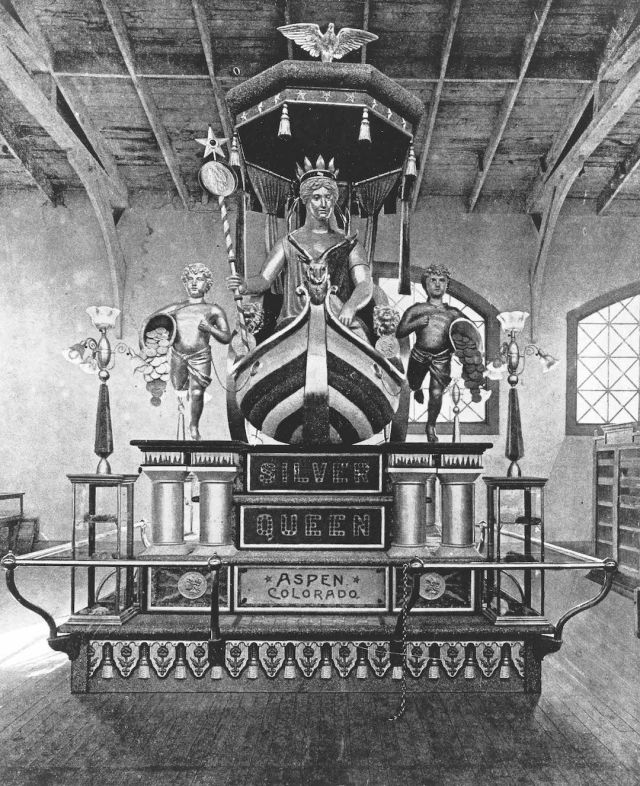

One tactic was to commission a “Silver Queen” statue that would be shown at the first-ever World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893. The hope was that the hordes of potential viewers, dazzled by its beauty, would persuade their elected representatives to maintain the dual standard for gold and silver. A weird long shot at best, the statue would stand as the first, but not the last, appearance of art as politics in Aspen.

The Silver Queen statue was commissioned for the World's Fair in Chicago in 1893.

According to the Aspen Times, it took 10 months under the direction of designer and sculptor Hiram L. Johnson of Pueblo, Colorado, to create an 18-foot-high queen riding in a barge studded with gold, silver, and gems. Elaborate silver trimmings included a buck’s head on the front of the barge and smaller figures of boys on either side, holding horns of plenty overflowing with dollar coins of silver and gold. Estimated to be worth $20,000 then, today she’d be priceless for her antique value alone.

The statue was crated in pieces and moved to the World’s Fair for display in July—the same month, by grim coincidence, that President Grover Cleveland sent legislation to Congress repealing the Sherman Act and demonetizing silver. The Silver Queen was eventually shipped back to Pueblo and shown until 1942, then supposedly shipped to Denver and never seen again. Whether stolen or mislaid, a statue designed to save Aspen couldn’t even be saved itself. But the star-crossed creation of the Silver Queen wasn’t the community’s last foray into national politics.

Think Globally, Act Locally

Fast-forward to the mid-1960s, when Aspen and the country entered one of the most turbulent eras in American political history. While generally very conservative, influential local political figure Dr. Robert “Bugsy” Barnard famously led a small crew who took chainsaws to every billboard in Pitkin County. Then he helped pass laws banning both billboards and neon lights in the county and the town.

On more substantial zoning and land-use issues, however, there was growing opposition to Barnard and his cronies. The policies they promoted would have allowed the upper Roaring Fork Valley to be carved up and sold in half-acre lots and would have allowed the construction of strip malls lining the highway. Also at issue were mounting complaints about serial civil liberties violations on the part of the local cops and courts.

The response was the well-documented Freak Power movement, initiated by author Hunter S. Thompson, which promoted activist lawyer Joe Edwards for mayor of Aspen in 1969. Edwards, beaten by just six votes, would be voted in three years later as part of a groundbreaking cadre of local county commissioners. In 1970 Thompson made his own run for office, campaigning for Pitkin County sheriff. He advocated tearing up the paved streets and promised to eat peyote on the job—and suddenly a little local election was being covered around the world. Thompson also lost narrowly, but broke trail for ultra-progressive sheriff Dick Kienast to take office in 1976.

Protesters line the meadows near the Aspen roundabout in August 1968.

When Aspen’s issues weren’t attracting national scrutiny, the community reacted in its own unique ways to the broader societal upheaval. In 1968, artist/activist Tom Benton led a march protesting the Vietnam War to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s house near Snowmass Village. The incident was well covered by local media, and not favorably. The real crime, it seemed, wasn’t a monstrous war on the other side of the world but trespassing at McNamara’s vacation place. (To his credit, McNamara came out and addressed the crowd.) Even the liberal publisher and editor of the Aspen Times, Bil Dunaway, wondered if it wasn’t a violation of an unwritten local law about not disturbing a celebrity’s privacy while here. Nonetheless, the protest clearly indicated that for national politicians, Aspen would no longer be a refuge. That fact would be echoed later during visits by the likes of John Sununu, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton.

In September 1969, when the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) decided to detonate a nuclear device underground near the current town of Parachute, about 50 miles from Aspen as the possible radioactive air pollution flies, it signaled the start of what is still an ongoing battle over attempts to extract natural gas from shale. Much of Aspen rose up to grill a group sent by the AEC to surrounding communities to explain to local “hayseeds” why intentionally setting off a 43-kiloton atomic bomb that would permanently irradiate the gas it freed was a good idea. Benton again, along with other concerned citizens including a contingent of Aspen High School students, staged a march at the site during the test, which was known as Project Rulison.

A small demonstration in the middle of nowhere didn’t stop the bomb from going off and rolling through the fragile shale within a few hundred yards of the Colorado River like a dryland tsunami. But it did help train attention on the area going forward, as one massive boondoggle after another has beset the region and its people in the search for so-called cheap energy.

"Sure, there was the Iraq-Kuwait situation, but it almost seemed liked he just wanted to get the hell out of crazy town."

Theater of the Absurd

Of all the strange politics that have engulfed Aspen over the years, probably nothing embodies “you can’t make this shit up” more than the Bush/Thatcher “war summit” in August 1990. When President George Herbert Walker Bush and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher came to town to speak at the Aspen Institute’s historic 40th annual symposium, it was a great get for the institute. It was also a big deal to locals who, depending on their politics, were either honored or aghast—or just annoyed at the inconvenience.

The event was a combination of the slapstick and the potentially dangerous from the jump. An extended meet-and-greet with Bush at Sardy Field was threatened when Secret Service agents spotted a silver van, the sun reflecting off of it, parked high above the airport. They literally had it locked in their sights before local deputies could explain that it was just “Homeless Joe,” an Aspen indigent who was probably looking for a good seat for the show.

Fully secured, Bush was greeted by various dignitaries, including Colorado Governor Roy Romer, State Senator Sally Hopper, and then-U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom Henry Catto and his wife, Jessica, who hosted the president and the prime minister at their home in Woody Creek. Bush had already climbed into his limo to depart when Aspen Mayor Bill Stirling finally arrived, running, after being stopped a mile earlier by the cops controlling traffic. He made it past one Secret Service checkpoint, then dashed across the tarmac, only to have another agent decline to open the limo door for the mayor to make his official welcome.

Stirling pounded on the window, announcing that he had “come on behalf of all the people.” Bush, left with little choice, got out to shake hands and have what the mayor later described as a brief “rap.” Seriously. From this quirky encounter (Stirling would subsequently attend Bush’s speech wearing a pith helmet), the president was driven to the Catto residence, where he met with Thatcher and was to spend the night.

The planning for Bush’s stay in the area had already discomfited Hunter Thompson, whose residence was just down the road from the Cattos’. The Secret Service initially demanded that Thompson, who had once been vetted thoroughly enough to spend time in Jimmy Carter’s White House, leave his own home for the duration of the president’s visit. Since Thompson was just coming off of a heated battle with the local district attorney’s office wherein a machine gun had been discovered during a search of his house, this request was probably predictable. But all of those charges had been dropped, and Thompson asked his close friend, longtime Pitkin County Sheriff Bob Braudis, to intervene. Hunter was eventually “allowed” to stay at his home, but directed not to go wandering around outside with firearms while Bush and/or Thatcher were in residence nearby.

In fairness, no more gun-toting locals were needed at this point. Only two days before Bush arrived, more than 50 local and outside cops were dealing with a seven-day threatened suicide standoff on McLain Flats, where Charles “Bud” Wolcott had barricaded himself in his home (inconveniently located along the airport’s flight path) with what turned out to be 38 guns.

“The Secret Service let us know that they would handle it if we didn’t,” recalls Joe DiSalvo, the county’s assistant sheriff at the time.

“They told me, ‘We can turn his head into pink mist from 300 yards.’” Luckily, the sheriff’s office dealt with the situation bloodlessly, but it barely left time to freshen up and welcome the large security details from Britain and Washington, along with the legions of additional officers called in to assist. To complicate matters, Thatcher’s good friend and political ally Ian Gow had been killed by a car bomb in London barely three days earlier, heightening security concerns.

Then, unbelievably, only hours before the president arrived, Iraq invaded Kuwait, ratcheting up tensions even further. Several media outlets described Aspen as “command central” for the Western world’s response to what Bush called “a naked act of aggression.” Bush and Thatcher discussed strategy for handling the invasion before holding a joint press conference outside the Cattos’ house, which was broadcast globally on CNN. It was the beginning of what would become Operation Desert Storm and an ongoing quagmire that’s claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, according to most assessments.

When the Bush/Thatcher motorcade wound its way into Aspen for Bush’s keynote address at the Benedict Music Tent, an estimated 600 protesters and onlookers greeted it. Many in the crowd had gathered at the invitation of local eccentric Nick DeWolf, who provided food and blank placards and the paint to write on them—essentially hosting what an Aspen Daily News reporter described as “a catered protest.” (Where else but Aspen?) Hundreds of signs dotted the crowd; four young women wrapped only in towels carried a banner reading, “It’s a Bush Party” flashed the president’s car as it glided past.

What was amusing for locals was unnerving for the security forces, who feared a car bomb of the kind that had killed Gow, and the tension was palpable. Moments before Bush began his speech, a loud boom echoed off of the surrounding mountains, rattling the tent. Local authorities hurried to explain that it was only realtor/developer Hans Gramiger setting off excavation explosives on his property on Shadow Mountain. The Secret Service dispatched a helicopter to check out the site of the smoke plume, and the scene looked more like Beirut than Aspen.

Nerves were still frayed when another charge went off near the middle of the speech, with the loudest one of all coming just after Bush finished. The timing was suspect to those who knew the politically aggressive and cantankerous Gramiger. And coming as the blasts did during a saber-rattling speech many considered inappropriate at an institute where the focus is on humanistic studies, they seemed spookily appropriate.

Bush was rushed back to dinner with the Cattos and Thatcher and guests, but he bailed on plans to spend the night and instead hurried off to his C-20 Air Force jet to fly out before the Aspen airport’s curfew took effect (a curfew, incidentally, that had been waived for far lesser luminaries in the past). Sure, there was the Iraq-Kuwait situation, but it almost seemed like he just wanted to get the hell out of Crazy Town, and who could blame him?

Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet

The countdown to the 2016 presidential election is in full swing and already an incident from Aspen’s past has relevance. During the Christmas holidays the same strange year as the Bush/Thatcher meeting, Donald Trump paid a visit here that became sensationally overpublicized when his then-wife, Ivana, got into a very public row with his newest girlfriend, Marla Maples, on Aspen Mountain. Both had been brought to town by The Donald, who chose Aspen as the place to play out his own personal drama as publicly as possible. He soon divorced Ivana and eventually tired of Maples. Though there was nothing overtly political about the incident, it laid the groundwork for what has become one of Trump’s most vexing issues as he seeks the presidency this year: his seeming objectification of women, which many describe as misogynistic.

While nothing on the order of 1990’s events has transpired locally since, Aspen continues to be the site of some controversy. Two presidential election cycles ago, in 2008, Barack Obama, John McCain, and the Dalai Lama all came to town during the campaign, the latter two simultaneously. McCain tried to arrange a heavily politicized meeting with the Dalai Lama but was publicly rebuffed.

With Colorado now a pivotal swing state in Electoral College politics, and with the abundance of well-heeled political donors in Aspen, expect front-row seats here this summer as state and national politicians (Clinton and Trump will almost surely visit) troop through town. It’s already been a year in which presidential politics and local races across the country have been marked by a strain of insanity that beggars the imagination. And Aspen hasn’t even weighed in yet. Stay tuned.