Liquid Gold

ASPEN & THE COLORADO RIVER BASIN

Image: Courtesy: CDM

In the Roaring Fork Valley, a bountiful snowpack brings obvious upsides: happy skiers, booked hotel rooms, a ski town’s lifeblood vigorously pumping away. But the recreational importance is dwarfed by something far more fundamental: that snowpack is water. Look no further than California to see the value of a healthy blanket of snow—and the major consequences that can result from its absence. The water from Aspen’s surrounding mountains makes its way into the mouths of locals and visitors, but also over the mountains to feedlots on the Eastern Plains, multiple cities, and all the way to very thirsty California, who might send it back to us as an almond.

ASPEN & THE COLORADO RIVER BASIN

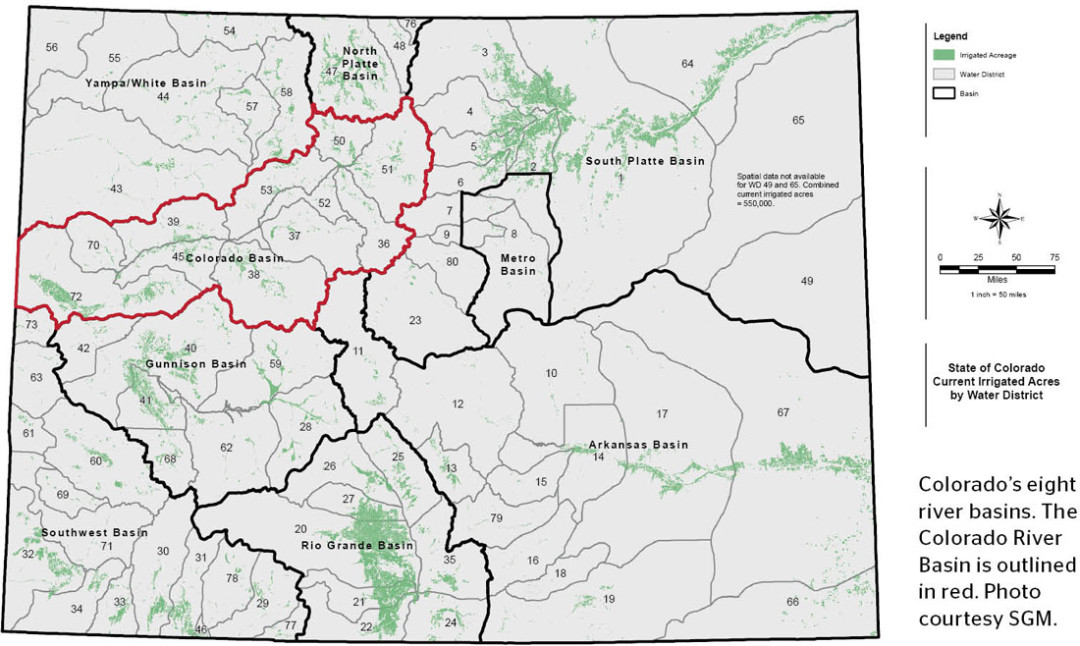

Aspen is located in the Colorado River basin, whose surrounding streams and rivers naturally flow into the Colorado River, the largest river in the West. There are eight basins in the state (the Metro Basin, while a separate political entity, is part of the South Platte Basin), but the Colorado River Basin generates the most water. It begins on the western side of the continental divide near Rocky Mountain National Park and ends at the border with Utah near Grand Junction. Dozens of transmountain diversions redirect water in underground tunnels from the Colorado basin to support Front Range cities like Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs.

A clarifier at the Aspen Water Treatment Facility eliminates turbidity by separating out physical particles carried in by Maroon Creek.

Image: Justin Patrick

ASPEN’S WATER TREATMENT FACILITY

“Better than bottled” is the motto for Aspen’s top-notch water treatment facility. The plant pulls water from Maroon Creek just a few miles below the iconic Maroon Bells; its water quality is 100 on a scale of 100, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. (55 is the U.S. average.) The facility’s biggest problem is turbidity—muddiness stirred up by the rushing spring runoff. After the water is corralled into vats, enormous clarifiers spin out the silt, sand, and small particles. Then it is filtered, treated, and stored in a protected underground reservoir. In summer, about ten million gallons of drinkable water is delivered per day to the City of Aspen.

Twin Lakes Reservoir stores water from Aspen’s nearby creeks and rivers.

Image: Mark Harvey

WATER TO THE FRONT RANGE

Since the late 1800s, infrastructure has existed to collect and divert water from the western slope—the land west of the Continental Divide—to the drier, more populated Front Range. Currently, about 600,000 acre-feet of water per year—that’s 196 billion gallons—are redirected through transmountain diversions to support urbanization and agriculture on the eastern plains. Two of the biggest diversions are located near Aspen. One is the Boustead Tunnel, which moves water from the Frying Pan River and Hunter Creek to Turquoise Reservoir. The other is the Twin Lakes Tunnel, which through a remarkable feat of engineering moves water from the Roaring Fork River headwaters near Independence Pass up and over the pass to Twin Lakes Reservoir. Both are part of the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, named for the two rivers and authorized in 1962 by President Kennedy, which primarily benefits Colorado Springs and Pueblo.

Lake Mead is held back by Glen Canyon Dam to ensure a controlled release of water resources, as well as to generate electricity.

Image: Courtesy: EcoFlight

WATER TO SURROUNDING STATES

In addition to meeting its own water demands, Colorado must deliver enormous quantities of water to the lower basin states of Arizona, Nevada, and California. The Colorado River Compact, signed in 1922, requires that the upper basin states—Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Utah—collectively deliver, on average, 7.5 million acre-feet of water per year. California receives the lion’s share, about 4.5 million acre-feet, which is more water than Colorado is entitled to by law. Colorado provides most of its share through the Colorado River, which flows into Utah and is stored in Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Higher average temperatures and weaker snowpacks in the past decade, combined with growing demand, are taking their toll: Lake Powell is currently at 51 percent of capacity, and Lake Mead is at 39 percent, its lowest water level since 1935.

The economic importance of water sports will be a focus of Colorado’s State Water Plan.

Image: Justin Patrick

RECREATION AND RIVER HEALTH

Keeping water in rivers is crucial to Colorado’s booming recreation industry. High flows are also critical for healthy aquatic ecosystems. Rafting, kayaking, fishing, and snowmaking are just some activities that require abundant water resources. Recreation generates an estimated $9.5 billion per year; reduced river flows are detrimental to business. For example, during the 2002 drought, recorded user days for commercial water-sports operations dropped by 40 percent. Balancing municipal and agricultural needs with recreation and environmental interests will be the central focus of Colorado’s first State Water Plan, a statewide policy initiative that seeks to guide resource decisions over the next decade. Agricultural use accounts for about 80 percent of water needs in the state.