The Story Behind 3 Quintessential Snowmass Ski Runs

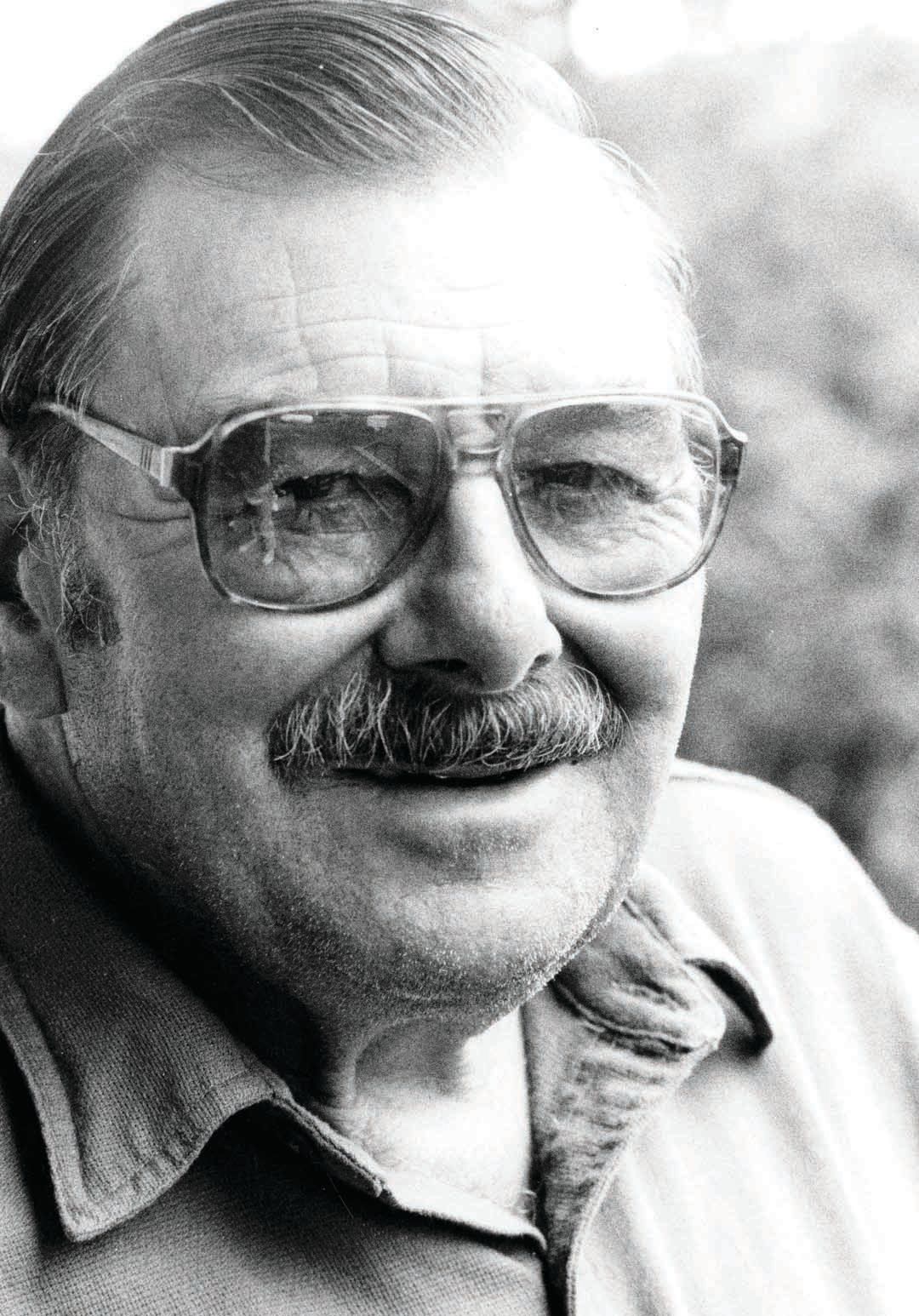

Jim Snobble leads a group of snowcat skiers in 1967.

Image: Aspen Historical Society

Sneaky’s

A spen ski instructor Jim Snobble had one of Snowmass’s first dream jobs. In the early 1960s, Aspen Ski Corporation (as it was then known) president D.R.C. Brown sent him to the Brush Creek Valley to investigate its ski potential. Those backcountry explorations led to a 1964 report for the Ski Corp that extolled the area’s promise, including its vast and varied terrain, favorable weather conditions, and—notably—appeal to expert skiers. The report convinced ski company officials that it was worth developing the ski area, and Snobble, who knew Snowmass like few others, became its first mountain manager.

Over 16 seasons, Snobble oversaw Snowmass with diligence, humor, and passion for the place and its people. According to current Snowmass General Manager Steve Sewell, he used to hide in the trees at the end of the ski day to see if patrol would spot him on sweep—earning himself the nickname “Sneaky.” When Snobble retired in 1984, the Upper Powderhorn run on the Big Burn, his favorite, was renamed Sneaky’s in his honor.

Sam Stapleton

Image: Aspen Historical Society

Sam’s Knob

A s a young teenager, Sam Stapleton spent summers near the base of what’s now called Sam’s Knob in a cabin with no running water or electricity, tending his family’s herd of 800 sheep. One of nine children and a third-generation member of one of the Aspen area’s most well-known families, Stapleton bridged Snowmass’s ranching and skiing eras.

Born in 1927 on his family’s Owl Creek ranch (the restored home is still there), he was one of Aspen Mountain’s earliest skiers. Although he performed hard ranch work in summer, slower winters allowed him to take a job in ticket sales with Aspen Skiing Company, one he held for 48 years.

In 1967, Stapleton sold 320 acres of his family’s ranch holdings around what’s now the Divide subdivision and Krabloonik sled-dog kennels—the former sheep pastures—to developer Bill Janss. A couple of years prior, Janss had hired some locals to scout the potential ski resort; the men, who often consulted Stapleton about the terrain and established a camp near his old sheepherder’s cabin, took to calling the area Sam’s Knob.

Hal Hartman Jr. in Hanging Valley in 1976.

Hal’s Hollow

Two generations of Snowmass men have spent their careers studying snow in its myriad beautiful and deadly forms. Powder was the purview of Hal Hartman Sr., one of the lead guides during the 1960s snowcat ski tours that previewed Snowmass before it opened. Hartman Sr. also helped scout the future ski area for developer Bill Janss and worked with Jim Snobble to design the trails. He was a natural fit to become Snowmass’s first ski patrol director, and the Hal’s Hollow run is named for him.

Hartman Sr. often brought along his son during ventures into Snowmass’s expert, out-of-bounds terrain like the Hanging Valley Wall. Hal Hartman Jr. followed in his father’s footsteps by joining the patrol. But then he took things a few steps further, gaining certification as a snow-safety expert and becoming an independent natural hazards analyst who specializes in avalanche forecasting and control, as well as an applied physicist. That scientific mindset made Hartman Jr. a driving force in opening the Hanging Valley Wall—Snowmass’s first swath of expert terrain—to the public in 1984.

Gwyn (now Knowlton) and George Gordon outside their on-mountain restaurant in 1980.

Gwyn’s High Alpine

What do flying, uphill skiing, and fine dining have in common? All passions of Gwyn Knowlton’s, they come together in a unique on-mountain restaurant.

Knowlton, namesake of Gwyn’s High Alpine, took over the midmountain restaurant with her then-husband, George Gordon, in 1979. A foodie, she conceived of a sit-down, fine-dining establishment alongside the more standard skiers’-fare cafeteria. The experiment was a hit. The next year, they expanded the dining room and wine cellar, and nearly 40 years later, four generations of families come in for Christmas breakfast.

After living at the restaurant the first season, the Gordons moved into town, commuting to work before the lifts opened on skis or snowmobile. Skinning up the nearly 2,500 vertical feet to the restaurant evolved into a favorite routine for Knowlton—who still skins to work two to three days a week—and a staff tradition.

In tribute to Knowlton’s competitive flying days (she was a top glider pilot), a sailplane hovers above diners in the restaurant, while on a sunny day, they might be treated to a flyover by Gordon in his 1947 Piper Super Cruiser.