Sojourner Salutes: A Tribute to Civic-Minded Locals

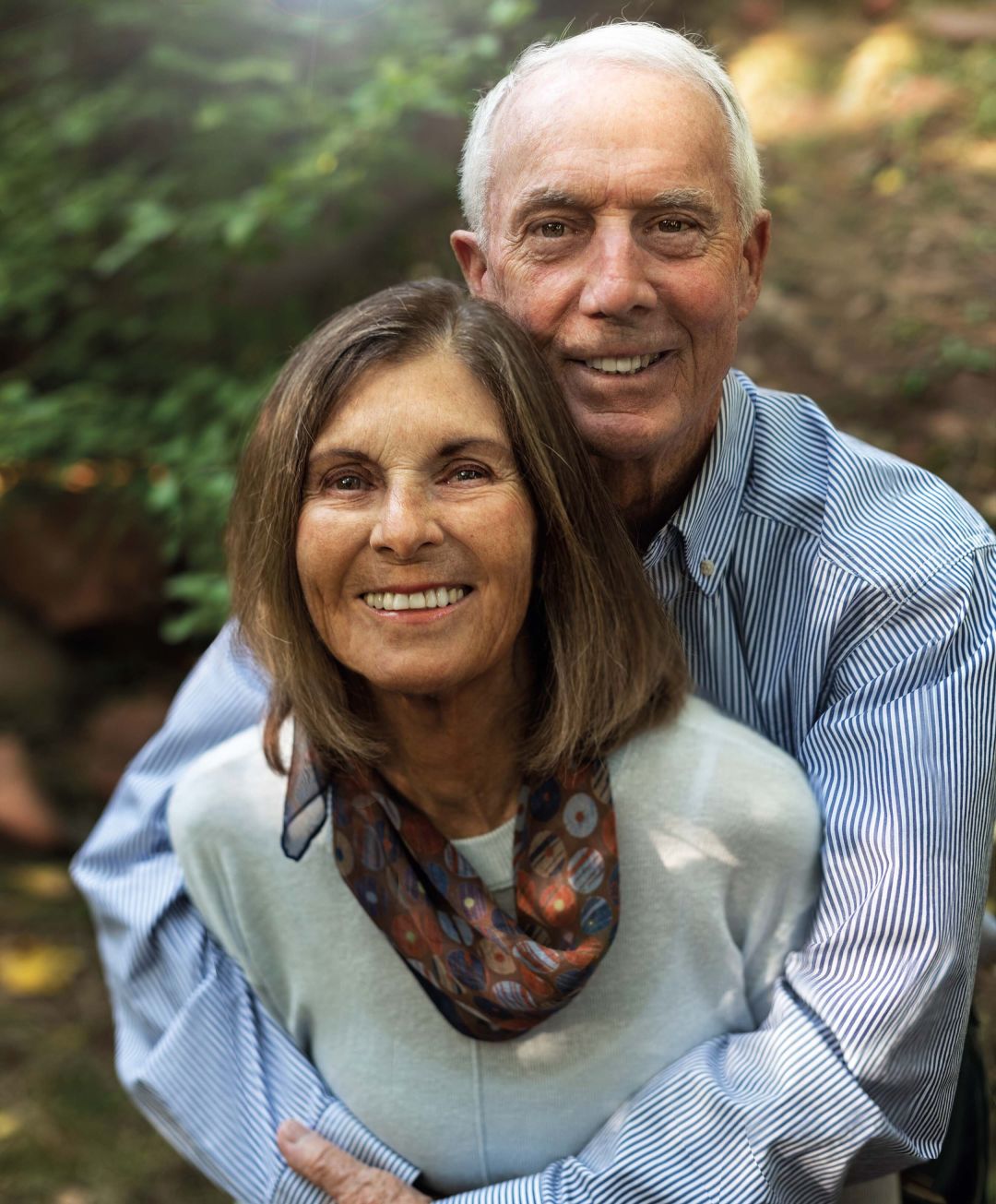

Carolyn & Bill Kane

This couple’s generosity helps make our community—and beyond—a better place.

In 1975, Aspen was in the throes of a community backlash over the wholesale turnover of entire blocks of its quaint downtown. Overwhelmed by a boom of newcomers in search of their own Shangri-la in the pristine Colorado mountains, the former mining town was bursting at the seams with a new kind of prospector looking to settle in a place that offered year-round recreation and culture. This new “white gold rush,” as it was known, wasn’t confined to skiing.

That was also the year that Bill and Carolyn Kane moved to the area. “We came at an extraordinary time in Aspen,” recalls Bill, who had just been hired as the Aspen-Pitkin County planning director. “There was a huge revolution in community values underway.” Entire blocks of Victorian miner housing had been razed to make way for mega projects like the North of Nell and Aspen Square. Subdivision regulations in Pitkin County had been enacted in 1973, he explains, “so you can imagine we had a pretty sharp divide between rural and urban folks. Everyone was involved in trying to frame a vision for the future of the community.” Ever the optimist in times of conflict, Bill chuckles. “It was a great time to be here.”

Later, Bill’s career in land use planning and design took him around the world via stints with Aspen-based Design Workshop and the Aspen Skiing Company, while Carolyn worked in the obstetrics department at Aspen Valley Hospital, delivering hundreds of babies over a 25-year career and serving on the board of Community Health Services and the Aspen Medical Foundation. Curious and adventurous, their extensive travels often included language programs where they honed their Spanish and French skills.

After three-plus decades in Aspen, the couple moved to Basalt in 2008. No stranger to public service, Bill served first as town manager, and then as mayor of Basalt—his attention laser-focused on community building in the midvalley. Long gone are the days when Basalt was a wayside in the road where you got cheap gas, he says. “People are moving to Basalt to put down roots. They want to contribute. They want their kids to get a great education. My focus has been promoting the development of permanent institutions.” Those institutions he’s referring to include TACAW, the Art Base, Basalt’s downtown renewal, and the open space collaboration the town consummated with Pitkin County Open Space and Eagle County. “I find it remarkable that you can travel between Carbondale and Basalt on the Rio Grande Trail and see minimal development. It’s just very gratifying. Preserving the natural environment isn’t a civic or cultural institution. It is, however, an important part of defining who you are as a community.”

While Bill pursued valleywide issues, Carolyn followed her passion for helping people. One of her long-term commitments is English in Action, where for several years she has tutored two students, one of whom recently received her citizenship. “English in Action is a very community-supportive nonprofit because it enables the people who reside here and, in many cases provide essential services, to attain the skills to communicate and the aspirations to grow in a community that is different than where they came from.” She feels similarly about the Basalt Library, another organization that has benefitted from her strong leadership and support. “We are so lucky to have good libraries throughout the valley. It’s important that each community has its own library that is available for anyone of any age. It’s a huge community value.”

“Their community service comes from a place of deep personal and professional motivation,” offers one of the Kanes’ many close friends. “Carolyn and Bill are a unique team. They bring rock-solid points of view to the table in a world in which reason and empathy are rare to find. Their motives for participating in their communities have always been about improving life for others.”

—Sarah Chase Shaw

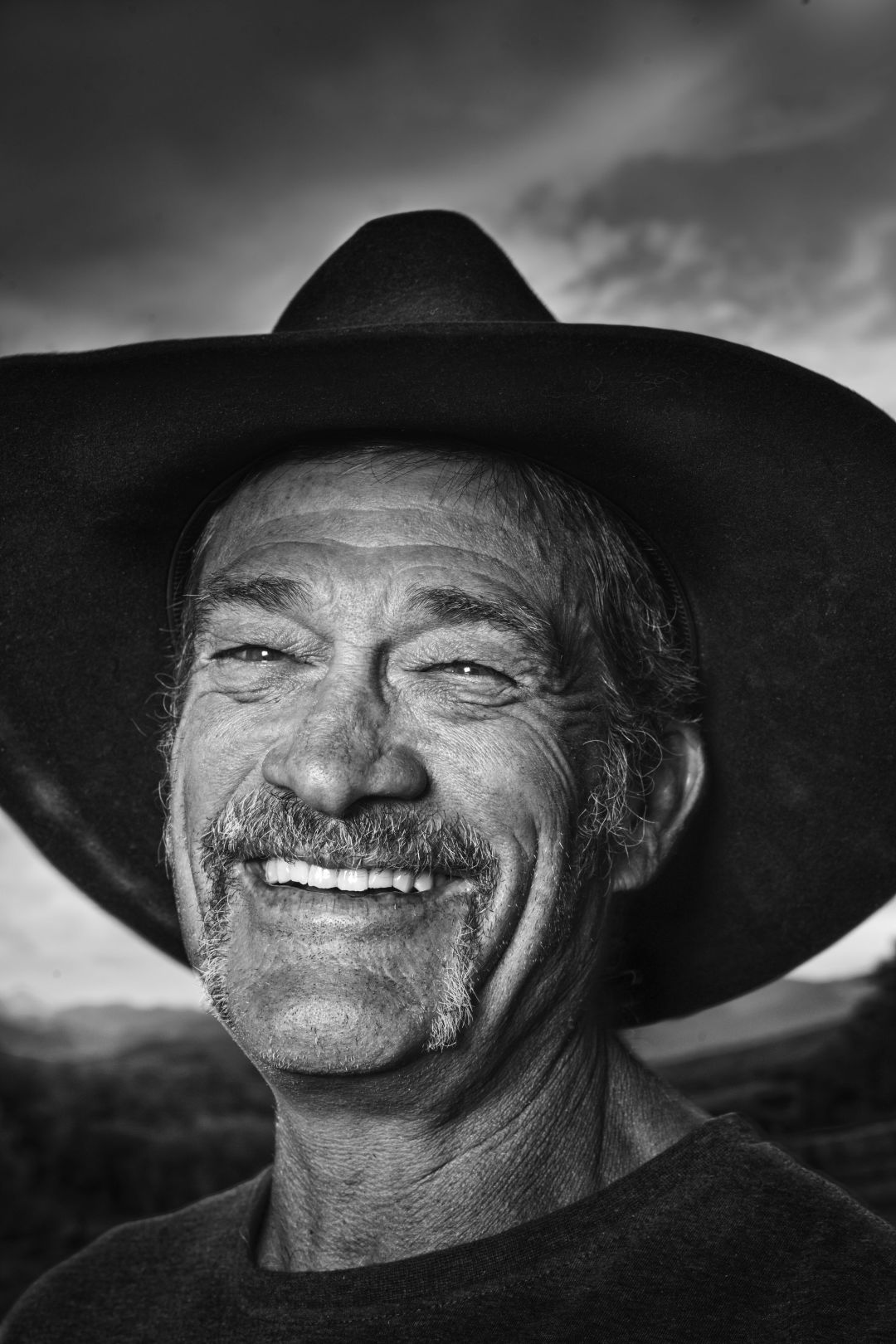

Johno McBride

This celebrated ski coach for both the Aspen Valley Ski and Snowboard Club and two national teams has positively impacted countless athletes.

Amid Aspen’s rich legacy of ski racing, it takes rare dedication to stand out among the generations of racers and coaches who have lived and worked here. John “Johno” McBride is one such local. As a celebrated ski coach for both the Aspen Valley Ski and Snowboard Club (AVSC) as well as two national teams, McBride has positively impacted countless athletes, from grade-schoolers to international stars like Bode Miller and Daron Rahlves. As tribute, he was inducted into the Colorado Snowsports Hall of Fame (with Lindsey Vonn and others) at a September 2024 ceremony in Vail.

McBride grew up on his family’s cattle ranch in Old Snowmass—one of three kids raised by parents Laurie and John McBride, former Sojourner Salutees known for their business acumen and philanthropy. Part of the younger McBride’s natural ease with coaching young Aspenites comes from his own experience as one. He joined the Aspen Valley Ski Club at age 7, skiing every day after school and racing locally. After a stint during high school on the US Ski Team’s development squad, McBride attended the University of Vermont, then returned to Aspen, where he first coached young skiers and the Aspen High hockey team.

Since then, McBride’s coaching career has had as many twists and turns as a tightly set slalom course. He’s served as head coach of the US men’s speed team three times, coached the Canadian Ski Team (including athletes at two Winter Games), worked with the US adaptive alpine team when it trained in Aspen, and coached several times for AVSC, most recently serving as alpine director through spring 2024. This winter, in addition to working on the family ranch, McBride will coach U12 kids at AVSC.

A common thread is McBride’s natural gift for engaging athletes, earning their trust, and inspiring them to achieve their best. Skiing great Bode Miller, who narrated a video played at the hall of fame induction, called McBride “a modern-day Pied Piper of skiing.” He’s not above doing anything it takes to support his athletes, either, whether driving cargo vans for the US Ski Team or cheering on his young charges at every AVSC race.

McBride says he developed his coaching philosophy by “watching and learning and listening.” When he was young, “I was fortunate to have had a couple of really good coaches and also some bad ones,” he adds. “But I never had the kind of mentorship where someone would ask me hard questions and put me in a position to apply myself at the level that I ask my athletes to apply themselves.”

One of the hardest parts of being a good coach, he notes, is understanding someone well enough to know when to push and when to back off. Fortunately for McBride, “I felt like I could connect with people pretty well and read them,” he says. For the national teams, McBride created unconventional dryland conditioning sessions, like bringing in skiers to camp at the family ranch and scale nearby 14,131-foot Capitol Peak. “I thought there might be a real benefit to taking people out of their element and pushing their boundaries,” he explains.

Turns out hurtling oneself down an icy slope at 80 miles per hour doesn’t necessarily translate to scrambling up exposed ridges with thousand-foot drop-offs. “It was eye-opening for them,” McBride says.

Whether working with an Olympic medalist or a kid in Aspen, McBride maintains a consistent approach. “I always try to be very honest with what I see and what I believe,” he says. Building a strong foundation with up-and-coming racers matters too. “The most important thing with young kids is that you have to create an environment where they want to come back the next day,” he adds. “If you do that well and it’s fun for them, there’s a good chance they’ll continue.”

Not only that, but it’s a great long-term strategy. Said McBride during his induction speech of the teams he coached: “We proved that you can be professional, you can work hard, [and] you can have a good time.… You can laugh at each other and laugh at yourself, and you can still kick ass.”—Cindy Hirschfeld

Rachel Richards

This local leader addressed Aspen’s most pressing issues and helped the community thrive.

Rachel Richards’ start in public life was, on the surface, unlikely. A young, divorced single mother living in Aspen Village, commuting to an upvalley job and trading childcare with another single mom, she seemed like a typical local worker bee just trying to get by. Except that she wasn’t.

Raised in Washington, DC, in a politically conscious family and attending Catholic school growing up, “the idea of community, helping others, doing what you can to plant vineyards that others can drink from, those things created my values,” says Richards.

Around 1987, she participated in a series of community forums at Colorado Mountain College called Hard Choices, where attendees discussed local issues such as growth, transportation, and childcare. The next year, having bought a deed-restricted Hunter Creek condo for $64,500 (and renting out a bedroom while she slept in the living room to help with expenses), she volunteered to help turn the city snow dump into a park (now John Denver Sanctuary), working into the evening to weed garden beds. She then joined Aspen’s Clean Air Advisory Board.

“I attribute a lot of my involvement to having a son and thinking about his future,” says Richards. “The air quality was his air quality; our environment is his environment. I’ve always been more future-generation-oriented in my thinking.” (Later, some would criticize Richards for remaining in public life when her son was arrested for taking part in a 1999 youth crime spree and sent to prison; she attributes his subsequent community-serving success in life to be partly due to her leading by example and not retreating under tough circumstances.)

Richards, whose day job distributing magazines and brochures throughout Aspen and Snowmass gave ample opportunities to hear from locals on what they cared about, was elected to Aspen City Council in spring 1991, during a time of debate and turmoil over fundamental local issues like growth and transportation. She served two four-year terms on the council and one two-year term as mayor. After being defeated for a second mayoral term, she won a council seat again in 2003, then four years later was elected to the Pitkin Board of County Commissioners, which she served on for 12 years before successfully running again for city council, finally retiring from public office in spring 2023.

Over 30 years of public service, Richards got a lot done. Crediting those who laid the groundwork and those who served with her, she nevertheless counts among her proudest achievements ones she specifically took initiative on—and that addressed Aspen’s most pressing issues. These include turning the Yellow Brick building into a childcare center; approving the Aspen Recreation Center and raising funds for it to house the Aspen Youth Center as amenities benefiting families; leading jurisdictions valleywide to create RFTA, the largest rural transit system in the country; and pushing multiple affordable housing projects, chief among them Burlingame Ranch. As mayor, Richards worked on the final annexation agreements for the 258-unit workforce housing project, which received enthusiastic voter approval under her watch and was the impetus for her 2003 city council run.

Richards’ insistence that Burlingame would be a worthwhile investment for families, especially those raising children, to become rooted in the community through home ownership (rather than mass dorm-style rental housing) resonated strongly with Steve Skadron, who served in Aspen public office from 2003 to 2019 (never on the same board as Richards) and kept that lesson in mind when he was dealing with Burlingame.

“Rachel is like a warrior,” says Skadron. “I value her tenacity and willingness to remain in the fight to preserve her best vision of Aspen. I think the community is better for it.”

But Richards’ vision was not exclusively focused on Aspen; she recognizes that Roaring Fork Valley and even rural Western Slope communities are inextricably connected on several issues. Throughout her service, Richards actively held seats at regional tables as a member of the Colorado Municipal League, Club 20, Colorado Counties Inc, and the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments, whose water quality and quantity commission she chaired for three years, leading water legislation efforts. “She has ideas and talks about them like a firehose, which I found energizing and motivating,” says Jacque Whitsitt, a former Basalt councilwoman and mayor who served with Richards on the RFTA board and at the Colorado Association of Ski Towns. “She also worked really hard to see all sides of the valley.”

Except during her mayoral term, Richards always worked other, public-facing jobs, including, during the pandemic, a challenging stint at City Market’s pharmacy. In semi-retirement, she nurtures hobbies like gardening, camping, and reading. But she can’t help staying involved, and this past summer she became very vocal in the renewed Entrance to Aspen debate. “I still don’t sleep well thinking about the things affecting our town,” she says, capping a passionate argument about the importance of getting valleywide transportation right, also for commuters and future generations.

Now, as Richards watches the evolution of the same issues that first drew her into public life, she notes that the community is facing a new set of hard choices.

“Aspen has been my garden,” she says. “And sometimes I see people pulling the garden out. We’ve harvested all the low-hanging fruit. I might just be a mosquito in the bedroom. But we need someone with backbone and a little vision.”

—Catherine Lutz